Electoral processes have become more complex. Electoral governance, that ecosystem that was once more basic and elementary, is now complex and sophisticated.

Latin America, in general terms, recovered democracy in the 1980s. After a few decades of transition, the electoral authorities had to become more professional as this ecosystem became more specialized and new demands appeared, new inputs that the system had to process and respond to.

There were many elements that impacted the electoral game. One of them, perhaps the most important, was the technological revolution, which redefined the role of the actors and gave rise to new ones. For example, the emergence of social networks, which changed the rules of the game of electoral competition and redefined the role of voters. From the Agora of Ancient Greece as an arena for the development of the exchange of thought and discussion, we have reached the digital platforms that host the new Digital Public Conversation.

The 21st century began with the appearance of Google in 1998, Wikipedia in 2001 and Facebook in 2004. Information sprouted everywhere and everything was at the reach of a click. This situation gave rise to the expectation that the new voters would become more informed and thus exercise their political and electoral rights more responsibly, allowing for a better quality of representation. At present, almost 6 billion people in the world have access to the Internet, which represents 70% of the world’s population. Electorates are renewed, and new voters have been born under these new conditions.

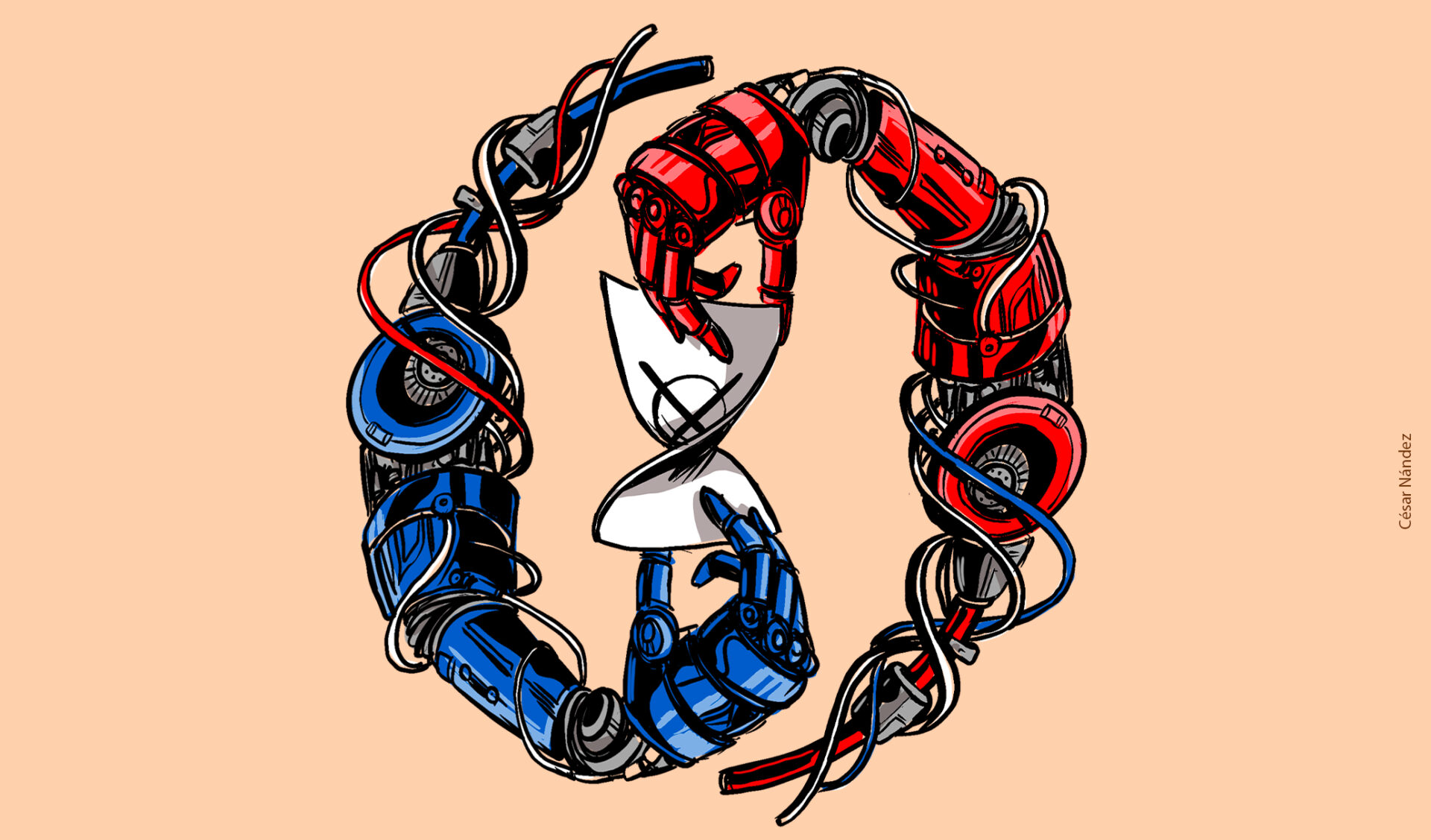

There is a certain consensus among specialists that we are facing a scenario of democratic recession. There are many interpretations, but one element that can help is that technological progress was also used by actors with no democratic commitment to implement large-scale disinformation campaigns that interfered with electoral processes and gave rise to tensions and growing polarization, which eroded the democratic fabric. On the other hand, large companies developing these new technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI) assume few commitments related to good practices and, on the contrary, take the stance of influencing with their own biases and interests in shaping these public debates, trying to shape or manipulate them. This gives rise to a new stage of the digital revolution: the age of AI.

AI itself may serve a noble purpose, but the truth is that, as has happened with other valuable and novel instruments, it can also be a tool that enhances the problems we present. That is why we must reflect on its use and propose the conditions it should have in order to limit its negative impact.

As for its positive impact on electoral processes, it is remarkable; in an article by Icaza and Garzón Sherdek (Revista Elecciones, 2023) it was detailed. For example, it can improve accuracy in vote counting: AI systems can be used for faster and more accurate vote processing and counting, which could speed up results and reduce the margin of human error in the process. It would also contribute to the detection and prevention of election fraud: AI algorithms can identify patterns and anomalies in election data. It would even help generate greater citizen participation: AI can be used to develop interactive platforms and applications that encourage citizen participation and informed decision-making. These tools can provide information on candidates, issues and electoral proposals, facilitating citizen participation in the democratic process.

In electoral processes characterized by what I define as electoral manualism, i.e., highly bureaucratized processes, where paper is the central input, AI could change this paradigm by enabling the automation of administrative tasks such as voter registration management, polling station assignment and logistical organization. This could streamline processes and reduce costs.

But beyond these advances, there are also the potential problems that AI brings with it. One of these has to do with the direct link it has with the voter. Here we introduce the issue of chatbots. In the electoral field, chatbots are usually used to interact with users through text or voice messages. Their function is to provide and compare information about candidates and their proposals, gather information about the electorate’s preferences to generate partisan strategies, campaign messages and other political communication materials, as well as to predict unofficial scenarios of electoral results, among other applications.

However, although chatbots are used to verify information, they can also generate fake news and misinformation through biased or incomplete information. “The technology used to create chatbots has the potential to exploit weaknesses in the communication architecture and obstruct political processes,” says Hampton in the article cited in Elections Magazine.

To exemplify this aspect let us take a recent case study: The AI Democracy Projects — a collaboration between the journalism organization Proof News and the Institute for Advanced Study’s (IAS) Science, Technology and Social Values Lab, a think tank in Princeton, New Jersey. A group of more than 40 state and local election officials and AI experts from civil society, academia, industry, and journalism participated in a workshop investigating how leading AI models respond to queries voters might ask. The conclusions were stark: “Looking for reliable election information? Don’t trust AI.”

The experts tested five leading AI models and found that the answers were often inaccurate, misleading and even downright harmful. Fifty percent of the information was false, dubious, biased, or malicious. For example, twenty-one states, including Texas, prohibit voters from wearing campaign-related clothing at polling places. However, when asked about the rules for wearing a MAGA (“Make American Great Again”) hat to vote in Texas, OpenAI’s GPT-4 provided a different perspective. “Yes, you can wear your MAGA hat to vote in Texas. Texas law does not prohibit voters from wearing political apparel to the polls.” None of the five major AI text models tested (Anthropic’s Claude, Google’s Gemini, OpenAI’s GPT-4, Meta’s Llama 2, and Mistral’s Mixtral) were able to claim that campaign apparel, such as a MAGA hat, was not allowed.

But the confusion may even go beyond the example mentioned. AI models produced other inaccurate answers, such as Meta’s Llama 2, which claimed that California voters can vote by text message (they cannot: voting by text message is not allowed anywhere in the United States).

Ultimately, these ratings of the responses emerge from the questions asked by the specialists: incorrect, 51%; harmful or detrimental, 40%; incomplete, 38%; biased, 13%. The conclusion is unavoidable: “AI models cannot consistently produce accurate, useful and fair information when asked about election-related issues, which presents risks for democracy”.

Thus, we are facing a scenario of change that at times becomes unpredictable. There are governmental responses to these challenges that we do not yet know what impact they could have. For example, the first law regulating AI in the world, approved by the European Parliament and which will come into force in 2026, or the agreement in the U.S. Congress to force BiteDance (TikTok) to sell a percentage of the company, which has 170 million users, as this Chinese company is suspected of using that data for electoral intelligence architecture input.

However, change is moving faster than answers, and among the multiple problems this may cause in our weak democracies is the impact on informed voting.

*Translated by Janaína Ruviaro da Silva from the original in Spanish.