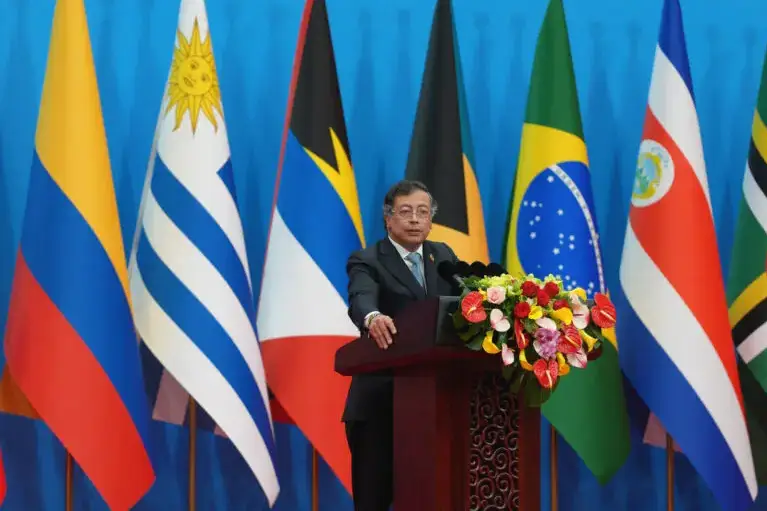

Colombian President Gustavo Petro recently assumed the pro tempore presidency of the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC). As part of this broader effort to frame himself as Latin America’s leader, Petro stated during a cabinet meeting that he would attend his visit to China as president of CELAC, adding, “I am now twice president — president of Colombia and president of Latin America and the Caribbean.” This self-proclaimed dual presidency encapsulates Petro’s diplomatic ambition to assume a regional leadership role. In fact, in just six months, Petro has made two official visits to Haiti, pledging support to combat gang violence and announcing the reopening of a Colombian embassy in Port-au-Prince. These diplomatic gestures reflect his broader vision of Latin American solidarity and South-South cooperation.

However, while Petro strengthens Colombia’s presence abroad, his government is struggling to contain a deepening security crisis at home. Armed groups are regaining strength, violence is surging, and the institutions responsible for public order are fragmented. Although Petro seeks to elevate Colombia’s role on the global stage and frame himself as a leader of Latin America, a president cannot lead abroad while losing control at home.

A nation in crisis

Petro, Colombia’s first leftist president, took office in 2022 on a political platform promising transformative change, including a new approach to internal conflict. Central to that agenda is the “Total Peace” initiative: a policy aimed at negotiating the demobilization and reintegration of both political and non-political armed actors. In practice, however, the policy has faced major implementation challenges and has failed to contain the resurgence of violence.

Since May 2025, Colombia has experienced a wave of attacks by armed actors, primarily dissidents of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC)—the guerrilla group that signed a peace agreement with the government in 2016—along with members of the Clan del Golfo, among others. This has included armed offensives in several departments, car and motorcycle bombs, and the targeting of civilians, police, and public officials, including assassination attempts of various political candidates.

The crisis, however, goes beyond security. Petro’s cabinet has experienced frequent changes, leaving key ministries without consistent, strong leadership. Emblematic of this trend is his relationship with Vice President Francia Márquez, Colombia’s first Afro-Colombian woman in the role, which has visibly deteriorated. Once cheered as a political phenomenon, Márquez recently remarked, “I went from being a heroine to a traitor,” highlighting her isolation from Petro’s inner circle and her increasing absence from public leadership. These internal struggles have also impeded his ability to secure major legislative victories. Even his latest justice reform bill, aimed at reviving the “Total Peace” policy, faces criticism for potentially reinforcing impunity.

You can’t lead abroad if you can’t govern at home

Colombia’s institutions are under severe strain. The government is politically fragmented, and there is no clear framework to confront the security crisis with consistency or authority. Despite these challenges, Petro has pursued an active leadership role abroad. Petro has made South-South cooperation and regional unity a cornerstone of his foreign policy. During the recent CELAC summit, he stated: “My mission will be to help connect Latin America and the Caribbean with the entire world, to be a bridge to the world, and to build a collective sense of self.” The comment reflects his integrative vision of leadership, one that seeks to articulate the region’s voice on the global stage. But his message of inclusion is undermined by the domestic situation.

This pattern is not unique to Petro. Across Latin America, it is common for leaders to seek regional leadership and claim the role of the region’s voice abroad, even as domestic governance falters. Although these efforts to foster unity and cooperation are valuable in a region marked by fragmentation and political polarization, a government that aspires to represent Latin America on the global stage must first demonstrate the capacity to lead its population with coherence and legitimacy. Petro’s ability to lead abroad is fundamentally compromised by his inability to govern at home. Without institutional cohesion and domestic authority, international diplomacy lacks credibility. Addressing Colombia’s crisis will require more than symbolic diplomacy or legislative experimentation. It demands institutional clarity, sustained investment in justice, and enforcement.

Restoring internal order will require more than diplomatic headlines or symbolic leadership. It will require clear management and coordinated institutions, capable of building consensus rather than amplifying polarization. A country cannot project power abroad while unraveling at home. What Colombia needs is not greater diplomatic visibility, but coherent and sustained action at home.