The risks posed by global warming have become an inevitable focus of the financial market. Increasingly, investment funds are aligning their decisions with environmental, social, and governance criteria, also known as ESG; companies and governments are issuing “green” bonds (intended to finance environmentally positive investments); ESG rating agencies are proliferating, and traditional credit rating agencies are incorporating ESG factors into their methodologies. Environmental issues are an urgent topic on the international agenda, and the financial system, through what is known as “green finance,” is one of its mechanisms of projection.

A consequence of the market’s adaptation to climate issues is the inclusion of government credibility in the evaluation. In the context of financial globalization, “political risk” is a significant variable for investment decisions. In liberal democracies, right-wing governments tend to enjoy greater credibility in the eyes of the market due to their emphasis on monetary stability in economic management. Left-wing governments, on the other hand, are often met with investor skepticism as they prioritize social welfare, which is sometimes at the expense of rising inflation. Historically, this translates into a more pronounced pattern of political risk when a left-wing government is in power.

New Right

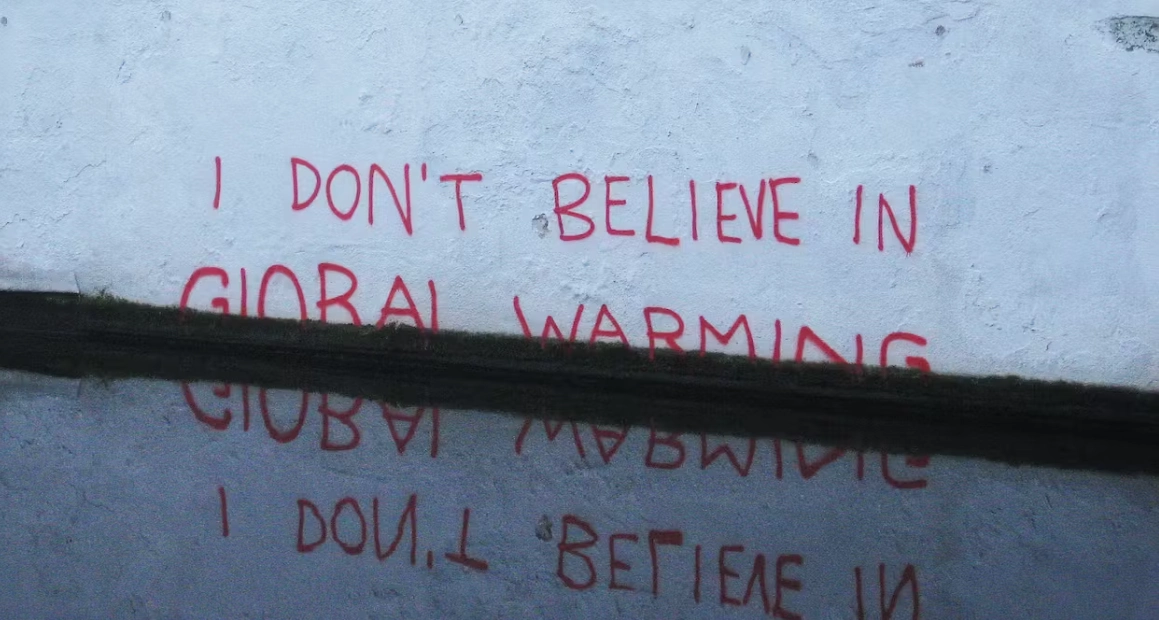

However, political transformations in the 21st century, amid the climate and environmental crisis, should flexibilize this pattern. A “new right” is emerging worldwide, often labeled as “populist,” “extremist,” or “radical.” One characteristic of these agents, which has overshadowed the space of traditional right-wing parties, is scientific denialism, in general, and climate denialism, in particular.

As electoral polarization translates into a contest between left and right, it tends to become a vector of even graver political risks than those associated with the left. With the progressive realization of climate risks for the market, financial losses related to a government representing this “new” right will become increasingly tangible.

Claire Parfitt and Gareth Bryant, professors at the University of Sydney, study the damages caused by climate denialism of the conservatives in the United States. The populist advance of the Republican Party, epitomized by former President Donald Trump, has led to accusations of “politicizing finance” by right-wing congressmen and demands for and imposition of denialist regulatory frameworks. In Florida, for example, Republican Governor Ron DeSantis forced the state pension fund to eliminate ESG considerations from its investment decisions. Bills against green finance are proliferating throughout the country. In 2022 alone, nineteen state and Republican attorneys general accused BlackRock, the world’s largest asset manager, of sacrificing profitability for climate activism. According to The New York Times, climate damage will be the most enduring and profound legacy of the Trump administration.

Passing the Ball

The reality is not much different in Brazil. For two decades (1994-2014), polarization in presidential elections occurred between the “moderate” PT and PSDB, benefiting the country’s democratic maturing. Nevertheless, the traditional right collapsed in the second decade of the 21st century, ceding its hegemony on the political spectrum to populist groups rallying around Bolsonarism.

In an article published in the journal Environmental Conservation, Silva and Fearnside list various initiatives by the government of Jair Bolsonaro to drive environmental devastation. Government actions have included gutting and cutting funding for public agencies responsible for environmental protection (such as Ibama and Funai), authorizing mining on indigenous lands, and a series of measures, including presidential decrees, that have facilitated deforestation and hindered environmental monitoring. During a ministerial meeting in May 2020, then-Minister of the Environment Ricardo Salles famously proposed taking advantage of Brazilian distraction during the COVID-19 pandemic to pass laws. In September 2022, the ashes of the Amazon rainforest darkened the city of São Paulo.

It is likely that examples of climate risks posed by this “new right” will become even more abundant if more of its representatives come to power. In France, the far right achieved a record vote in 2022, with Marine Le Pen defeated by Emmanuel Macron. In Spain, a rising populist party Vox’s parliament member even claimed that global warming could reduce deaths from cold. Meanwhile, Germany witnesses the progressive electoral advancement of the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD), which includes several climate deniers among its members. In the global South, 2023 could also be a turning point in Argentina, where right-wing populist Javier Milei led the presidential primaries. For Milei, global warming is nothing more than “a lie of socialism.”

Loss of Credibility

While the level of delusion and conspiracy varies case by case, the argumentative strategy involves linking the economic crisis to measures aimed at mitigating the climate crisis, which is nothing more than a fantasy invented by the establishment. The environmental issue, it is worth emphasizing, is just one facet of right-wing populist denialism. In any case, it may be the one with the most devastating consequences in the medium term, possibly when a point of no return has already been reached.

As a global phenomenon, the cost of this new right-wing denial tends to be assessed by the financial market as the realization of climate-related risks becomes evident in investments worldwide. On one hand, this signifies a relative loss of credibility for the right in the eyes of the market. On the other hand, this reorganization of political risk parameters can serve as a source of pressure for the radical right to moderate its environmental agenda in order to achieve desired electoral outcomes. In other words, this process could have a positive effect on transitioning to a globally low-carbon economy.

However, as long as right-wing saboteurs remain strong in electoral disputes, the political risk they catalyze will remain far from any solution to contain them, especially given the conflicting interests of investors operating in the global financial circuit. Without a responsible right-wing that can once again consolidate its position on the party spectrum, achieving the goals set by the Paris Agreement and the UN Sustainable Development Goals will be a challenge. Understanding the right-wing crisis as a relevant component of the climate crisis is therefore an essential requirement to address the environmental problem.

Pedro Lange Machado is a PhD candidate in Political Science at IESP-UERJ and a visiting researcher at Freie Universität Berlin. Contact: pedrolangenm@iesp.uerj.br

*Translated by Ricardo Aceves from the original in Spanish.