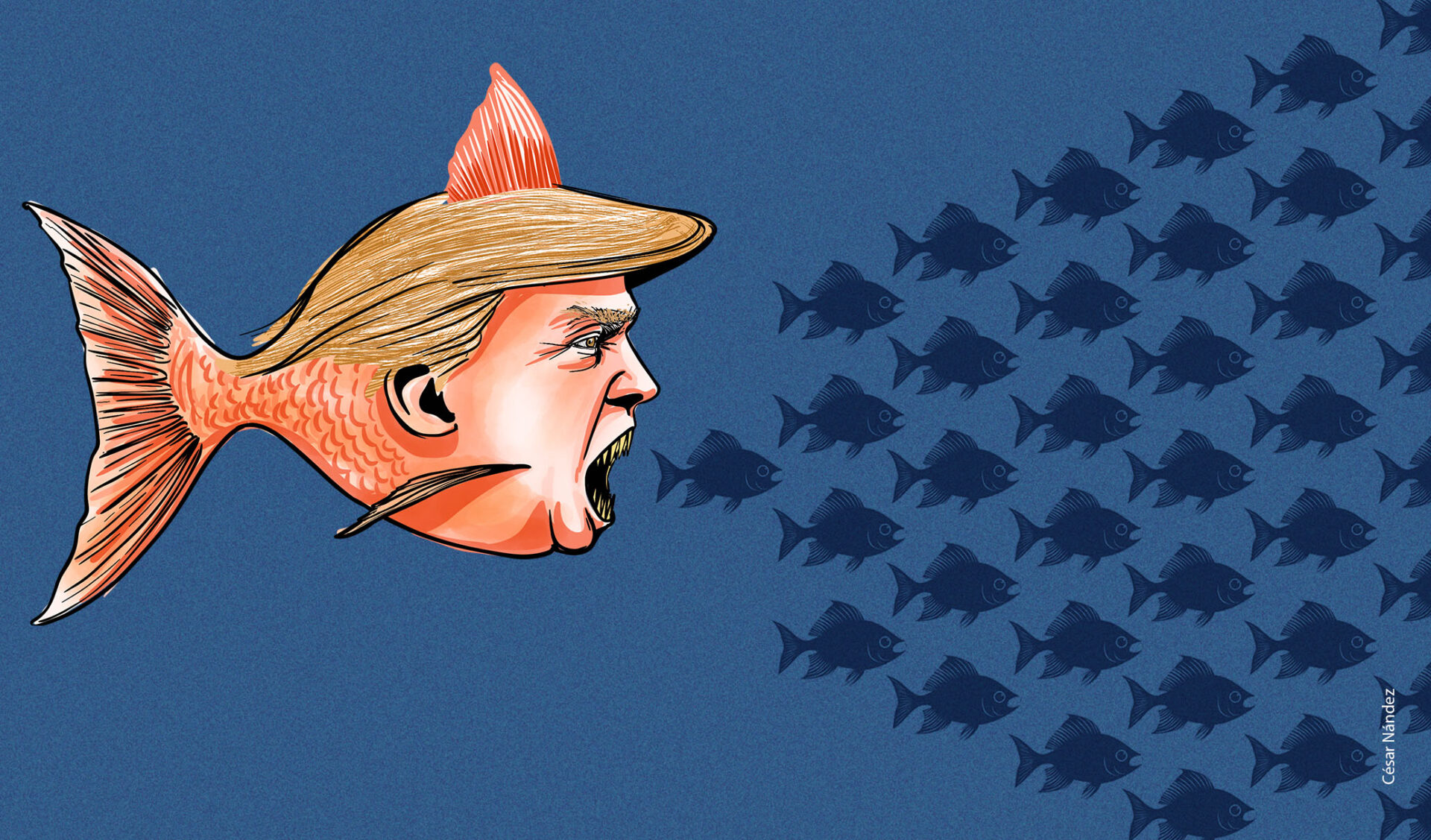

Under Trump’s New Administration, the United States seems to rediscover the importance of Latin America. But what is behind this move, and what does it indicate about global geopolitical trends?

This shift suggests a redirection of the United States’ strategic priorities, moving them away from Russia’s sphere of influence in Eastern Europe toward its own domain in the Americas. As the war in Ukraine approaches its third year, Trump has expressed his desire to de-escalate the conflict and has shown disdain for NATO, which he views as an instrument through which Europe drains American resources. Unlike Biden, who viewed the world through the ideological lens of the Cold War, Trump takes a more pragmatic, power-based approach, disregarding the norms of the liberal international order.

With Trump’s return to power, a new geopolitical landscape appears to be taking shape. The narrative of confrontation between democracies and authoritarian regimes, used to justify U.S. involvement in Ukraine through NATO, is giving way to a more ruthless logic under the slogan “America First”: the United States against the rest of the world, willing to project its power unilaterally. The central instrument of this strategy is not alliances or direct military interventions but trade tariffs, used as economic sanctions and adjusted according to the level of compliance from other nations.

The first major test of this strategy has taken place precisely in Latin America, with the migration issue. Facing the U.S. threat to impose 25% tariffs on all Colombian products after Colombia banned deportation flights of migrants from the U.S., President Gustavo Petro gave in, demonstrating the deterrent power of these measures—especially since the U.S. is Colombia’s largest trading partner, purchasing about a quarter of its exports.

During the Cold War, global stability relied on the threat of nuclear weapons. Today, the main tool of U.S. coercion is unilateral tariffs, which arbitrarily impose economic costs on its trade partners and force them to make concessions under the threat of greater losses. These measures are implemented without regard for World Trade Organization (WTO) rules. The risk of this new pressure game is the escalation of retaliatory actions, where affected countries might respond with similar measures. In a context of high economic interdependence, this could lead to a kind of “mutually assured destruction” in the financial sphere, where uncontrolled trade disputes trigger a systemic collapse.

Latin America has become a testing ground for this new U.S. foreign policy, with a first major trial in the implementation of a hardline immigration policy. This strategy has exposed the asymmetric power dynamics between the U.S. and the region, revealing Trump’s vision of Latin America and the Caribbean as a territory of drugs, migrants, criminals, and “undesirables” that must be controlled. This shift marks a transition: from the indifference with which the region had been viewed, or even ignored, to its consideration as a threat, making it a focal point of concern in U.S. discourse.

The big question is whether Trump’s negative agenda for Latin America will succeed in curbing China’s influence, as the Asian giant has become a key economic player in the region, or whether, on the contrary, it will encourage stronger Latin American ties with China.

There is already speculation about a renewed version of the Monroe Doctrine, this time targeting China instead of Europe, reflecting Washington’s growing concern over Beijing’s presence in the region. Although Latin America is not the most urgent geostrategic priority for the U.S., maintaining strict control over the region remains a key condition for both American security and its global power projection. China’s influence is undeniable, especially considering that 40 Latin American and Caribbean countries have joined the Belt and Road Initiative, with the Chancay port complex in Peru inaugurated in November 2024 in the presence of President Xi Jinping.

However, the appeal of China’s Belt and Road Initiative for Latin America cannot be explained solely by the region’s infrastructure deficit, the search for new trade opportunities, or access to financing. It is also linked to the construction of an “invisible infrastructure” in the realm of ideas, which strengthens China’s soft power. Latin America’s historical admiration for the American way of life and institutions is gradually giving way to an interest in the Chinese development model, which has proven effective in eradicating hunger and promoting social inclusion.

China presents itself as an economic power capable of helping other countries develop and build a community with a shared future for humanity, promoting infrastructure projects that improve living conditions and offering global public goods. Clear examples of this strategy include Chinese investments in the energy transition, particularly in solar and wind power and electric vehicles in Brazil, which could open new avenues for sustainable development in the region. Furthermore, China positions itself as an alternative to Trump’s policies, appealing to the international community to defend multilateralism and a rules-based international order. Its discourse emphasizes the sovereignty of Latin American countries as a fundamental pillar, in contrast to the more interventionist approach of the U.S., which now explicitly emerges as the dominant strategy toward the region.

It is essential to stay vigilant because, as an African proverb says, “When elephants fight, it is the grass that suffers.” In this context of hegemonic rivalry and its repercussions on the region, Latin America must recognize its own agency and understand the urgency of its integration. The cancellation of the emergency CELAC meeting, convened at the request of the Colombian president to discuss the U.S.-imposed deportation crisis, is a troubling sign of the region’s lack of coordination in the face of these challenges.

This need for transformation becomes even more pressing when considering Latin America’s vast reserves of critical minerals, essential for the global energy transition. The region must unite to avoid falling into the colonial logic, shared by both the U.S. and China, that reduces it to a mere supplier of raw materials. These strategic minerals present a unique opportunity for Latin America to redefine its role on the global stage. However, this will only be possible if the region demands technology transfer and repositions itself in the international division of labor instead of merely exporting minerals to be processed with greater added value abroad.

It is crucial that the Chancay port does not contribute to the tragic re-primarization of our economies but instead becomes a hub for transformation. Rather than exporting only raw minerals, Latin America must produce higher-value-added goods, creating jobs and fostering sustainable local and regional development.

*Machine translation proofread by Janaína da Silva.