Venezuela is a dictatorship where elections are still held. But these do not serve to represent the interests of the population or to understand their preferences. Today, the vote is a tool used to destroy citizens’ autonomy, confuse the electorate, and fragment the opposition.

The main goal of this institutional engineering is the deliberate destruction of the party system. Modern societies face significant challenges in organizing collective action without political parties. A lack of time, experience, resources, and the vast distances involved prevent the majority of the population from organizing to fight for their demands. Dictators know this, which is why they work to neutralize political parties. When parties are absent, citizens’ political activity often becomes leaderless, disoriented, and powerless.

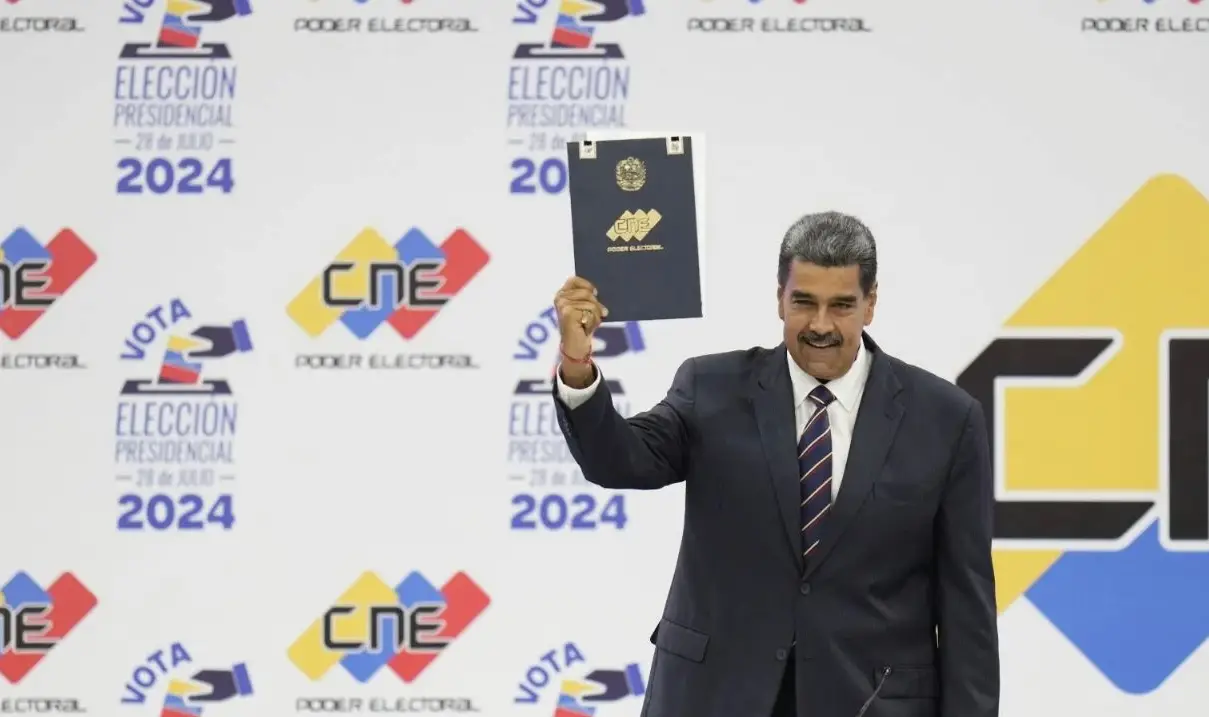

The new party system, designed by Nicolás Maduro’s authoritarian regime, places the PSUV (United Socialist Party of Venezuela) at its center. It controls all branches of the state, yet it has completely lost popular legitimacy. Available data, such as the records from the July 28, 2024 presidential election, indicate that the ruling party barely garners around 20% real support — and without access to state resources, this figure would likely be even lower.

In contrast, the opposition to Maduro holds the support of 80% of the electorate, but it consists of a myriad of parties that seem to change with each election, with most of the population barely aware of who they are. Worse still, many parties that label themselves as opposition often lack any political track record or visible social base, and are mostly seen as collaborators of the regime or as mechanisms to divide the opposition vote.

This proliferation of parties is not a sign of democratic vitality, but rather of its suppression. The fragmentation of the opposition does not reflect a diversity of proposals, but a power architecture designed to block any effective aggregation of demands.

The most recent parliamentary elections clearly show how this ecosystem works. The main opposition platforms are excluded through unconstitutional means, and their most popular leaders are jailed or forced into exile. Even minor but independent parties, like Movimiento Por Venezuela (MPV), were disqualified without explanation.

This does not only affect the traditional opposition. A large number of leftist parties and movements that once allied with Chávez but now oppose Maduro have lost all political representation, and their leaders live under constant police pressure or face disappearance. The hijacking of the electoral card of the Communist Party of Venezuela, the persecution of former mayor Juan Barreto, and the recent imprisonment of former minister Rodrigo Cabezas are clear examples.

Moreover, the opacity of Venezuela’s electoral system is such that it is impossible to know how many votes any organization received. This lack of transparency allows Maduro to reward political actors by distributing seats in the National Assembly to those who demonstrate loyalty to the system.

This scheme has proven successful. The result is massive voter abstention and widespread public disinterest in political activity, as people fail to see any tangible results for their needs. Meanwhile, the opposition remains divided between groups willing to accept a subordinate role in exchange for some resources and state recognition, and others who, in the absence of institutional mechanisms, appear to be waiting for foreign intervention to shift the balance of power. The result is total political paralysis.

During the 1980s and 1990s, Venezuela was criticized for its “cogollos” democracy (party oligarchies). Today, the country lives under a “latifundista” dictatorship, economically based on unproductive territorial control and politically on repression and the distribution of rewards to its “peons.”

The democratic opposition does not merely face the challenge of channeling fragmented social demands: it also contends with a punitive legal framework designed to prevent its consolidation. Instead of growing stronger through electoral experience, opposition parties are dismantled again and again by administrative decisions with no legal basis.

In this reality, Venezuelan parties face a monumental task: to reinvent themselves under conditions of secrecy, repression, and total institutional control. So-called “mass parties” are effective in democratic contexts, with free access to mass media and stable rules. But their diffuse ideologies and traditional organizational structures are ineffective under constant persecution and institutional harassment.

Difficult as it may seem, only by returning to their social roots, rebuilding organic ties with the citizenry, and embracing creative forms of organization and resistance can parties preserve their fundamental democratic role: to serve as legitimate and effective channels of political representation. Counterintuitive as it may be, political parties must stop measuring their success in electoral results and begin to evaluate it in terms of organizational capacity and committed leadership.

This is not only essential to sustain democratic resistance in the present. In a potential scenario of political transition, the outcome will only be truly democratic if there are strong parties with social legitimacy and organizational capacity, capable of guiding the process and preventing the emergence of a new disorder or another form of authoritarianism.

In a system where elections are no longer mechanisms for alternation, but for authoritarian consolidation, the greatest challenge is to resist as a party — when everything is designed to prevent it.

*Machine translation proofread by Janaína da Silva