In Brazil, the cities of São Sebastião, Londrina, Salto da Divisa, and Palhoça suffered attacks on schools in 2024. It remains to be confirmed whether these are cases of extreme violence influenced by hate speech and extremist ideologies, like the other 36 incidents that occurred between 2001 and 2023. Even if they don’t fit this specific context of violence, they are situations that raise concern.

According to UNICEF, between 50% and 70% of Latin American students are victims of bullying, especially in countries like Mexico, Colombia, Paraguay, and Peru. Beatings, injuries with objects, the use of obscene language, and even sexual abuse are alarming cases that highlight an increasingly insecure school environment. Various attacks on schools are directly and indirectly related to this phenomenon. These acts cannot be normalized, and it is the duty of civil society to contribute to ensuring that the population adopts a vigilant and proactive stance on the issue.

The four episodes recorded in Brazil in 2024 show that the number of cases remains at the same level as in the past two years. If this year’s incidents are confirmed to be cases of extreme violence against schools, 2024 will mark the second consecutive year with the highest number of attacks in the first half of the year.

But why do they no longer seem as relevant as before? Daniel Cara, coordinator of the Ministry of Education’s (MEC) working group on the issue, speaks of the normalization of these attacks by the Brazilian population. According to him, this crime is already considered ingrained in our society.

The social and political context in which these attacks have occurred in Brazil favors normalization, especially due to factors such as: the neglect of hate speech by far-right public figures, the inability to advance discussions on social media regulation, and the glorification of weapons.

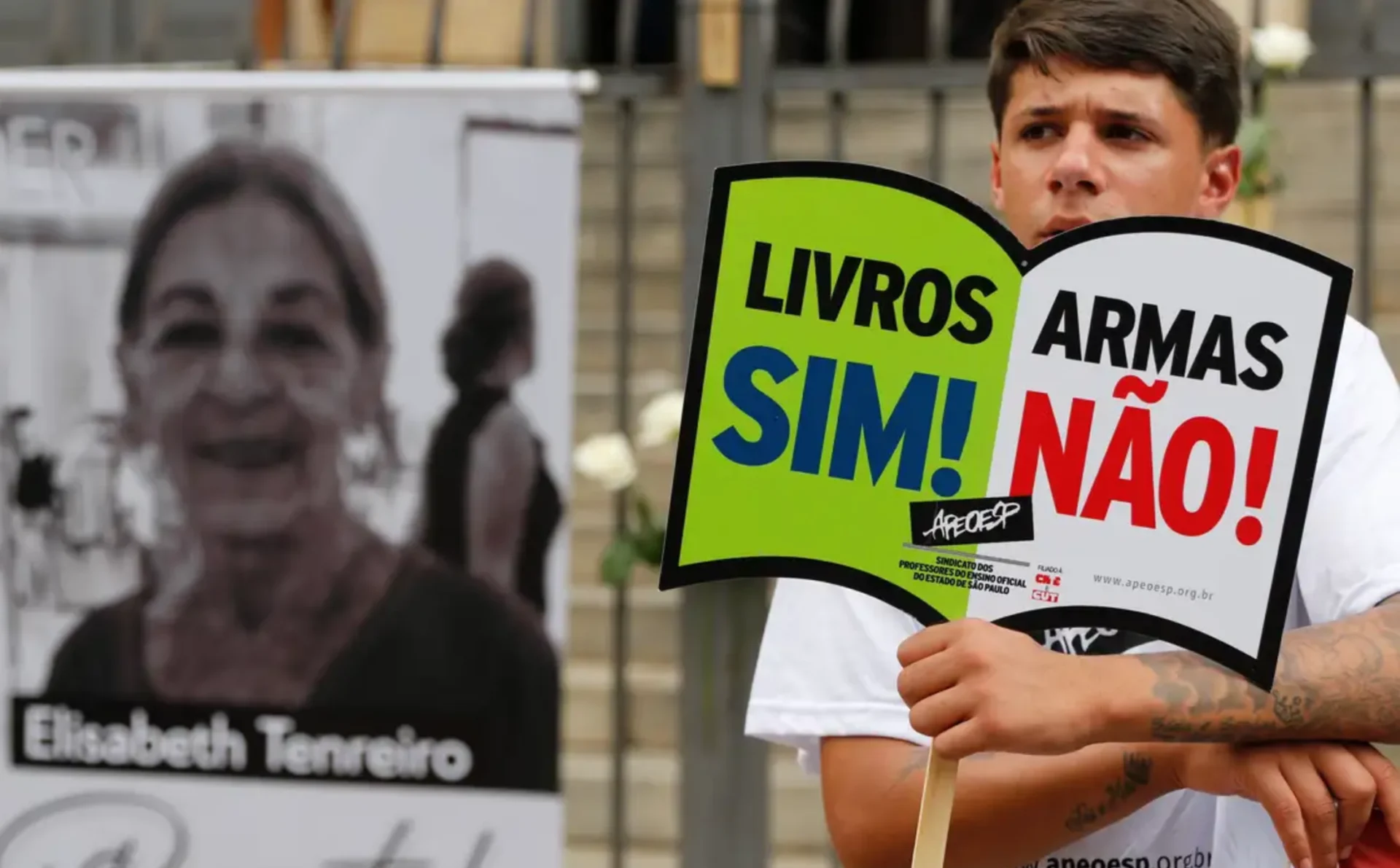

Despite the apparent normalization by the population, the problem remains at the center of political debate on the educational agenda. On one side, there are supporters of a homogeneous school education (like civic-military schools), technicist, and more focused on technical preparation for a future profession than on developing critical thinking. For this group, preventing extreme violence against schools relies solely on armed security. On the other side, there are advocates of public, pluralistic education that promotes critical thinking, democracy, and human rights, who believe prevention involves improving school coexistence.

Can security and school coexistence coexist?

At first, it may seem difficult to imagine how proposals with different approaches can coexist, but this exercise is necessary in a population divided into ideologically opposing groups, all demanding the protection of their children, youth, and adolescents.

The report Ataques de violência extrema em escolas no Brasil: causas e caminhos states that there are security measures that can be reconciled with strategies to improve school coexistence, as long as there is a conducive environment for it. These include increased vigilance at vulnerable points, panic buttons, staff training, external cameras, and proximity policing. Armed security is not an option.

In the e-book Violência contra escolas no Brasil: Perspectivas sobre o extremismo entre jovens e estratégias de prevençã, produced in partnership between Latinoamérica21 and the Instituto Aurora, with co-authorship from various civil society organizations, each article contains proposals to overcome this problem.

These proposals include: 1) Promoting a heterogeneous school that values human rights education and a culture of peace; 2) Understanding the factors that bring children and young people into contact with extremist ideologies and those that distance them from it; 3) Preventing with strategies aimed at acting rather than reacting, recognizing signs of extreme violence in advance; 4) In dealing with incidents in schools, all public policies, such as health, culture, and social assistance, must be mobilized, reducing distrust in institutions; 5) Discovering what young people seek on social media and proposing alternatives that steer them away from the path of radicalization towards extremism, helping them consider other possible masculinities; 6) Including pedagogical practices that create spaces for students to express and reflect on their media habits; 7) Building life possibilities and promoting spaces of belonging that reconnect individuals with shared, community, and solidarity experiences, preventing and rescuing young people from extremism.

The danger of a polarized debate amid normalization

In a polarized scenario, care must be taken to prevent the issue of school violence from becoming a tool to alter the population’s perception of what a school environment should be, allowing ineffective solutions to a complex problem to gain popular support.

For example, in early July 2024, the Education Committee of the Chamber of Deputies, under the presidency of Deputy Nikolas Ferreira (PL-MG), discussed bill 2380/2022, which proposed school surveillance by specialized agents, justifying it with cases of attacks on these institutions. The discussion continued around the defense of armed security in schools to combat violence against and within these institutions.

Also, in the first half of 2024, the privatization of a portion of public schools was approved by the governors of two Brazilian states (São Paulo and Paraná), both from parties supporting more conservative agendas, and this privatization includes bidding for the areas of school surveillance and reception.

In the end, not normalizing violence against schools involves preventing the next attack on these institutions, but also: 1) stopping the success of the gun lobby; 2) curbing the transfer of public money to private companies seeking their own benefit; and 3) halting a power project where schools are managed through fear.

Civil society has the duty to ensure that the population does not normalize violence against schools, guaranteeing that the debate on the issue remains public, includes the school community, circulates in mainstream media and digital platforms, and prevents it from being co-opted by extremist political groups.

Above all, it is about building a path that is not biased by far-right values and where a divided society can find ways to reconnect.