Mucho se habla de la necesidad de una matriz energética limpia para los países como parte de un modelo de desarrollo sostenible y libre de las emisiones de carbono. Por ello, hay mucha presión por parte de la gobernanza global para que los países asuman compromisos de bajar sus niveles de CO2. En este marco, el litio como mineral para la producción de baterías de automóviles para sustituir los coches a combustión, es cada vez más disputado en la escena internacional. Sin embargo, su extracción no es tan limpia como se anuncia y se desea. Por ello, cabe preguntarse ¿Qué tan estratégico es el litio para los países de América del Sur?

En el Norte argentino, en las provincias de Jujuy y Salta, las comunidades indígenas de la puna (Cuenca de Salinas Grandes y Laguna de Guayatayoc) todavía reclaman, luego de décadas, por los títulos de las tierras, de las cuales sufren desalojos y exclusión a pesar de los acuerdos entre el gobierno provincial y las grandes corporaciones de extracción del litio.

El acceso al territorio fue una forma de reparación histórica de los estados por el despojo que sufrieron las comunidades con la llegada de la colonización europea. Sin embargo, en la actualidad, a pesar del importante rol que juegan los pueblos originarios en el mantenimiento de la vegetación nativa y sus saberes novedosos (no científicos) para la convivencia armoniosa con el ecosistema terrestre, muchos gobiernos no respetan sus territorios y derechos.

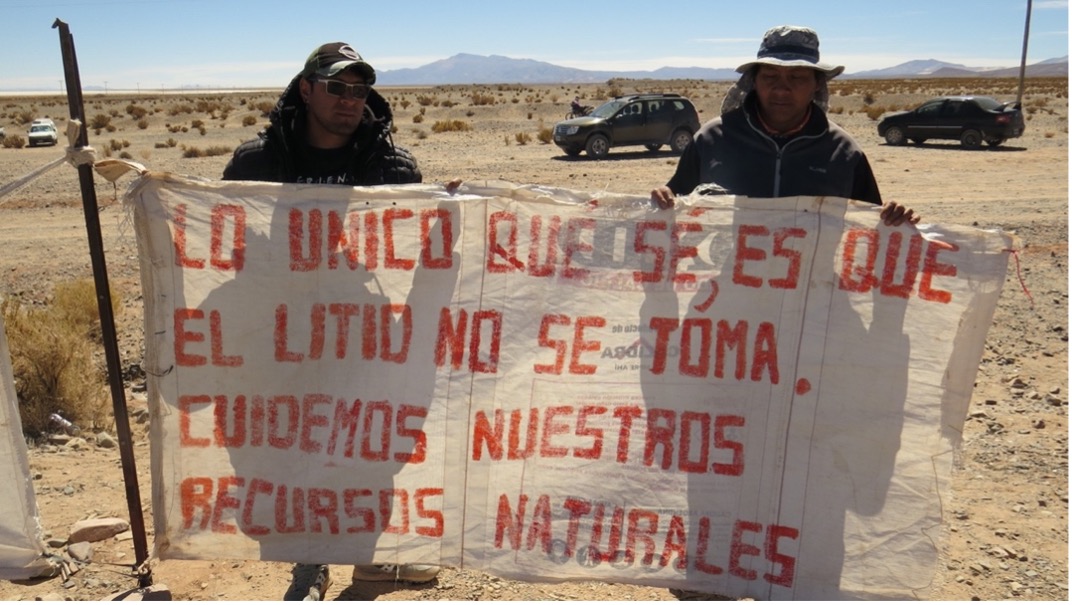

Photo de Ricardo de Carvalho Jatobá

En Argentina, como en varios otros países, estas comunidades tienen ciertos derechos garantizados en la reforma constitucional de 1994 en base al Convenio 169 de la OIT (Organización Internacional del Trabajo) que establece la consulta previa, libre e informada a los pueblos indígenas y tribales sobre el futuro de sus vidas y de sus territorios, cuando sea necesario. Este acuerdo internacional fue ratificado en 1989 junto a otros 15 países de Latinoamérica.

Pero, en la práctica, las autoridades autorizan actividades extractivas y el cultivo agrícola en los territorios indígenas sin consultas o su participación en las negociaciones. Esta es una constante entre los países latinoamericanos que siguen volcados a la exportación de productos primarios como granos y metales, debido a la demanda global, aunque ello tenga impactos ambientales y sociales a mediano y largo plazo.

La actual narrativa que promueve el uso de automóviles eléctricos en sustitución del uso de los combustibles fósiles para evitar la emisión de gases de efecto invernadero, sin embargo, es confusa y equivocada. Los automóviles eléctricos necesitan baterías que se fabrican a partir de litio, un metal muy presente en Argentina, Bolivia y Chile, países que concentran alrededor de 85% de las reservas del mundo. Pero estos tres países que hacen parte del “triángulo del litio”, en parte y con enormes diferencias, no están preparados ni para beneficiarse de la industralización, ni tampoco para mitigar los impactos negativos de su extracción.

Lo que podría ser una oportunidad para una cooperación Sur-Sur, según el anuncio de Evo Morales en el pasado, se volvió en una amenaza para los gobiernos de esos países y un nuevo despojo de los pueblos originarios. No existe la participación de las comunidades indígenas en el diseño, seguimiento y evaluación de los planes de desarrollo nacionales o provinciales, además no se logra priorizar el interés público por sobre lo privado y extranjero.

Photo de Ricardo de Carvalho Jatobá

Según Florencio, un indígena que el 2 de septiembre de 202 se manifestaba junto a la Ruta 52, en las Salinas Grandes, provincia argentina de Jujuy, la demanda de los afectados por las energías renovables no es radical. No se trata de seguir con la carbonización de la economía global o parar de producir teléfonos o automóviles eléctricos, sino de escuchar a los pueblos a quienes pertenecen esos territorios y saberes e involucrarlos en las tomas de decisiones. De esa forma, al menos las desventajas pueden ser compensadas por actividades de reducción de los daños y riesgos generados a la tierra y las comunidades.

Ese es el ‘interés nacional’ que tanto cuesta a nuestros líderes asumir en la escena política internacional. Y es que preocupa que la nueva narrativa no implique otra cosa que una repetición histórica del colonialismo y un nuevo despojo de los pueblos originarios de la región.“Primero, vinieron los Incas, después los Españoles, y ahora nuestros propios hermanos, los argentinos” – dice Florencio.

Los indígenas tienen la clave para el cambio del modelo de desarrollo de los países. Así, es importante reconocer la naturaleza política de la cuestión. Eso significa rescatar el rol de los Estados en la mediación entre mercado y sociedad, y en la planificación del desarrollo con participación de los distintos actores interesados. Esto es fundamental para no promover una transición energética que termine beneficiando únicamente a una élite global.

Por ello, debería cambiarse el adjetivo ‘limpio’ por ‘renovable’. El concepto ‘energía limpia’ confunde a la opinión pública ya que omite los problemas de la contaminación del medio ambiente, el uso intensivo del agua, los impactos en la salud de las comunidades locales indígenas y el desplazamiento de los pueblos.