Artificial intelligence (AI) is a technology that is reshaping social, economic, and cultural life in real time. In Latin America, its adoption is advancing rapidly, but on uneven ground: with major access gaps, limited digital literacy, and stalled regulatory debates. In a region marked by overlapping structural inequalities, the urgent question is not whether Latin America is ready for this technological wave, but who will be left behind — and who will pay the highest costs. Women, especially those who are poor, racialized, and rural, face the risk of becoming the main losers of this revolution unless feminist perspectives are incorporated from the outset into public and technological policy design. In this context, one question emerges: What kind of AI do we want for ourselves?

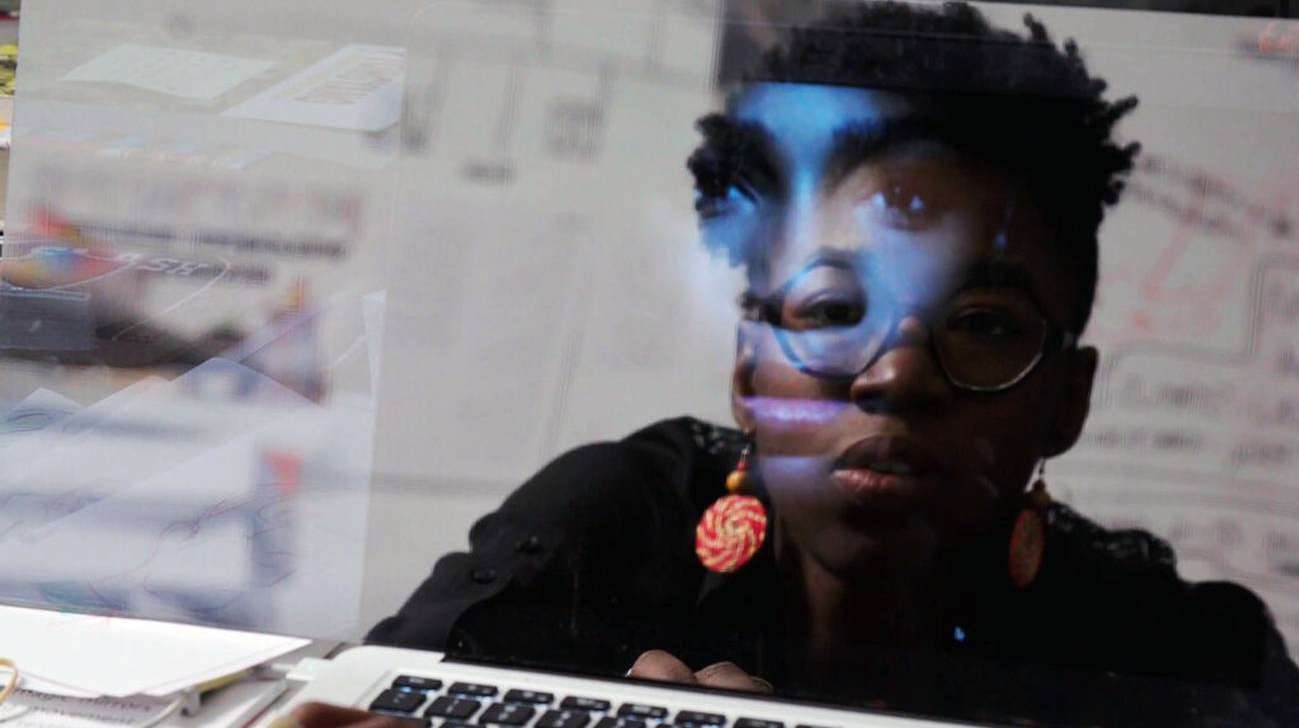

That does not mean AI brings no real opportunities. There are thoughtful yet optimistic views that argue artificial intelligence can open historic employment opportunities for women. For instance, tools like ChatGPT or Gemini make it possible to participate in tech projects without needing months of programming training. This could democratize access to tech careers for women. In a continent where only 28% of technology jobs are held by women, according to the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), AI can serve as a gateway to economic autonomy and better-paid work, especially for women in precarious labor conditions.

But these opportunities are not universal. According to the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), 32% of women in the region do not have regular internet access, and the gap widens to 42% among rural women. In many households, mobile phones are shared devices — and when it comes to deciding who uses them, the answer is often predictable. In rural areas, women frequently lack their own phones. As a digital rights expert has pointed out, discussing AI without addressing digital inequality is like pretending we all start from the same place.

To this material divide we must add another, less visible but equally serious one: the representation gap in technological development. Since AI learns from the world through data — and that data is imbued with sexist, racist, and classist biases — it inevitably reproduces and amplifies discrimination. This is not theory. As early as 2018, Amazon’s automated hiring system was found to automatically discard women’s résumés because it had been trained on data from male employees. Similar problems occur with opaque algorithmic credit models that penalize intermittent work histories — a common pattern among women due to caregiving responsibilities. What might appear as a lack of commitment is, in fact, a manifestation of structural inequality. These examples show that the problem originates in the historical inequalities embedded in the data used to train the algorithms.

Perhaps the field where AI has most harmfully impacted women is digital violence. Today, deepfakes are a new weapon for gender-based aggression: fake videos that sexualize women’s faces without consent, fraudulent audio clips, and digital smear campaigns. It is estimated that 90% of deepfakes online are non-consensual sexual content, and 95% of those target women. This threat affects journalists, teachers, activists, and teenagers who have been victims of extortion and harassment through fabricated images. Without regulation or accountability, AI risks becoming a technological amplifier of the very forms of violence societies are trying to mitigate.

However, while women remain underrepresented in technological development, they are also creating critical alternatives. One example is OlivIA, an artificial intelligence tool built within the ChatGPT ecosystem by Argentine lawyer and feminist communicator Ana Correa. OlivIA functions as an “interventionist AI,” detecting gender bias in texts, policies, speeches, or content and offering critical questions. Among its prompts: Are you leaving someone out? Did you check if the disease symptoms differ between men and women? Who is telling this story — and who is missing? This tool draws inspiration from feminist legal theory methodologies, particularly Katharine Bartlett’s “woman question,” and was trained on human rights frameworks and gender justice debates.

The relevance of OlivIA lies in its challenge to the notion of technological neutrality — the idea of erasing bias altogether. From the perspective of affirmative action, what we actually need is not to hide bias, but to expose and address it.

Meanwhile, states are not responding quickly enough. Latin America remains behind on AI regulation. The European Union has already approved the AI Act to establish ethical limits on AI use, yet the region still lacks a common framework or comprehensive protection policies. Concerns persist over transparency and the risks of relying too heavily on corporate self-regulation.

International organizations like the United Nations have called for the incorporation of a gender perspective in AI governance to prevent the reproduction of digital violence and inequality. Thus, we must ask again: What kind of artificial intelligence do we want for Latin America? Bringing AI to the public agenda — and not remaining passive users — is urgent. If we do not engage in this debate, someone else will. And if that future is designed without us, it will also decide over us.

*Machine translation, proofread by Ricardo Aceves.