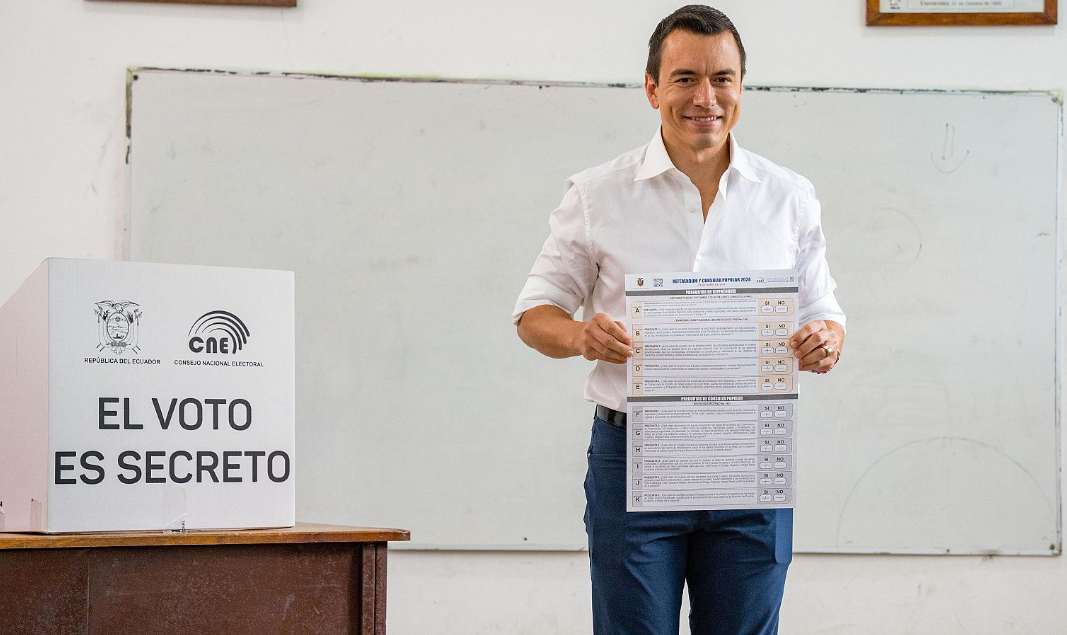

The issue of public financing for political parties has entered Ecuador’s political debate following President Daniel Noboa’s proposal to eliminate it, for which he has called a popular referendum on November 16.

Political parties are essential actors for the existence and consolidation of modern democracies. Their role in articulating interests, representing citizens, and competing for political power has been widely recognized in political theory. However, their functioning depends largely on how they are financed.

The origin of the resources sustaining their activity determines not only their independence but also their legitimacy before society. In contexts where private financing predominates, the system becomes vulnerable to capture by economic groups or even organized crime.

Therefore, public financing is not a concession but an indispensable tool for ensuring the integrity of the democratic system.

The democratic function of political parties

Political parties can be understood as organizations oriented toward the pursuit of political power through citizen mobilization and support. In addition to articulating social demands, these organizations play a central role in structuring political competition, influencing the configuration of the party system within a democracy. In contemporary contexts, it has been noted that many parties tend to depend heavily on state resources, acting as intermediaries between society and public institutions—thereby reinforcing their presence in the political and administrative playing field.

From this perspective, parties are fundamental mediators between the state and society. However, when their financing depends on unregulated private sources, this relationship becomes distorted: parties cease to respond to their bases and electorate, serving instead their financiers and their interests. In the worst cases, the entry of illicit funds from drug trafficking or other criminal activities undermines the autonomy of democratic institutions and threatens governance.

Public financing as a guarantee of autonomy and equity

Public financing of political parties tends to guarantee minimum conditions of equality and reduce dependence on private sources. State support should be understood as an “investment in democracy,” aimed at strengthening fair competition, transparency, accountability, and, of course, the parties’ connection with their potential voters. This type of financing also contributes to party institutionalization, understood as the parties’ ability to maintain stability, legitimacy, and social rootedness.

It is clear that the provision of public resources promotes political pluralism, especially in contexts where economic inequalities could exclude emerging movements or parties with sound, programmatic ideas but lacking financial means. However, this also poses a challenge of similar magnitude and complexity: state financing must be accompanied by robust systems of oversight and auditing to prevent clientelistic use (especially by ruling parties) or diversion of funds for personal or irregular electoral purposes. Transparency is an indispensable condition for citizens to perceive these resources as a public good in service of democracy, rather than as an unnecessary expense, as it is often popularly viewed.

The Ecuadorian case: fragmentation and weakness of the party system

Ecuador’s party system has historically been fragmented, volatile, and weakly institutionalized. Since the return to democracy in 1979, the country has witnessed a proliferation of political organizations with little continuity or territorial representation. According to data from the National Electoral Council and the National Assembly, for the 2024–2025 period there are more than 200 registered political organizations—including parties, national movements, and local movements—of which only four organizations and a few provincial movements have legislative representation. This translates not only into an overwhelming number of ideological alternatives but also into depersonalized politics and low credibility.

This fragmentation generates problems of governance and representation, as it makes the formation of stable majorities in the legislature difficult and fosters the personalization of politics (the so-called “isms” so recurrent in our history). The result is evident: excessively fragmented systems tend to produce instability, as parties lose their function of channeling coherent interests and become vehicles for circumstantial leaderships, or, in turn, encourage political defections.

The institutional weakness of Ecuadorian parties is also reflected in their lack of solid internal structures, clear ideological programs, and mechanisms of accountability. This has led many parties to depend on informal financing or clientelistic networks, exposing them to the influence of economic groups or even illicit actors. In this context, public financing represents a fundamental tool to reduce dependence on private resources, promote transparency in political activity, and ensure autonomy from private or illicit interests.

The cost of politics and the value of democracy

President Daniel Noboa’s government has promoted a popular referendum for November 16 with the objective of eliminating public financing for political parties, reducing the number of legislators, and convening a constituent assembly. The president’s argument for this measure is to redirect those funds—approximately USD 4 million annually—toward “larger-impact areas” such as health, education, and security, among others.

According to polling by Clima Social, the “yes” vote would prevail on questions related to eliminating financing for political parties (52%), reducing the number of legislators (66%), and convening a constituent assembly to draft a new constitution (48%). Taken together, the tentative results reflect a climate of discontent with the foundations of the political system, its institutions, and a significant—though cautious—willingness toward deeper transformations such as drafting a new constitution.

While reducing or eliminating this financing aims to relieve public spending and demand greater responsibility from parties, the measure could produce the adverse effects already discussed: increased dependence on private money and, consequently, greater risk of party capture by powerful economic groups or infiltration by criminal organizations.

In a party system as fragmented and weakly institutionalized as Ecuador’s, withdrawing state support without strengthening oversight mechanisms would deepen the crisis of representation even further. Therefore, rather than eliminating the fund for party resources, the challenge lies in making its use transparent and punishing abuses—ensuring that political financing serves the public interest and strengthens representation. Ultimately, investing in regulated and audited public financing means investing in democracy.