As an economist trained at a public university in Colombia, I grew up surrounded by talented people determined to overcome their circumstances. Today, when many of my classmates and I have achieved goals that once seemed unattainable, I recognize that our progress cannot be explained solely by innate abilities or economic resources, but by something less measurable: mutual support, companionship, friendships, and bonds of trust that sustained us through the most uncertain times.

In the midst of chaos, when we didn’t know what to do or how to solve difficulties, it was those human relationships that allowed us to overcome them. This experience leads me to question how economics has defined poverty and quality of life, and to what extent its indicators have overlooked what is most essential to social life: our connections with others.

Beyond income

For decades, academia and international organizations have focused the debate on indicators that reduce poverty to a monetary issue, as if an income threshold could fully explain human well-being. Not even the capabilities approach —proposed by Amartya Sen— can capture the complexity of life if real opportunities are restricted. When access to good education, decent employment, or credit is denied, capabilities are frustrated and poverty persists.

But there is something deeper that often goes unnoticed in these analyses: interpersonal relationships. As Silvia Congost pointed out in her talk The Secret of Relationships, a person’s quality of life does not depend solely on income, degrees, or achievements, but on the quality of their relationships —that is what gives life meaning. Measuring poverty solely by income or material deprivation is, at its core, a way of ignoring what makes us human.

‘Ubuntu’: “I am because we are”

The African philosophy of ubuntu, popularized by Desmond Tutu and Nelson Mandela, offers a powerful alternative to development models centered on the individual. “I am because we are” sums up a vision of well-being based on interdependence. From this perspective, poverty is not measured by what is missing in one’s pocket, but by what has been broken in the social fabric that binds people together.

This relational poverty does not refer to material deprivation but to the absence of stable social bonds, interpersonal trust, and recognition. It is a form of emotional and civic impoverishment that manifests as isolation, fear, and collective indifference. Axel Honneth expressed it clearly: the struggle for recognition is as important as the struggle for resources. A society in which people lack recognition and voice is impoverished, even if its GDP grows.

Here, ubuntu offers a moral compass: no one can fully realize themselves in isolation. Human life flourishes in community, where one person’s well-being depends on that of others. When the “we” disintegrates, the “I” is also impoverished.

Recent studies reinforce this idea. The Spirit Level, by Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett, shows that more unequal societies are not only less healthy but also more distrustful. The World Happiness Report 2024 identifies social relationships as the main determinant of subjective well-being, even above income. And the OECD’s Better Life Index includes “social relationships” as an essential dimension of well-being, although in Latin America they have yet to become central to public policy.

The challenge of the virtual

To this relational vision, we must add a contemporary challenge: virtuality.

No matter how useful social media and artificial intelligences may be, no technology can replace human presence. No algorithm can replicate the experience of looking into someone’s eyes, sharing silences, feeling real empathy, or offering help that is consistent with human emotion and morality. No AI can equal the connections that human neurons have built over millions of years of evolution.

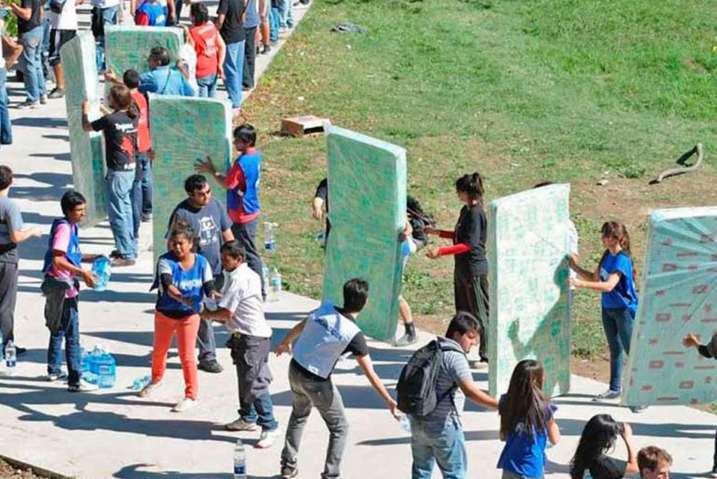

Latin America faces a double poverty: material and relational. The first cannot be fought only through transfers, subsidies, or social programs —as is often said in many political speeches— but by creating stable, long-term income opportunities within a mandatory social security structure. The second, more invisible one, is reflected in distrust and the fragmentation of community ties.

According to the Latinobarómetro 2024, only 15.3% of Latin Americans trust their fellow citizens. This means the continent is one where inequality separates not only incomes but also emotions. Violence, unemployment, and urban precariousness have weakened cooperation. In many cities, fear replaces dialogue, and individual survival has taken the place of collective well-being.

Social policies, while necessary, tend to focus more on income than on relationships —not even the Multidimensional Poverty Index escapes this vision. It measures households, not communities; it counts subsidies, not trust. That is why many programs relieve hunger but not despair. It is not enough to transfer resources if people lack ties, networks, or spaces where they can exercise citizenship.

Rethinking the measurement of well-being

If what is not measured does not exist, it is urgent to start measuring the bonds that sustain us: incorporating indicators of social capital, community participation, and interpersonal trust would allow for a better understanding of the dynamics of well-being. The United Kingdom and New Zealand already include variables on personal relationships and social cohesion in their budgets. In Latin America, ECLAC has made progress in measuring social cohesion, but it is still necessary to integrate these indicators into the core of anti-poverty policies.

Measuring relational poverty does not mean abandoning economic indicators but complementing them. Family networks, neighborhood cooperation, and community spaces cushion crises and strengthen social resilience. A family may rise out of monetary poverty, but if it lives surrounded by distrust or violence, it remains vulnerable.

An ethical and political invitation

A society impoverished in relationships risks degrading its democracy, so relational poverty is not just a statistical problem but also a moral and political one. Distrust destroys participation, cooperation, and the sense of community.

Rethinking poverty as a relational phenomenon is to return to a simple truth: well-being cannot be achieved in isolation. People thrive when they can trust, belong, and feel valued by others.

If Latin America aspires to truly human development, it must go beyond income and consumption. A region may reduce its poverty indicators, but it will remain poor as long as it stays fragmented. True wealth —individual and collective— begins when we recognize ourselves in one another again.

If I end this text as I began it, education at any level is a key element not only in building capacities and identities but also in building relationships of trust —not in fostering competition that fragments community ties.

*Machine translation, proofread by Ricardo Aceves.