In a debate about the recent closure of the Ministry of Culture and Heritage in Ecuador, one of the participants defined the creative process as a collective act of care; behind every talent there is a community that sustains and embraces it. Thus, this “collective care” is built from processes, spaces, and public policies; in other words, through an ecosystem that nurtures these talents so they may flourish.

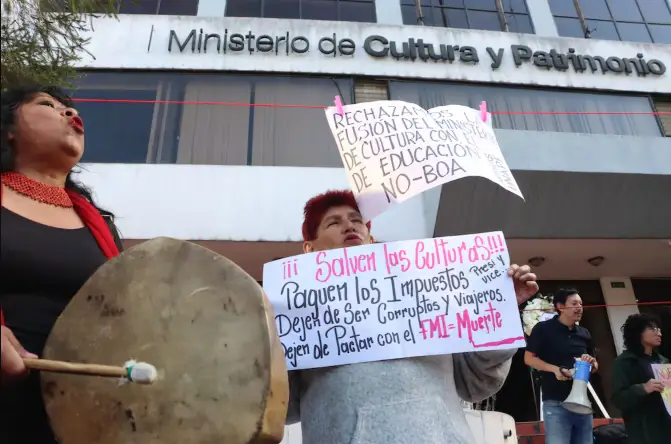

Does the recent closure of Ecuador’s Ministry of Culture and Heritage imply the disappearance of an institution that sustains processes, fosters spaces, and drives public policies? Without nuance, the answer is yes. The government of Daniel Noboa, as part of its state optimization policies, identified, in its own view, that the Ministry did not add value to society beyond its bureaucratic role. It merged it with the Ministry of Education, gave it a minor role, and confined it to an administrative dependency that further limits its already meager actions.

This liquidation returned Ecuadorian cultural institutions to a stage similar to that of the 2000s. Until the arrival of Rafael Correa, state cultural policy held a subsidiary rank, complemented by adjunct organizations such as the National Council of Culture and other “autonomous” ones like the Benjamín Carrión Ecuadorian House of Culture. The closure of the Ministry was the result both of a political stance —which Javier Milei described on his X account as a “neighborhood phenomenon” and an example that his radical policy of downsizing the state was being replicated in the region— and of the exhaustion of the model that sustained it.

According to anthropologist and cultural manager Fabián Saltos, Ministries of Culture in the region were born out of a French-inspired logic, understood as central public institutions that organize and guide the creative act. But under the nationalist populist logic of the Ecuadorian government from 2007 to 2017, which created the Ministry, the bureaucratic structure defined the scope of public policy itself. That is, the important thing was to have the Ministry; the rest would follow either by default or through the synergy of social and political events.

Under these parameters, the institution was a boat that, without a clear course, managed to survive for nearly twenty years through the continuous economic storms of a country whose heavy fiscal deficit periodically forces it to review the list of “unnecessary” institutions to be cut down outright, or under the blade of a chainsaw. There is a popular saying in Ecuador that goes: “a cada chancho, le llega su hornado,” which translates as “every pig gets its roast,” and that is what happened to the Ministry of Culture and Heritage. The most reactionary groups demanded its death on the very day of its creation, but many years later it was finally Noboa’s government that downgraded it to a Vice Ministry, once again dependent on the same Ministry of Education from which it had originally separated, and with an even leaner budget.

Can we say that the reason for its institutional demotion is the result of a particular political vision of the government in power? The answer is not that simple, and fiscal adjustment is not the only reason. Responsibilities are shared. In a country overwhelmed by criminal violence and the tearing of the social fabric, the institution never exercised nor understood its strategic role. While organized crime looms over every aspect of daily life, the Ministry of Culture should have had a vital role in public security, on the same level as Defense, Interior, or Government; but that never happened.

From its creation, the institution was a hostage of particular interests that, depending on their proximity to power, manipulated and influenced without any vision beyond the short term. Expenditures were made for producing an album for the popular singer of the moment, equivalent to the annual budget of a local museum. Moreover, the political regime that created it, with its compulsive indebtedness model that sustained a false sense of well-being, used it as a tool to keep the “hyenas” circling their prey sufficiently satisfied to continue supporting the “project.” Its creation had a circumstantial, more than symbolic, background. In other words, the institution did not arise from a state political response to support talent and artistic creation, but to help sustain the propagandistic narrative of a “new country.” Under that logic, the latter was subordinate to the former.

Furthermore, the new Ministry functioned as a governing body on paper, but the course of economic hardships turned it into a mere administrator. It administered late, poorly, or never, adjunct bodies such as museums, institutes, or orchestras, always short of funds and of real transformative capacity.

Thirdly, the competitive funds it managed through related institutes gradually became the most visible part of the skeletal administration of the day. It was a vertical, hierarchical institution that was slow to adapt to the rapid changes inherent to cultural creation and its managers, whom it often disdained.

Finally, it had no real territorial presence and could not establish itself as an alternative to “independent” cultural institutions of local origin with public financing, which, despite their decline and political clientelism, still survive.

The disappearance of this institution has gone largely unnoticed, but it may leave important lessons for the region. An institution that develops its work in the realm of creativity must know how to adapt its administrative model to the logic of artistic creation and its industries; its primary role must be that of triggering conceptual processes that, while ensuring the material well-being of creators, contribute to the creation of new narratives and the demystification of outdated traditions.

Finally, its presence must be active at the territorial and local level in order to understand that, more than a social institution, it is a strategic security body. Above all, it must understand its role in the collective care of present and future talents.

*Machine translation, proofread by Ricardo Aceves.