The dominionist movement promotes the construction of Christian nations through the occupation of key institutions in society, as a way to prepare for the “second coming” of Jesus. Grounded in the belief that the world is engaged in a spiritual battle between “good” and “evil,” it mobilizes churches and religious leaders to act in the political–institutional arena with the aim of expanding their moral agendas and imposing their religious values on society.

Dominion theology is linked to a concept of the family as the pillar of society — a space where religious values are passed down from generation to generation, based on the union between man and woman (Genesis 2:24) for the purposes of love, procreation, and the upbringing of children (Ephesians 6:4). In this theology, morality is an immutable system revealed by God and transmitted by religious leaders. This system also serves as a mechanism of social control over sexuality, the body, and family structures. Dominionism is a form of political–religious activism that seeks to “reclaim” society for God through the strategic occupation of institutions.

Dominionists believe that Christians have the duty to dominate the seven spheres of society (family, education, media, politics, economy, arts, and religion) to establish God’s Kingdom on Earth. The dominionist vision is postmillennial: before the “second coming” of Christ, Christians must restore biblical morality and establish a social order based on Gospel values. This justifies the political engagement of Pentecostals, who present themselves as spiritual soldiers in the fight against “evil,” represented by ideas such as feminism, LGBTQIA+ rights, communism, and secularism. Politics becomes a spiritual battlefield, where the goal is not to negotiate but to defeat the enemy.

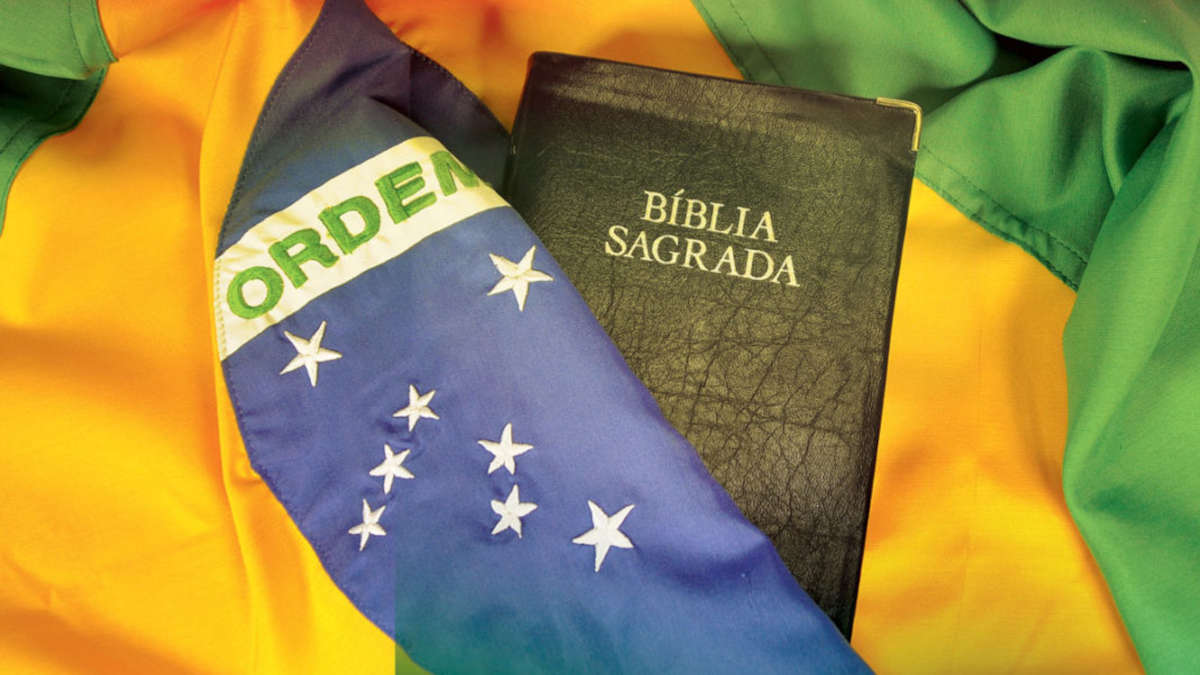

This religious configuration took hold in Brazil with the election of President Bolsonaro in 2018, supported by Pentecostal denominations such as the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God and the Assemblies of God. His government incorporated religious leaders into strategic ministries and promoted an alliance between conservative Christianity and an authoritarian political project. The phenomenon, understood as Christofascism, establishes a form of fundamentalism that instrumentalizes faith to legitimize authoritarianism, hierarchy, and intolerance.

Dominionism uses politics to shape public opinion and secure voter support, promoting legislation that reflects its values and moral conceptions. One of the main actors in these culture wars is federal congressman Nikolas Ferreira (PL-MG), the most voted candidate in 2022. Aligned with dominionism, he is the author of the book O cristão e a política: descubra como vencer a guerra cultural (2023), in which he calls on Christians to fight against communism, feminism, “gender ideology,” and LGBTQIA+ rights.

The aggressive yet charismatic language of this radical leader makes him a central figure in political–religious action. His rise represents the consolidation of a new generation of evangelical politicians — media-savvy, combative, and ideologically aligned with the far right. His discourse reinforces thematic polarization and contributes to the advance of an authoritarian agenda that jeopardizes the pillars of the democratic rule of law.

Regarding same-sex unions, research shows that although the Supreme Court (STF) recognized this right in 2011, conservative lawmakers have sought to overturn this achievement with bills such as PL 5167/09, which aims to prohibit legal recognition. Other bills seek to amend the Civil Code to restrict the notion of family to the union between a biological man and woman. In response, progressive sectors have proposed initiatives to consolidate LGBTQIA+ couples’ rights into ordinary legislation, but these face strong resistance.

In the area of abortion, most of the bills analyzed aim to further restrict access to the procedure — even in cases where it is already legal. The rhetoric is based on religious principles such as the defense of life from conception, and the argument that abortion is a form of state-sanctioned murder. Feminist movements and human rights organizations, on the other hand, defend decriminalization as a matter of public health, equity, and women’s autonomy.

Education is another fiercely disputed arena. The “School Without Party” project, defended by dominionist lawmakers, seeks to remove discussions of gender, sexuality, and human rights from classrooms. Schools are portrayed as spaces of “ideological indoctrination” that need to be reclaimed to “protect children” and “family values.” In practice, the project would restrict academic freedom and impose a conservative religious vision on school curricula.

The far right in Brazil defends values such as the traditional nuclear family according to biblical precepts and religious morality, and rejects ideas like gender equality, diversity, and social inclusion. Pentecostal groups are aligned with this ideology, envisioning a limited state guided by God and above the law. Politically, Pentecostals have allied with the far right, serving as a pillar of support for these culture wars in Brazil. Churches — especially neo-Pentecostal evangelical associations — have provided politicians with a broad social base. The expansion of Pentecostal evangelical religious activism is evident in the legislative proposals presented between 2018 and 2024.

These agendas have included the criminalization of education and reproductive rights, among others, all perceived as violations of human rights. Religious leaders aligned with the prosperity gospel and dominion theology have also gained media prominence, hijacking the moral and watchdog agenda to stir engagement, monetization, and religious adherence on social media. The Brazilian judiciary has become an important counterweight to check conservative advances, but it has also become a target of criticism and threats from the far right, which seeks to curb its powers and sway public opinion against it.Ultimately, moralizing politics based on exclusionary religious values puts pluralism and the secular nature of the state at risk. Dominion theology, by transforming legitimate political disputes into spiritual battles between good and evil, eliminates space for dialogue, negotiation, and the recognition of diversity. The advance of this model threatens democracy, especially as it instrumentalizes faith to legitimize the exclusion of minorities and the criminalization of fundamental rights.

*Machine translation, proofread by Ricardo Aceves.