Since November, a growing trend in the number of new daily cases and deaths from Covid-19 has been confirmed in the Americas, which are now the epicenter of the global pandemic. The lethal course continues in the region, holding more than half of the world’s cases and deaths, with the U.S. and Brazil leading sadly this statistic. About 30 million cases and 800,000 deaths were recorded from the beginning of the pandemic until Dec. 12. These figures include 14 million cases and 500,000 deaths recorded in Latin America. Brazil is close to 200,000 deaths and 8 million cases. However, all these numbers, hemispheric, sub-regional and national, are surely higher, because the access to testing is poor and many deaths have yet to be confirmed.

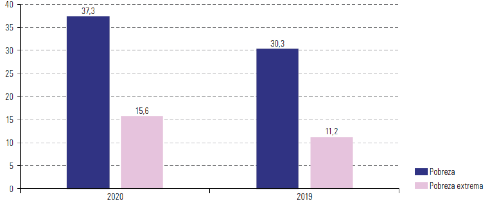

Why has Latin America been so intensely buffeted by the pandemic? Firstly, because of the severe poverty in which a large part of the population lives in. The Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) estimates that people in poverty, which has been rising since 2017, surged from 185.5 million in 2019 to 230.9 million in 2020, an increase of 45.4 million people (Figure 1). This means that today, 37.3% of Latin America’s population lives in poverty.

Figure 1. Population in poverty, Latin America (18 countries), in %

2019-2020

Furthermore, ECLAC projects that the Gini coefficient would increase between 1% and 8% in the same period, with the region’s largest economies showing the worst results.

In addition to income inequality, the Covid-19 pandemic has opened up other dimensions of inequality in Latin America: The poorest populations, Blacks, indigenous people, residents of the peripheries, slums, quilombos, and villages are the ones most affected by the disease. It is very clear that the population’s vulnerability also grows astonishingly with poverty and inequality: the poorer the populations, the more susceptible to get sick from Covid-19 are and the greater the fatality, i.e., deaths per case.

The countries’ health authorities (and national leaders) are astonished and often lost and they are failing to act efficiently to mitigate or attenuate the social, economic and health consequences caused by the pandemic. In Brazil and Mexico, the situation is even more chaotic, given their presidents’ negative stance toward the overall situation and incompetence of their respective ministries of health.

Nevertheless, a number of heterogeneous proposals are being formulated to face this calamitous situation, both at national and regional levels, and with the sub-regional arrangements of countries.

Regional health diplomacy in multilateral and plurilateral responses

The hemispheric arm of the World Health Organization (WHO), the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), which, on 10 December, gathered all health ministers of the Americas, discussed ways to make vaccine distribution in the region equitable, including the mechanism of the Revolving Fund for Vaccine Procurement, which has existed for many years with great efficiency in the Organization.

Amid growing concern about the rising number of contagions in the region, ECLAC and PAHO together published in July, the document Health and the economy: A convergence needed to address COVID-19 and retake the path of sustainable development in Latin America and the Caribbean. Since then, both institutions have pointed out that if the contagion curve isn’t controlled, it won’t be possible to reactivate the economies of countries and of the region as a whole. It also indicated that both, pandemic control and economic reopening require leadership and an effective and dynamic rectorate of states, through national strategies that integrate economic, social and health policies. The document advocates for an increase in fiscal spending to control the pandemic and buttress reactivation and reconstruction, in addition to being more effective, efficient and equitable, so that public spending for health would reach at least 6% of GDP.

Other proposals conveyed by ECLAC in the economic and social field include the paper presented to member states at the 38th session: ECLAC Session, Building a new future: a transformational recovery with equality and sustainability.

ECLAC, under Mexico’s presidency, has sought to place the Covid-19 topic on the agenda of the Latin American debate without much success. Brazil, on the other hand, a historical regional player, has renounced all demands for leadership on the pandemic at a regional level and has shown no willingness to actively participate in shaping the world after the pandemic. In fact, Brazil and even Mexico have not been the best examples in their approach to the epidemic in their own territories.

In an article published in L21, Detlef Nolte makes an appropriate analysis of the Covid-19 side effects on Latin America’s integration. He points out that “the Covid-19 crisis ruthlessly exposed the structural deficits of Latin American regionalism. A crisis can also be an opportunity. But this requires leadership and a common agenda.” For the author, unlike the European Union, there is not strong enough leadership in Latin America –whether singular or shared– that can promote regional projects or end the paralysis that some regional organizations are suffering.

In Mercosur, Presidents Bolsonaro and Fernández met in early December, seeking to resume ties weakened by political-ideological issues and prioritize issues of common interest to both countries. At the same time, the LXVII Meeting of Ministers of Health of the Mercosur took place on 3 December, resulting in four statements: 1) on the importance of ensuring environmental and worker health within the context of the pandemic; 2) on food assistance to vulnerable populations in the scope of Covid-19; 3) on tobacco control and Covid-19; and 4) on the WHO COVAX mechanism.

It also encourages support to the WHO COVAX mechanism to ensure that countries’ ability to pay doesn’t become an entry barrier to obtain Covid-19 vaccines, a situation that would leave a number of Latin American countries unprotected and would lead to this pandemic lasting longer than necessary. It also proposes a representation of Mercosur countries in the governance bodies of that mechanism. Uruguay then passed the pro-tempore presidency of the Council to Argentina.

PROSUR –the industrial property cooperation system in Latin America and the Caribbean– created five Working Tables to make all commitments established by the presidents operational: Migration and Borders; Joint Procurement; Access to International Credits; Epidemiology and Availability of Data; and Transit of Goods, which are in a preliminary phase of action.

ECLAC believes that in order to face the health crisis and its serious social and economic effects, “political and social pacts are needed to be built by a wide variety of actors to achieve universal social and health protection, redirecting development on the basis of equality and fiscal, industrial and environmental policies towards sustainability.

After all, it is a proposal of “a welfare state that assures universal access to health, redistributive taxation, increased productivity, better provision of public goods and services, sustainable management of natural resources and increase and diversification of public and private investments”. To this end, “regional and international solidarity should contribute to building on common values and shared responsibilities for progress for all.

As exposed above, all multilateral and plurilateral organizations in Latin America have established agreements that could be assessed to be integral to fight Covid-19. This is good news. With this arsenal of statements and resolutions, the necessary political basis is given. Public authorities now have responsibilities that they cannot transfer. Only transformed states, with committed governments, adequate governance and civil society’s mobilization, will be able to transcend the rhetoric of these demonstrations and find the national and subregional mechanisms to put them into practice, as well as the financing of indispensable and impossible social, political and health measures.

*Translation from Spanish by Ricardo Aceves