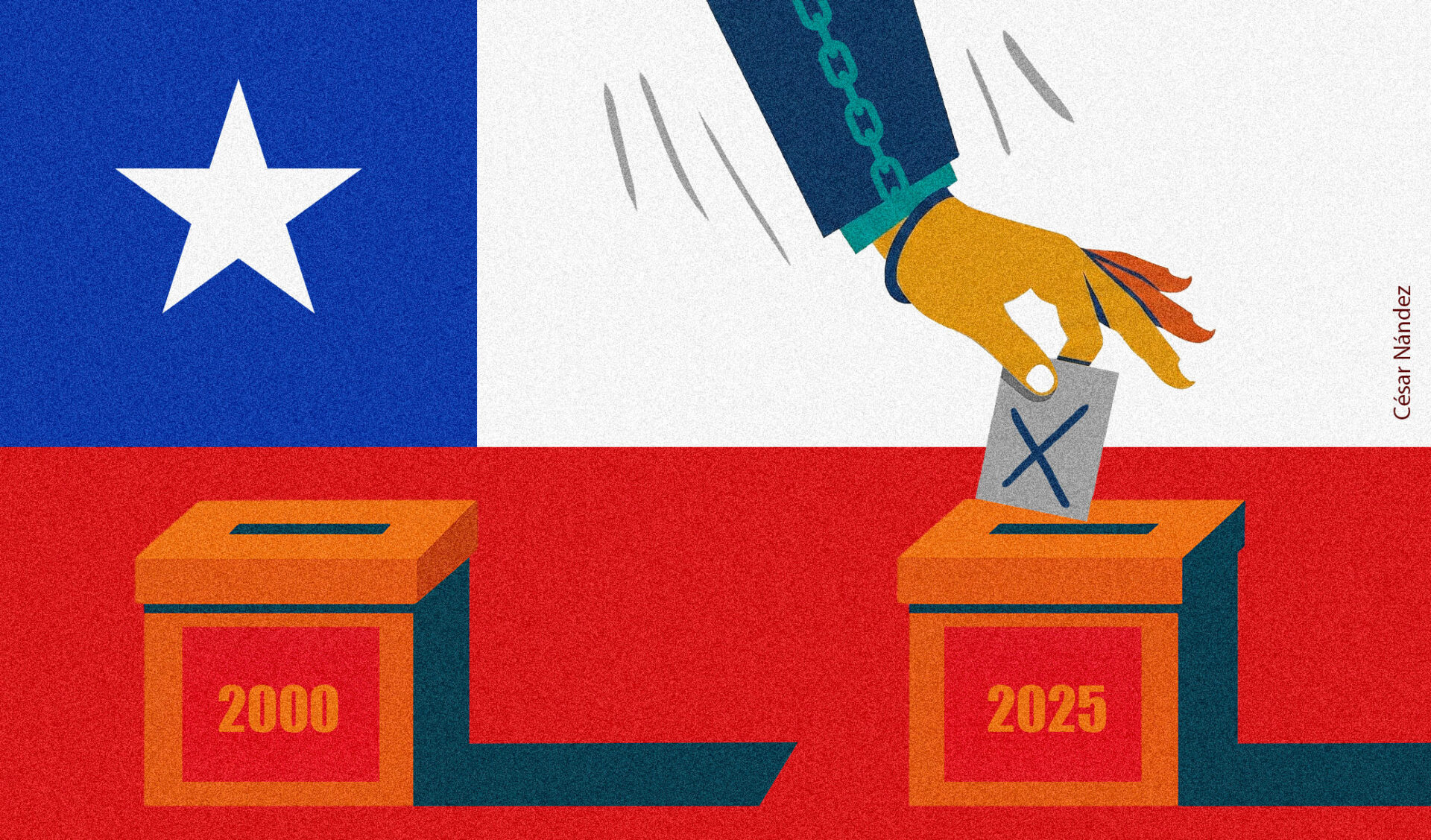

Next January marks twenty-six years since an unprecedented electoral outcome in Chile’s post-1989 democratic era.

It was the end of the term of center-left president Eduardo Frei Ruiz-Tagle. The electoral landscape was not promising. Unemployment had reached 11%, growth was flat, social conflict and perceptions of insecurity were rising, and disapproval of the government stood at 45% against only 28% approval.

The continuity of the ruling coalition was in doubt. When a governing party’s presidential candidate carries the weight of widespread dissatisfaction with the outgoing administration, holding on to power is usually unlikely.

Yet the 2000 presidential elections contradicted that trend. Despite a challenging electoral environment, Ricardo Lagos, the candidate of the incumbent coalition, managed to win the runoff by barely three percentage points over Joaquín Lavín, the right-wing coalition’s standard-bearer.

Since the return to democracy, this was the only time the ruling party held onto power despite majority disapproval of the outgoing president. Later attempts failed. In the 2013 and 2021 elections, the governing center-right’s efforts to retain power collapsed under the insurmountable burden of public frustration with President Sebastián Piñera. Meanwhile, in the 2017 elections, the center-left also struggled unsuccessfully against high rejection of Michelle Bachelet’s administration.

Reasons behind the unprecedented government victory in 2000

Although President Frei Ruiz-Tagle’s weak performance strengthened the opposition’s prospects, the right’s vote total was not enough. In 2000—just a decade after the transition and with the weight of authoritarian enclaves left by the dictatorship— the possibility of a right-wing victory was viewed by many as a serious threat to the continuity of Chile’s democratic regime.

Joaquín Lavín and key right-wing figures had undeniable ties to the Pinochet dictatorship. In the imagination of decisive segments of the electorate, a right-wing government raised concerns about democratic stability. The failures of Frei’s administration boosted the opposition’s electoral appeal, even helping them achieve their highest vote share ever. But they did not convince the majority of pro-democracy voters that they were a credible governing alternative.

Chile’s 2025 presidential elections: on the same axis as 2000?

There is an important similarity between the 2000 runoff and the one to be held next December 14. The governing coalition’s presidential candidate—Communist Party member and former Labor Minister Jeanette Jara—enters the race weighed down by a strongly negative public assessment of President Gabriel Boric’s administration.

The September-October survey by the Centro de Estudios Públicos (CEP) reports Boric’s disapproval at 62%. Only 28% approve of his performance. In Chile, as in Latin America, such numbers consistently foreshadow an unfavorable electoral outcome for the incumbent.

But on the other side stands the controversial figure of José Manuel Kast, leader of the Republican Party. In 1998, Kast supported Pinochet’s continuation in power. He chaired the Political Network for Values, often considered extreme. He has defended the dictatorship’s economic legacy and stated in the 2017 elections that the General would vote for him if he were alive. Kast and the Republicans come from the far-right end of the ideological spectrum and have no national-level executive experience.

The 2024 Latinobarómetro report found that 61% of Chileans support democracy. The key question remains: Would a Kast government represent a threat to the continuity of democracy in Chile?

Indeed, the 2025 runoff recreates, in some ways, the dynamic of the 2000 race: a left-wing governing coalition with poor public approval seeks to retain power against a (far-)right actor whose democratic commitment is questioned by large portions of the electorate.

Will history repeat itself?

The precedent of 2000 is important but not necessarily decisive. One must remember that Argentina’s 2023 presidential elections also pitted a weakened left-leaning incumbent coalition (Unión por la Patria) against a far-right party with no governing experience (La Libertad Avanza), which nonetheless won the overwhelming support of voters.

Elections featuring these kinds of opponents do not necessarily lead to the same outcome. The correct starting point should be another question: What determines whether a contest between a poorly evaluated left-wing incumbent and a right-wing challenger with limited credibility tilts toward one or the other?

The lens through which voters approach the polls

Voter support under these circumstances depends on how they perceive the broader context. If conditions are perceived as only moderately unfavorable, they may lean toward continuity. But if the situation is perceived as critical, voters are likely to set aside their reservations and back the challenger.

The latest CEP survey offers clues about the mindset Chileans will bring to the polls on December 14.

Eighty-four percent describe the country’s situation as bad or average. Eighty percent believe Chile is stagnant or in decline. Eighty-nine percent rate the political situation as average, bad, or very bad. Sixty-four percent say democracy is functioning poorly or mediocrely, compared to 33% who say it works well or very well. Forty-eight percent agree that under some circumstances an authoritarian regime may be preferable—or that it makes no difference. Meanwhile, 47% say democracy is always preferable.

Other indicators

Other data show how the balance may tip. Candidate image matters. Kast enters the election with 38% favorable and 39% unfavorable views—a dramatic improvement compared to his 2021 defeat, when only 16% viewed him positively and 61% negatively. His opponent Jeanette Jara holds 32% positive and 44% negative ratings.

In the first round, Jara received 26.8% of the vote versus Kast’s 23.9%. The populist Franco Parisi of the Partido de la Gente finished third with nearly 20%. Parisi has urged voters to cast null ballots, but polls show that 49% of his supporters would back Kast and only 16% would support Jara.

Two additional first-round candidates—the libertarian Johannes Kaiser and the traditional right’s Evelyn Matthei—received 14% and 12.5%, respectively. Both, ideologically close to Kast’s Republican Party, immediately backed him in the runoff.

Although the Republicans hold the largest share of seats in the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate, they lack the majorities needed to pass reforms that could subtly alter the political system. If they form a government, congressional dynamics would force Kast to negotiate with other parties.

Finally, Kast’s campaign has focused on the three issues citizens prioritize most—order, migration control, and the economy—areas where the incumbent government has underperformed.

It would be surprising if the 2000 results were repeated. It seems more reasonable to expect that most voters will set aside their reservations about a Kast presidency and elect him as Chile’s next leader. Sometimes history repeats itself, but at other times it reinvents itself.

*Machine translation, proofread by Ricardo Aceves.