The reduction of the workweek to four days or a maximum of 32 hours while maintaining salary has recently been successfully tested in countries such as Iceland, New Zealand, Japan, the United Kingdom, and Spain. In Iceland, between 2015 and 2019, a pilot project involving more than 2,500 workers showed that shorter hours improved productivity and well-being and also fostered better work-life balance (Haraldsson & Kellam, 2021).

Most formal jobs involve eight or more hours per day in the office—excluding commuting—which represents more than half of a person’s active daytime. Added to this is the fact that many people work five or six days a week, leaving only one or two days for full family time. As a result, people end up sharing more time, conversations, and even emotions with colleagues than with partners, children, parents, or friends. This has been part of a lifestyle increasingly questioned, especially by younger generations.

In 2021, the WHO and ILO reported that long working hours cause around 745,000 deaths per year worldwide, due to strokes and ischemic heart disease, representing one-third of total work-related deaths. Working six days a week, often exceeding eight hours per day, leaves almost no time to rest, be with family, enjoy leisure, or engage in self-care.

Specifically, in Latin America, the average workweek exceeds 44 hours, and in many cases, workers complete six-day cycles, with all the physical, psychological, and social consequences that such a workload generates.

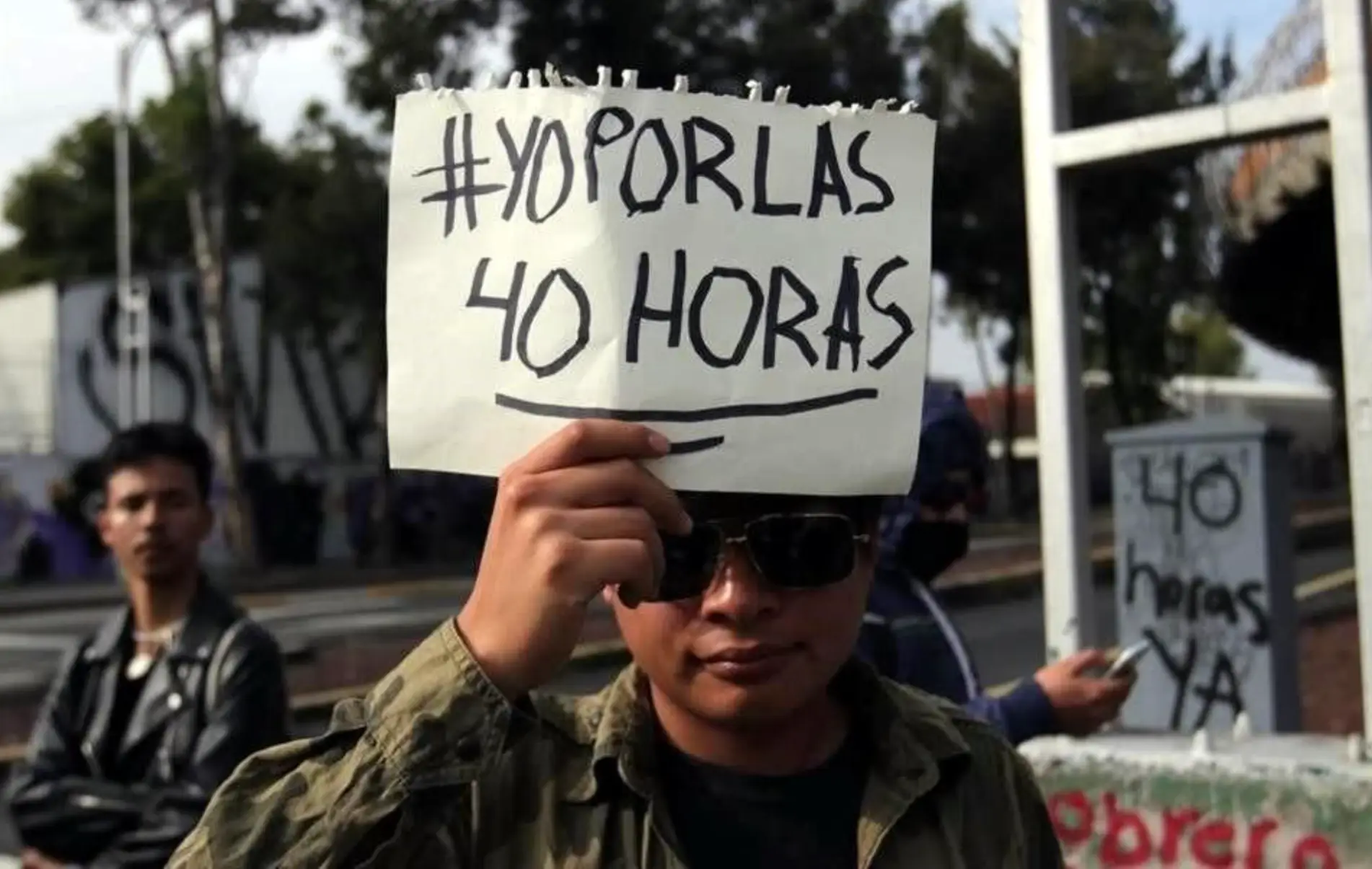

However, steps are being taken to reduce working hours in countries like Chile (in 2023, hours were reduced from 45 to 40), Uruguay (although not legally reduced, a strong union movement discusses the issue as part of a progressive labor agenda), Colombia (in 2021, a law was passed gradually reducing the workweek from 48 to 42 hours by 2026), and Mexico (a constitutional reform is being debated to reduce hours from 48 to 40 per week, with strong social and union pressure).

Even though progress is uneven, in many Latin American countries, the discussion about reducing working hours is gaining ground in political agendas, particularly when linked to issues such as declining birth rates and other demographic concerns.

Why a gender perspective is key in this policy

Excessive workloads are far from gender-neutral, as they disproportionately affect women, who, in addition to facing adverse working conditions, carry most of the unpaid domestic and care work.

For many Latin American women, work does not end at the office or factory door; another labor begins at home, in a grueling and often invisible double shift. According to data from the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), women in the region dedicate an average of 4 hours and 25 minutes daily to domestic and care work, while men spend only 1 hour and 23 minutes. This means women perform more than three times as much of this work. These tasks are essential for sustaining families and communities, yet traditional economic systems neither account for nor recognize them as labor.

This almost three-hour daily gap reveals a structural inequality that limits women’s economic and personal autonomy and exposes them to higher levels of stress, exhaustion, and social exclusion.

Reducing the workweek to four days should not simply be a measure to rest more or boost productivity. Instead, it could be a political tool to redistribute time and break the chains that bind women to double or triple shifts. Additionally, it could open space for shared responsibility in care work, recognized as a human right by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights on August 7.

Reducing hours without considering inequality can worsen gender gaps

It’s not just about gaining free time but about ensuring that shared responsibility in care work becomes real and effective. If a male worker uses the day off for rest or personal activities while a female worker uses it for household labor, inequality persists. Without a gender-focused approach recognizing structural disparities, the extra day off can end up being another day of invisible work for women.

Therefore, formal workweek reduction must be accompanied by robust public policies that recognize and redistribute care work: universal and accessible daycare and child care centers, equal and non-transferable parental leave for men and women to encourage shared caregiving, educational campaigns to promote co-responsibility at home, and dismantling patriarchal stereotypes that normalize women as the exclusive caregivers.

Failing to do so increases the risk that reduced working hours will continue to overload women, who will use that time to continue domestic and care tasks that the state and market fail to provide.

We cannot accept that, in the 21st century, millions of Latin American women continue to bear endless work hours that prevent full development and greatly limit political and economic participation, wealth accumulation, and well-being.

Transforming work time must also be a fight against patriarchal culture that naturalizes women as primary caregivers and renders domestic work invisible. Hopefully, discussions will arise allowing the design of new social organization models where care is a collective and valued responsibility.

It is not just about working less, but working better and living more equally and fairly between women and men.

*Machine translation, proofread by Ricardo Aceves.