Once upon a time, there was a democratic Cuba where political parties decided their competition in free elections, where citizens elected their representatives in a context of freedom. This period was short-lived, but it existed. It lasted for a little more than a decade. The problem is that the official single discourse has buried its historical record and the oral transmission, after seven decades, has become extinct. The surprising thing is that that exceptional period also produced a Constitution in 1940 that expressed in its first article its republican stamp by stating that it was “an independent and sovereign State, organized as a unitary and democratic Republic, for the enjoyment of political freedom, social justice, individual and collective welfare and human solidarity“.

March 10 marks the 70th anniversary of the rupture of the democratic order in Cuba. This does not mean that since its independence the island has enjoyed uninterrupted democracy. On the contrary, the only democratic period in Cuba was very brief, from 1940 to 1952. Historian Carlos Manuel Rodríguez Arechavaleta has immersed himself in that period to give explain the dynamics of electoral competition.

In his book “The Republican Democracy in Cuba 1940-1952”, he gives an explanation of the party system of that time that contrasts with the current single-party regime. He also emphasizes that the incentives presented by the political system for multipartyism made radical parties, such as the Communist Party, entered into a logic of electoral competition, which made it an inclusive political system. Unfortunately, the result of this is that Cuba has lived most of its history under authoritarian regimes and this marks an absence of democratic culture.

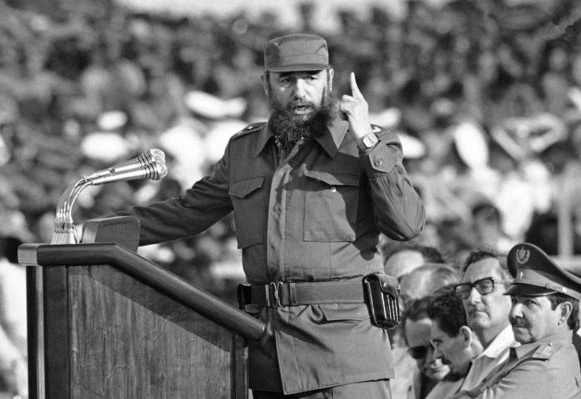

Both Fidel Castro’s discourse and that of the current elite of the Communist Party of Cuba have tried to ignore the fact that there were great efforts to promote democratizing reforms in Cuba, and that there was in fact a period in which a plural democracy prevailed with competitive elections between political forces as diverse as communists, socialists, liberals, conservatives, and reformists.

This is very well described by Loris Zanatta in his book “Fidel Castro, the last Catholic King”. There is a young Fidel Castro with a marked anti-political discourse, who contemptuously questioned the Cuban democracy of that time, which he classified as a “partycracy”. With the permanent discursive use of the term “politicking”, he challenged the consensual and dialogue dimension of politics, which gave rise to a coincidence with the discourse that Batista later had in the lobby of the coup.

This democratic period was original even in the region. Let us only remember that in the Dominican Republic Rafael Trujillo ruled, in Nicaragua Anastasio Somoza García, and in El Salvador, in 1948, a military coup put an end to the government of another military man. In Cuba, on the other hand, everything indicated that its colonial history and American tutelage had been left behind when the local political forces held a Constituent Assembly that would provide the legal framework for the holding of several presidential and legislative elections in which power would alternate, at least until 1952.

In fact, Fulgencio Batista, who with the 1952 coup would put an end to the Cuban democratic period, had been elected under the Constitution in 1940. He would be followed by Ramón Grau San Martín (1944) and Carlos Prío Socarrás (1948). In the elections of this period, electoral participation was increasing, from 73 to 78 percent.

The so-called “October Constitution” established that the presidential election was indirect, through the electoral college, and a relative majority was enough (like most of the countries in the region at that time, there was no second round). However, in 1943, through a new Electoral Code, the direct election of the president was established.

The democratic period would end on March 10, 1952, when Batista, campaigning for the presidential elections to be held that year, seeing very little chance of coming to power in a democratic manner, used his military influences to close the constitutional order.

The Cuban people would never again know a democratic regime, since after Batista’s coup came the longest totalitarian experience in the region, embodied first by Fidel Castro and then by his brother Raúl. Today, it is President Miguel Díaz Canel who inherited the responsibility of preventing Cubans from freely electing their representatives.

To the surprise of international public opinion and of the regime itself, on July 11, 2021, a multitude took to the streets to demand freedom and democracy. Their anthem was “Patria y Vida” (Homeland and Life). The repression was immediate, today Cuba’s jails are full of political prisoners, activists such as the artist Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara, or politicians such as Daniel Ferrer are still detained. There are trials and convictions of minors and persecution of journalists, especially women, as shown in the case of Luz Escobar.

Perhaps Cuba’s youth has mobilized without knowing this democratic interregnum, however, its emergence should be interpreted as a line of continuity in Cuba’s democratic tradition, a tradition that seeks to be deployed despite the shared contestation between Batista and the Castros.

Translated from Spanish by Janaína Ruviaro da Silva