With the promulgation of the 2009 Bolivian Constitution, the controversial figure of judicial elections for selecting magistrates of the highest courts was introduced in Bolivia. In November 2025, after Rodrigo Paz’s new government took office, the last seven high-ranking members of the judiciary elected by popular vote (five from the Plurinational Constitutional Court and two from the Supreme Court of Justice) —who had unconstitutionally extended their mandates since 2023— were removed from office, and arrest warrants were issued against them. This outcome, which could certainly be celebrated, can also be seen as yet another case of political manipulation of the judiciary.

There is no doubt that popular elections are the purest exercise of democracy, characterized by passion, noise, and even a certain degree of disorder, as the framers of the U.S. Constitution well recognized. They were aware that a republic also requires another more serene and measured side, embodied in the judiciary, which should not necessarily be based on popular elections—at least not in the case of its highest courts.

Judicial electoral processes

In a country like Bolivia, where nothing happens without chaos, three judicial electoral processes have taken place to select magistrates of the Constitutional Court, Supreme Court of Justice, Agro-environmental Court, and the Council of the Judiciary—held in 2011, 2017, and 2024. In all cases, candidates were preselected by a legislature dominated by a hegemonic ruling party, and all those who were eventually elected became increasingly skilled in drafting rulings tailored to the government of the day. Some notorious examples from the Constitutional Court that flagrantly violated the Constitution include: authorizing former president Evo Morales to run for a third consecutive term, allowing indefinite presidential reelection, and eliminating the obligation to resign from office as a prerequisite to running for elected positions. All of this benefited Morales while he was still in power.

When Luis Arce assumed office in November 2022, the Constitutional Court adapted to the new government’s needs. It relaxed the interpretation of the permanent residency requirement for all candidacies, reversed its own earlier decision on indefinite presidential reelection, and stripped Morales of his status as party president. This is without mentioning the numerous rulings and statements used to block the election of new magistrates, extend its own mandate unconstitutionally, and promote partial judicial elections to maintain control over the Constitutional Court (in 2024, only four of the nine Constitutional Court magistrates could be elected).

However, the newly elected members in December 2024 have also faced criticism for what some see as political actions. One example is the August 2025 decision of the Supreme Court of Justice (in which seven of its nine members were elected in 2024) ordering a review of the preventive detentions of former interim president Jeanine Áñez, Santa Cruz governor Luis Fernando Camacho, and former Potosí leader Marco Pumari. This decision raises concerns not only because it referred exclusively to three politicians who symbolized opposition to the previous government—seemingly violating the principle of equal treatment for all detainees—but also because it came almost immediately after the first round of the 2025 elections, in which two opposition parties advanced to the runoff against the Movement Toward Socialism (MAS). Another controversial decision came when a Constitutional Chamber ordered the immediate dismissal of the self-extended magistrates less than twenty days after Rodrigo Paz’s new government was installed, despite failing to do so back in December 2023, when the unconstitutional extension actually occurred.

Bolivia’s high courts have been manipulated to strip the electoral body of its functions, systematically denying its own jurisdiction in order to allow electoral rules to be molded to benefit whoever is in power.

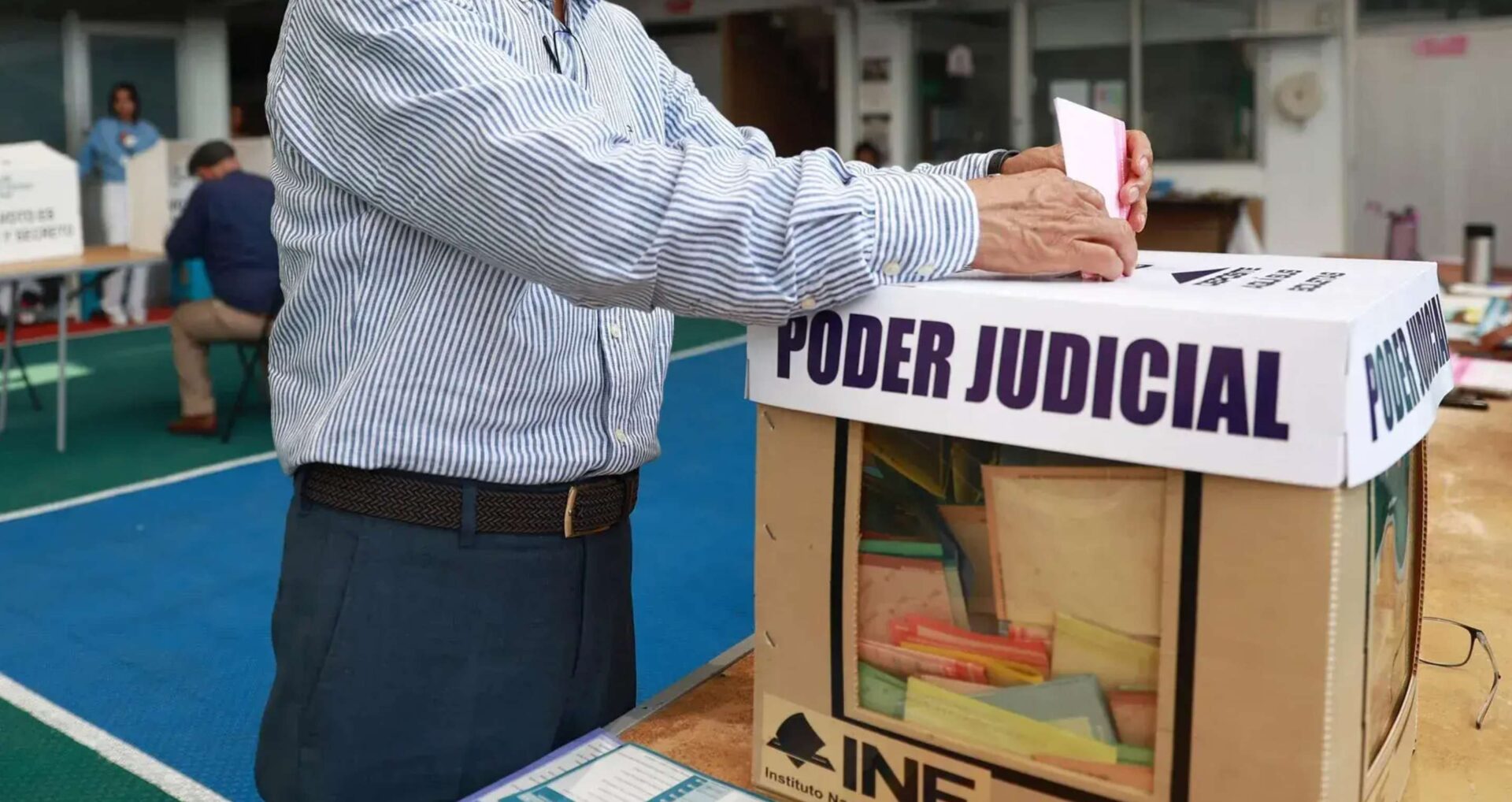

The Mexican case

In Mexico, also under the dominance of a powerful party with broad popular support, the Constitution has been reformed to introduce a system of popular elections for all members of the judiciary, including top court magistrates. The pattern repeats itself: candidates are preselected by a majority-controlled legislature with a weakened opposition, while invoking the rhetoric that “the people are wise and have the final word.”

But the Mexican reform has gone even further by including the popular election of electoral court magistrates as well. This package is dangerous because, in the name of direct democracy, the ruling party first selects the candidates, and the electorate merely ratifies them.

In Latin America, the rise of plebiscitary presidentialism—where everything is subjected to popular vote—creates a system in which checks and balances become impossible. For mechanisms of reciprocal control and sanction to function against powerful executives, state institutions must have different sources of legitimacy. Otherwise, hyper-presidential systems use popular elections to legitimize the president as the sole voice of the people.

When presidents use plebiscites as a tool of self-legitimation, it becomes essential for the judiciary to remain independent from popular elections and derive its legitimacy from another source, in order to avoid granting absolute power to the executive. If the popular election of high court magistrates is manipulated by the executive, who controls power? If anything, Bolivia’s experience with judicial elections has shown that democracy’s worst enemy may well be a kind of “super-democracy.”

*Machine translation, proofread by Ricardo Aceves.