The headlines of the leading media almost in unison state that last Sunday’s elections in Colombia were a major setback for President Gustavo Petro, a sort of referendum against his administration. Although this reading is not utterly wrong, it shows the predominance of interpretations characterized by an excessively “national” vision and an urban — even Bogotá — bias of Colombian politics.

The analysis of this type of election in Colombia requires understanding the strong contradiction between national electoral politics and regional and local politics. In each country, local and regional elections are usually marked by issues specific to these territorial contexts. At the same time, political parties often articulate politics at different levels — for example, through party identities-giving “national” overtones even to more local disputes.

In Colombia, by contrast, there is a strong disconnection between parties at the national and regional/municipal levels. Most of them are no more than national confederations of politicians with strong regional political machines, which are minimally articulated, for example, in the Congress of the Republic, but allow regional leaders to manage politics in their territories with remarkable autonomy. By their nature, these parties are very successful in subnational elections in Colombia.

Other parties and movements with clear national programmatic profiles are very competitive in national elections — as is the recent case of Gustavo Petro’s Historic Pact or former president Álvaro Uribe’s Democratic Center, — but have less local presence (capillarity) and are notably weaker at the subnational level. These usually try, unsuccessfully, to force disputes over national agendas in local and regional elections.

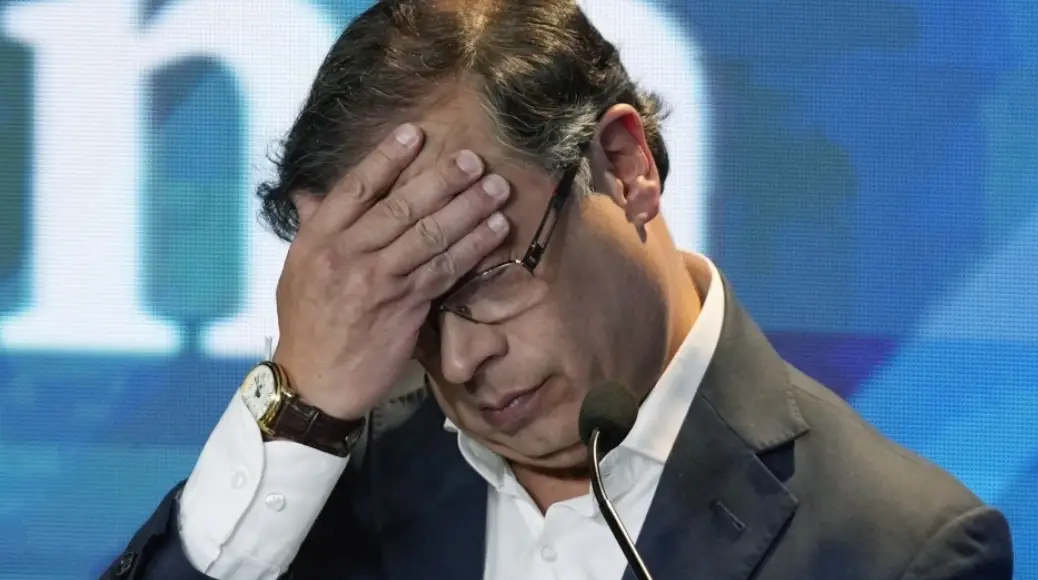

Petro, as on previous occasions Uribe, tried to nationalize local electoral disputes last Sunday, a very risky bet in a context where the local is not a function of the national. This happened especially in Bogotá: fomenting the conflict over the city’s subway with the district government was an attempt to boost the candidacy of Gustavo Bolívar of the Historic Pact (PH). Evidently, by barely obtaining third place, Petro was defeated in a fight that was almost unwinnable and perfectly avoidable. Thus, he laid the foundations of his own defeat.

However, it would be a mistake to think that this defeat was only a “referendum” on the government. Sure, there is a significant number of voters disaffected with the government who voted against “Petro’s candidate” in Bogotá and elsewhere in the country. But, just as the victory of Lucho Garzón in 2003 or Samuel Moreno in 2007 was not just a “referendum” against Uribe’s policies, or the election of Gustavo Petro as mayor did not mean the rejection of the Santos government in 2011, just as it happened with Claudia López and Iván Duque in 2019, the results in regional and local elections in Colombia are not exclusively the product of the growing disapproval of Petro’s government.

This is even clearer when we analyze the results in other major cities, where opposition mayors and governors were elected, even in regions where Petro had excellent results in the presidential elections. In Cali, Alejandro Eder managed to capitalize on the strong rejection of the current mayor, achieving a resounding victory against an opponent that was effectively presented as “continuity”. Although Eder is critical of the national government, he avoided by all means the nationalization of the local debate in a city where the central government maintains reasonably high levels of popularity.

At the departmental level, Dilian Francisca Toro, governor-elect of Valle del Cauca and who has controlled the department since 2016, won the governorship and won the election of a significant number of like-minded mayors thanks to effective political organization. With ambivalent positions vis-à-vis the national government, he managed to control the debate agenda, erasing any vestige of national politics that would make the Historic Pact a competitive force. The president’s coalition, after having sounded out some first-level names for the position, decided to launch a candidate with no real capacity to compete.

In Barranquilla, Alex Char won his third election with a resounding 73%, a reflection of a strong local political machine that is hegemonic in this region and has controlled the mayoralty of this city since 2008. Even in a scenario where the national government had better approval ratings than it has, it would be highly unlikely that a like-minded candidate would win in this city.

The victory of Federico Gutierrez (Fico) in Medellín and of Andrés Rendón Cardona, Uribist candidate for the governorship of Antioquia, may reflect, more than in the other cases, a nationalized dispute in territories structurally hostile to Petrism. Fico, after coming third in the 2022 presidential elections in Colombia, will probably use a new term as mayor of the country’s second city to prepare his return to national politics. However, the overwhelming result (73% of the vote) mainly represents a rejection of Daniel Quintero’s mayoralty. While the latter is a Petro ally, the low support for the mayor’s candidate last Sunday (second, with just 10% of the vote) reflects more the fact that Quintero is the mayor of Medellín with the highest disapproval in recent years.

Petro’s response to the poor results of the Historic Pact and its allies was to claim victories in a (somewhat inexplicable) number of governorships. Considering those that can be considered successes of the PH and allied forces, neither can these be interpreted as the result of the electorate’s support for his policies. The election of a Historic Pact governor in Nariño occurs in a department where the election of leftist governors (e.g., Antonio Navarro and Camilo Romero) is not a novelty. Citizen Force, an allied political group, maintained control of departmental power in Magdalena, more as a reflection of the consolidation of this political organization of the now ex-governor Carlos Caicedo.

At the same time, PH’s increased number of councilpersons (642 out of 12,000) and departmental deputies (38 out of 418), numbers that are yet to be determined with certainty, is a more inertial growth of the union of leftist forces (given the meager numbers they had previously) and not the result of a decided support of the electorate for the government’s policies.

The tenuous connection between national politics and regional and municipal politics in Colombia makes political forces with more national profiles, such as Uribism (Democratic Center) and Petrism (Historic Pact), relatively minor players in local and regional disputes. As happened to Uribism in 2019, the votes of the Historic Pact in 2023 do not reflect — not even close — the vote flow of 2022. This was to be expected. Instead of laying the foundations for a long process of party building and the consolidation of leadership at the local and regional levels, Petro and the Historic Pact opted, as others in the past, to “nationalize” these elections, magnifying — or rather creating — a defeat foretold.

*Translated by Janaína Ruviaro da Silva from the original in Spanish.