Increasingly, in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), artificial intelligence (AI) is being used in everyday decision-making processes that affect millions of people: scholarship selection, social subsidies, alerts from social services, biometric identification, and even guidance for victims of violence.

However, as highlighted by the Regional Human Development Report 2025, AI is consolidating in a region with persistent inequalities, and the data that feed these systems inevitably reflect the biases embedded in society. If algorithms learn from these realities, gender bias stops being a laboratory flaw and becomes a development problem: it can exclude those least represented in records, such as poor, indigenous, migrant, or rural women, further eroding institutional trust.

Yet the same technology that can deepen inequalities can also protect, inform, and create opportunities, especially for traditionally excluded groups. The challenge is to reduce this bias and implement verifiable controls that prioritize equity to expand rights, improve policy targeting, and foster more inclusive growth.

A “technical” problem that is already a development issue

One of the main uses of artificial intelligence is identifying patterns in large volumes of data to optimize decisions. However, models that “average” diverse populations can disadvantage underrepresented groups and reproduce historical patterns of discrimination. In social protection programs, for example, several LAC countries have incorporated automated models to classify individuals and allocate benefits, but scoring systems can perpetuate exclusion if they rely on data where women or other groups are not equitably represented.

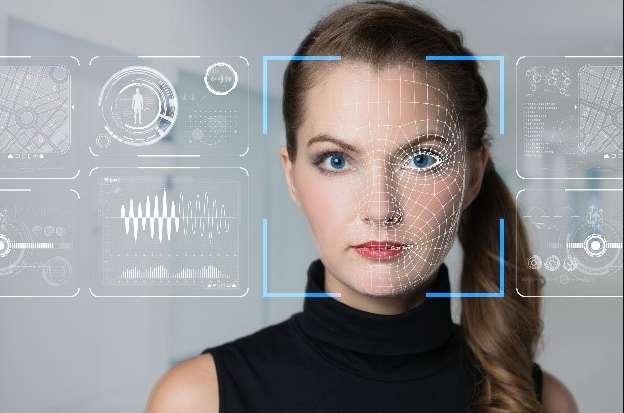

Gender bias appears in specific decisions, and public safety provides an equally illustrative counterpoint. The region has rapidly adopted biometric and facial recognition technologies, yet studies show that false positives disproportionately affect women, particularly racialized women. These identification errors compromise freedoms, may trigger unjust detentions, and amplify inequalities.

Similarly, when hiring algorithms replicate male-dominated work histories, or when credit is granted via models that penalize female trajectories according to traditional banking criteria, opportunities for women are reduced, productivity is lost, and entrepreneurship is limited. The region cannot afford technologies that exclude female talent from already segmented markets.

Investing in representative data and strengthening regulatory frameworks for AI use, including equity metrics and accountability mechanisms, are key steps toward using this technology responsibly and inclusively. In this way, artificial intelligence can become an opportunity not only to improve decision-making efficiency but also to broaden the base of innovation beneficiaries, accelerate digital adoption, and promote labor and financial inclusion.

It is also important to consider the symbolic dimension: the default feminization of virtual assistants or chatbots, through their names, voices, and avatars, reproduces hierarchies. This may be justified in specific services, but as a norm, it reinforces stereotypes about the role of women in society. Interface design, increasingly used to enhance public service delivery, is also an element of public policy.

Female leadership: From “outliers” to designers

Principles of non-discrimination, transparency, and human oversight are already included in the strategies and frameworks of several countries in the region. The challenge is to translate them into verifiable controls: documenting the demographic composition of data; evaluating performance by subgroups (women by age, origin, migration status, or rurality); monitoring outcomes after system deployment; and requiring mandatory independent audits for high-impact systems (such as those used in social protection, health, justice, and security). With these controls, AI becomes auditable and governable.

Due to historical exclusions and low visibility in formal data, systems tend to classify women as “outliers,” a term in statistics referring to an atypical value—an observation numerically distant from the rest of the data. From a strictly statistical perspective, datasets with outliers can lead to erroneous conclusions and are generally avoided. However, this does not always apply in more nuanced contexts, such as credit applications, job openings, or social programs, where women’s characteristics may differ from men’s but should not be grounds for exclusion from selection processes.

Women in the region are not only users of AI but also leaders in creating solutions: feminist frameworks for AI development, open tools to detect stereotypes in language models, and initiatives incorporating a gender perspective into platform work. Placing women at the center—as designers, auditors, regulators, and users—improves the technical quality of systems and accelerates their social acceptance. This is also a policy of innovation.

Ultimately, reducing gender bias multiplies returns: more precise and legitimate social policies; security compatible with rights; more inclusive and productive labor and financial markets; and greater trust in institutions capable of governing complex technologies. This translates into human development: more real capabilities—health, education, participation, decent work—and greater agency to influence one’s own life and environment.

AI is not neutral, but it can be fair. To achieve this, Latin America and the Caribbean must embrace a minimum standard already within reach: representative and documented data, equity metrics by subgroups, independent audits, and avenues for redress when harm occurs. Reducing gender bias not only opens opportunities for women but also drives development for the entire region.

This article is based on the findings of the Regional Human Development Report 2025, titled “Under Pressure: Recalibrating the Future of Development”, produced by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) in Latin America and the Caribbean.