Over the last decade, in its aspiration to consolidate itself as a hegemonic actor in different regions of the Global South—from Africa and the Asia-Pacific to Latin America—China has sought to win the minds and hearts of public opinion through major infrastructure investments under the umbrella of the Belt and Road Initiative, accompanied by rhetoric designed to contrast with the historical debts of Western powers.

From there, China has promoted formulas such as “horizontal relations,” “South-South cooperation” and, above all, “non-interference” in the internal affairs of other countries as guiding principles of its foreign policy, in open opposition to the image of U.S. interventionism marked by decades of military operations and national security agendas in Latin America.

Donald Trump’s return to the White House reinforced this narrative. The unilateral moves of the 47th president against his own allies—the imposition of tariffs, the withdrawal of international cooperation, the distancing from multilateral organizations—made it easier for Beijing to present itself as a responsible power, open to dialogue, consensus and cooperation among equals. It is no coincidence that, during this period, China pushed forward trade agreements with South Korea and Japan—two of its closest regional competitors—defended international arbitration mechanisms such as the OIMed, and advanced quickly in areas where USAID’s retreat left a visible vacuum.

However, recent events reveal a pattern difficult to reconcile with that image. Behind the discourse of neutrality and mutual respect that the PRC projects toward the Global South, there persists a political practice that contradicts its own declared principles. Wherever a government, legislator or candidate questions the issue of Taiwan—a particularly sensitive point for the Communist Party—Beijing abandons diplomatic prudence to exert direct pressure, issue public warnings or openly interfere in domestic debates. From the Pacific to the Caribbean, these episodes confirm that China is far from the responsible power it claims to be.

The non-interference doctrine under scrutiny

Three recent episodes illustrate this contradiction well. On November 7, 2025, Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi stated that Japan would assume “historical responsibilities” in the event of any Chinese aggression against Taiwan. Beijing’s reaction was immediate and, to a large extent, illustrative of its wolf-warrior diplomacy. Among comments reported by the Japanese press, a Chinese diplomatic official even insinuated that Takaichi “deserved to lose her head” for her statements, a phrase that—beyond its tone—reveals how openly confrontational Chinese rhetoric has become when the Taiwan issue arises.

The episode was not limited to verbal statements. Beijing accompanied these remarks with threats to restrict the supply of rare earths and with travel advisories directed at its own citizens to discourage tourism to Japan. Taken together, these gestures fit into an already familiar pattern: disproportionate responses meant to punish any public stance contradicting the official narrative on Taiwan.

Precedents help explain this reaction. In 2010, after an incident in the Senkaku Islands, China effectively halted the exports of strategic minerals to Japan. In 2011, Norway faced tacit restrictions on its salmon exports after the Nobel Committee awarded its prize to Liu Xiaobo, a Chinese human rights activist.

In 2021, Lithuania was subjected to a campaign of economic coercion after allowing the opening of a Taiwanese representative office in Vilnius. And in 2024, Guatemala suffered an undeclared embargo on cardamom—one of its main export products—after the government reaffirmed its diplomatic relationship with Taipei. Economic coercion is thus a habitual instrument of Chinese foreign policy.

The other two Central American episodes point in the same direction. Recently, in Honduras, the Chinese embassy demanded that a presidential candidate retract his statements in favor of Taiwan and reminded “political forces” that this is a matter of “high sensitivity.” The warning omits something fundamental: although recognition of the “One China” principle is a condition for establishing diplomatic relations, this commitment is limited to official exchanges between foreign ministries.

It does not prevent parties, legislators or candidates from expressing political opinions or maintaining non-governmental contacts. In fact, Beijing uses these very spaces—inter-parliamentary, partisan—to project its influence in countries that still recognize Taipei. Attempting to control them reveals the self-serving flexibility of its non-interference doctrine.

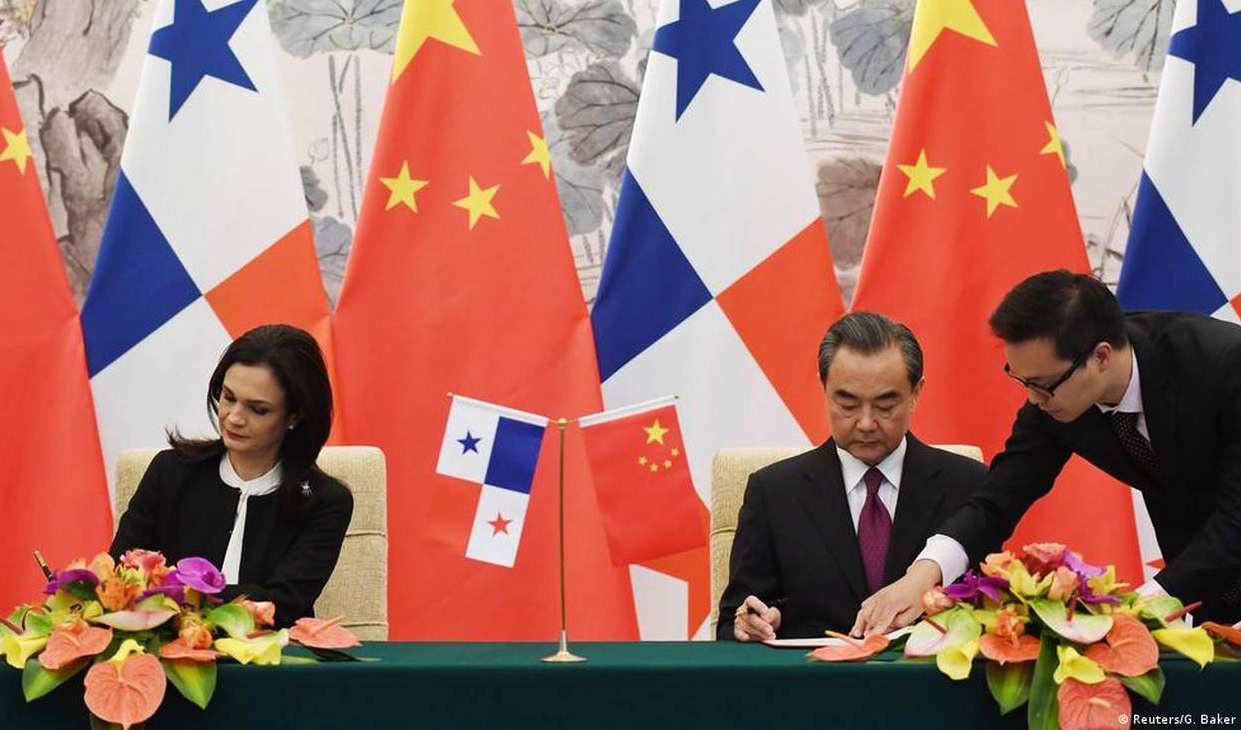

Something similar is happening in Panama. While a delegation of Panamanian legislators is currently visiting Taipei, the Chinese embassy issued an unusually severe warning, insinuating that this trip could “damage mutual trust” and “affect the fundamental interests” of the PRC.

The Panamanian foreign ministry responded by noting that lawmakers act with constitutional autonomy and that their travel does not constitute official foreign policy. For Beijing, however, any gesture—even informal—that legitimizes Taiwan is treated as a provocation.

From the Pacific to the Caribbean, these cases demonstrate the gap between China’s rhetoric of non-interference and its actual behavior. When governments, parliaments or political actors speak out about Taiwan, Beijing abandons neutrality and deploys economic pressure, diplomatic warnings and explicit attempts at discipline. Non-interference operates as narrative; intervention, as practice.

Taiwan as a backdrop

As Professor Miles Yu notes, Beijing’s disproportionate reaction to any international gesture toward Taiwan rests on a fragile legal and historical architecture. China often invokes UN Resolution 2758 as proof of its sovereignty over the island, when the text simply recognizes the government of the People’s Republic as “the only legitimate representative of China” at the United Nations.

It does not mention Taiwan, does not require unification, and does not authorize territorial claims. The Chinese interpretation is—as Yu argues—a later political construction, more useful as a tool of pressure than as a legal argument.

To this is added an undeniable historical reality: the Communist Party has never governed Taiwan. Since 1949, the island has developed its own institutional order, democratic and functional, completely separate from the mainland. In this sense, the irony circulated from Taiwan in referring to the PRC as West Taiwan works less as mockery and more as an uncomfortable reminder that historical continuity does not support Beijing’s sovereignty claim; if anything, it undermines it.

Finally, there is an even deeper political concern. Taiwan demonstrates—to Asia and to the world—that a democratic, open and prosperous Chinese society can exist without a single party or an authoritarian bureaucracy shielded by development. That example, more than any diplomatic statement, is what Beijing is determined to contain.

*Machine translation, proofread by Ricardo Aceves.