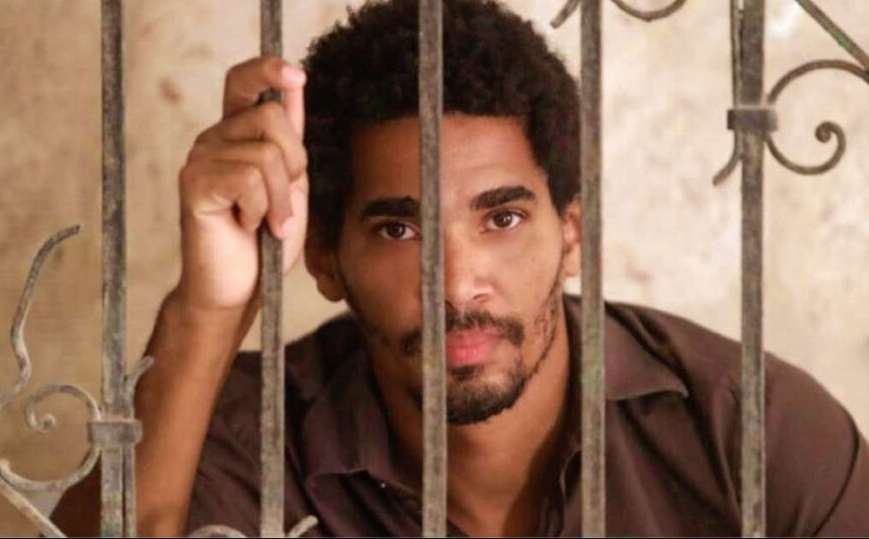

The Cuban regime is forcing one of its most celebrated dissident artists into exile, exposing its deepest fear: the power of art to mobilize dissent—and the power of the individual to inspire others for democratic change. Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara—named by Time in 2021 among the world’s 100 most influential people—embodies that threat. “I love freedom more than life itself,” he declared in 2020 after enduring dozens of arbitrary arrests—a credo that fuses his life, art, and activism. On July 11, 2021, he was arrested again as Cubans staged the largest protests in decades and later sentenced in a closed-door trial to five years in prison. From his cell, he warned: “They fabricated this five-year sentence out of nothing—out of falsehoods. They could invent another ten. So, I choose exile. But I don’t want to leave Cuba. My only options are martyrdom or exile.” His ordeal reveals how Havana weaponizes exile as punishment and erasure, silencing voices it cannot control.

Identity as Defiance

Otero embodies what the Cuban state fears most: the power of a poor, Black, self-taught artist who turned marginalization into resistance. His existence dismantles the official myth that the revolution was built by and for the poor and Afro-descendants.

In 1961, Fidel Castro invoked the murder of literacy teacher Conrado Benítez, declaring: “He was poor, he was Black, and he was a teacher. Those were the reasons why the agents of imperialism murdered him.” Today, in a cruel inversion, Otero is persecuted for those same reasons—not by imperialists, but by the Cuban state. Poor. Black. Dissident. For Havana’s poor neighborhoods, he has become a symbol of dignity, echoing the cry heard in the 1994 Maleconazo uprising and again on July 11, 2021: libertad.

Art as Resistance

Otero belongs to a long tradition of Cubans who carved out spaces beyond state control, turning culture into protest—and paying dearly through prison, with exile now looming as his next punishment. The regime fears him not only for who he is, but for his power to mobilize. He stands in a wider lineage of resistance—from underground poets in Czechoslovakia to artists in Nicaragua under Ortega and Ai Weiwei in China—proof that creativity can outlast repression.

His most enduring contribution—together with Yanelys Núñez, Maykel Castillo “El Osorbo,” and Amaury Pacheco—was founding the San Isidro Movement (MSI) in 2018. Born in defiance of Decree 349, which banned art without state approval, MSI launched a crusade against censorship and broadened Cuba’s opposition by drawing in artists, intellectuals, feminists, LGBTQ+ activists, and others long excluded from dissent.

Symbolic actions soon defined the movement. In November 2020, MSI members staged a hunger strike to denounce the arrest of rapper Denis Solís, exposing the persecution of dissident artists. Months later, Otero’s performance Garrote Vil during the Communist Party Congress dramatized the suffocation of Cuban dissenters, using the iron collar once employed for executions under Spanish colonial rule and later Franco’s dictatorship to mirror how the state strangles opposition today.

This cultural explosion reached its peak with Patria y Vida, the Grammy-winning anthem that united Otero, Castillo, and Eliéxer Márquez “El Funky” with Cuban artists in the diaspora. Like Poland’s Solidarność banner in the 1980s or Hong Kong’s Umbrella Movement, the song became an unstoppable cry of defiance— proof of the symbolic power of art to shake a dictatorship more forcefully than any weapon.

By 2021, MSI had pushed Cuba’s repression into the global spotlight. The Washington Post ran dozens of articles about the movement between late 2020 and mid-2021, while solidarity actions spread across Europe and the Americas—an eruption unseen in decades. Through inventive digital resistance, MSI livestreamed hunger strikes, sit-ins, and police raids despite constant internet blackouts. Their motto—Estamos Conectados—captured both resilience and creativity, linking Cubans on the island with those abroad.

Why He Terrifies Havana

Today, Cuba faces prolonged blackouts, poverty affecting more than 89% of households, and widespread frustration. According to the Cuban Observatory of Human Rights, public disapproval of the government reached 92% in its 2025 report, while the Cuban Observatory of Conflicts documented more than 6,000 civic protests so far in 2025—from students denouncing internet prices to communities demanding water and electricity. In this climate, leaders like Otero are seen as especially dangerous because they channel spontaneous discontent into organized resistance.

Although the San Isidro Movement was dismantled through arrests, forced exile, and travel bans, it endures as a blueprint for civic organization, digital strategy, and international solidarity.

The Voice They Cannot Banish

Otero’s imprisonment and looming exile mark a turning point in Cuba’s repressive strategy. Since July 2021, the regime has shifted from short detentions to long sentences and systematic banishment—tactics meant to erase civic leadership. Forced exile is both punishment and erasure, violating Cuba’s obligations under international law, including Article 12 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and Article 13 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Yet Otero’s legacy endures. He has shown that resistance can rise from ordinary Cubans—marginalized neighborhoods, Afro-descendant communities, the forgotten poor. The San Isidro Movement seeded a culture of protest, paved the way for July 11, and proved that art can carry repression onto the world stage. From prison, he organized symbolic fasts and created works later exhibited abroad. His resilience has been recognized worldwide, earning honors from ArtReview, the Rafto Prize, and the Václav Havel Prize.

Even in exile, Otero will remain a global voice, rallying solidarity across academia, the arts, and civil society. But true solidarity requires more than recognition: it calls for his unconditional release, an end to forced exile and re-entry bans, and the repeal of laws that criminalize art and dissent.

The persecution of a single artist—fabricated charges, a show trial, imprisonment, exile—does not show strength but weakness. Autocrats may command armies, yet they tremble before the courage and imagination of one individual who dares to inspire others.