Immigration is a central debate in this year’s U.S. elections. According to the International Organization for Migration (IOM), the Mexico-U.S. border is the largest migration corridor and the deadliest land migration route in the world today. Official figures show that Latin America and the Caribbean are the primary regions of origin for migrants traveling to the U.S., where an estimated 47 million migrants, including those seeking refuge, currently reside.

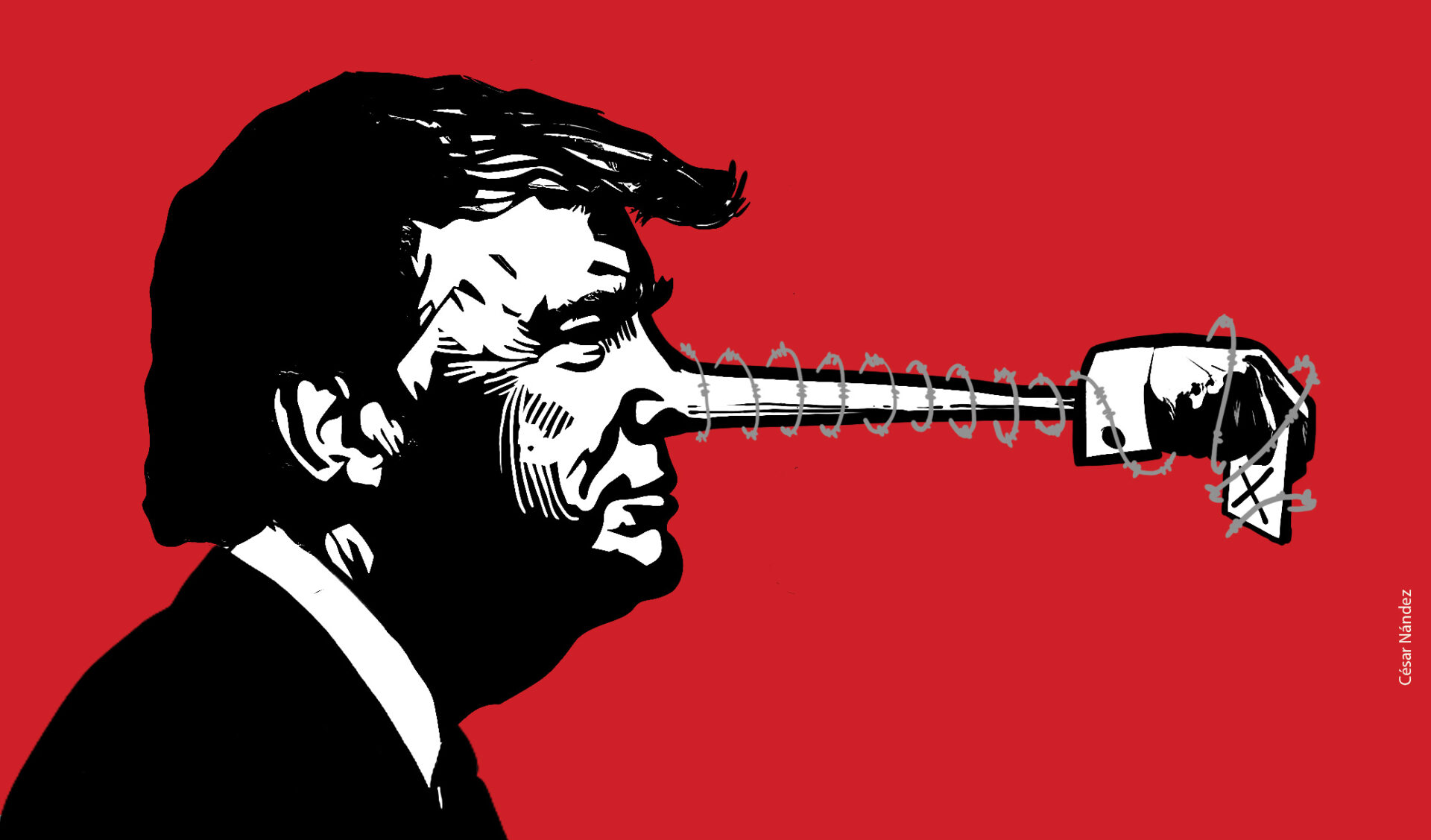

While immigration has gained increasing importance in U.S. presidential campaigns, there is also a growing, systematic fabrication of misinformation designed to confuse and divide society, particularly to discriminate against undocumented migrant workers and their families.

In this context, we can analyze the electoral strategy publicly promoted by segments of the media and political representatives to create the false notion that migrants are responsible for rising “crime” rates.

The use of this electoral strategy has been central to the campaigns of far-right parties not only in the U.S., but also in Europe (for example, Le Pen’s party in France, Fratelli d’Italia, which elected Giorgia Meloni, Vox in Spain, and Chega in Portugal).

During Republican Party conventions, Donald Trump repeatedly tries to convince voters of the false notion that the entry of undocumented immigrants is linked to an increase in violence in major U.S. cities. As a solution, Trump and his party insist on building a wall “paid for by Mexicans” and implementing a zero-tolerance policy to ban, criminalize, and deport millions of migrants.

The “migrant crime” myth and its impact

On July 18, The New York Times published an article titled The Myth of Migrant Crime, which provides data and information disproving the alleged connection between rising immigration and crime. According to the article, the current Republican candidate coined the term “migrant crime,” which has been repeated in his campaign rallies for the White House.

The idea of migrant crime is rooted in a false, xenophobic thesis—a lie designed to paint migrants as “dangerous people,” a strategy used by dominant elites since colonial times to oppress and strip rights from marginalized and racialized non-white populations.

A similar strategy was employed in the early 20th century during the rise of the Nazis and fascists in Europe. By spreading antisemitic myths, Adolf Hitler’s concept of the “big lie” convinced German society that Jews were responsible for the defeat in World War I and the economic crisis, ultimately leading to the Holocaust, which affected Jews, homosexuals, and racialized non-white people.

While these events took place in different historical contexts, there are significant parallels in how far-right groups manipulate mass disinformation, both then and now. Just minutes before the June 13 attack in Pennsylvania, Trump—who had already accused immigrants of “poisoning the country’s blood”—gave a hate speech against immigrants.

However, this is not just rhetoric to mobilize white supremacists and so-called nativists. On an ideological level, the government proposal endorsed by the Republican campaign advocates for the “largest mass deportation in U.S. history”: up to 20 million undocumented people starting in 2025, with assistance from the military.

The effects of these hate-driven speeches and policies are well-documented. In addition to deadly migration routes, they lead to mass arbitrary detentions—including children separated from their families—record numbers of disappearances and deaths at borders (especially on routes like the Darién Gap in Panama), torture, rape (especially of women and children), and the creation of new routes for forced labor and human trafficking.

The scapegoating of migration in U.S. electoral disputes

The fabrication of lies that scapegoat migration for social ills aims to distort the fact that migrant labor in the U.S. significantly contributes to economic growth, particularly in sectors like agriculture, construction, healthcare, technology, and services.

Among migrant populations risking their lives for better socioeconomic conditions in the U.S.—coming not only from Latin America and the Caribbean but also from Asia, the Middle East, and Africa—the presence of women and children is increasingly common. The recent documentary Lo Que Queda en el Camino (What Remains On the Way), a winner of international awards, is a powerful record of the massive presence of women and children in the so-called “Migrant Caravans.”

For those who manage to enter the country without documentation, the destination is often the most precarious jobs (those locals do not want to do), which are highly profitable for employers and the state since it is work without any rights.

Despite being a vital part of the economy, they do not have the right to vote, and the U.S. continues to invest heavily in militarizing and externalizing its borders, making it more challenging to regularize migration or even apply for asylum. Simultaneously, political forces push disinformation and hate speech against immigrants, which can cause catastrophic societal damage, as seen in critical historical events and recently in the United Kingdom.

In this context, media outlets and political groups that support democracy play a vital role in combating disinformation and enhancing the debate on social and political issues, especially those related to the structural causes of migration, wars, and inequalities that drive most displacement—causes in which U.S. policy plays a significant role. While migration continues to be unjustly blamed for social problems, deepening the migration debate in the current U.S. electoral contest, now with Kamala Harris as a central figure, will be crucial not only for migrants but also for the geopolitical disputes surrounding borders and global mobility.