Panama, with its little more than four million inhabitants and a mere 75,000 square kilometers of surface area, made international news during the pandemic. Unwillingly, it did so because at different times its health performance has been among the worst in the world, and the impact of the pandemic on its economy has been the most devastating. Thus, world public opinion seems to look with astonishment at what Panamanian citizens know well: the country is full of contradictions and there seems to be no middle ground.

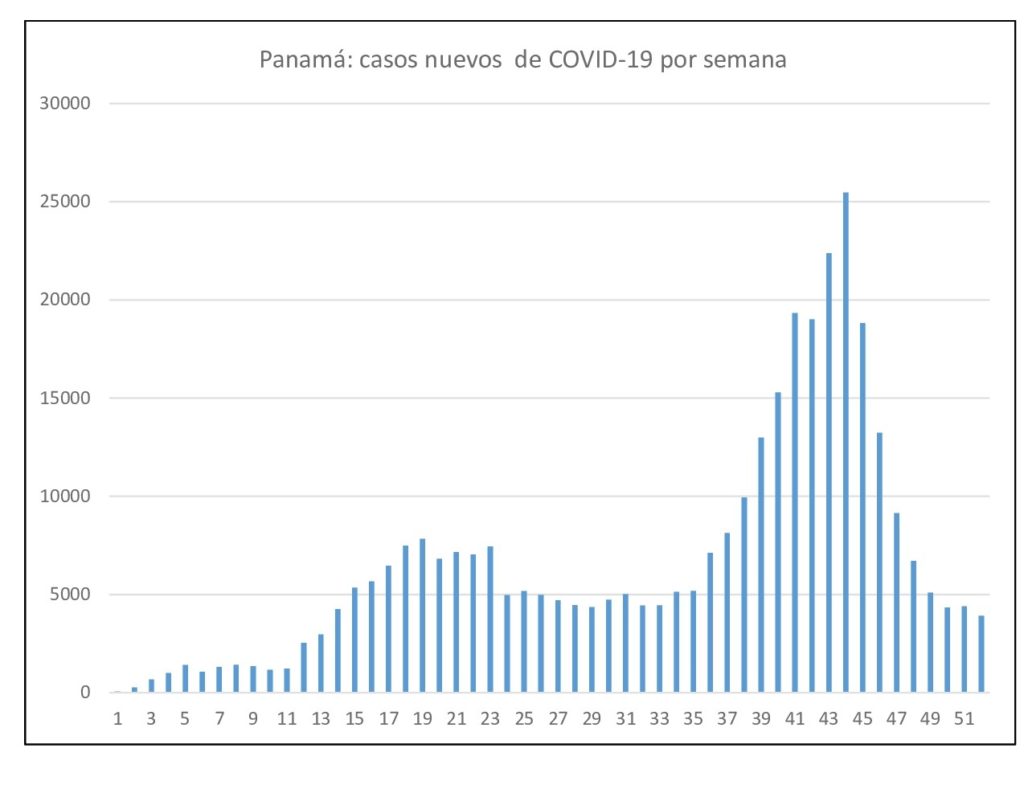

“Objectively”, at the beginning of July Panama was the Latin American country with the most reported cases per 100,000 inhabitants. Above Brazil, for example, which is reported to have been intentionally infecting its population, which is not the case of Panama at all or Costa Rica, a neighboring country with similar dimensions and economic possibilities. The months of July and August last year paled in comparison to the avalanche of cases in the second wave of December and January.

Source: Ministry of Health.

Why did this happen? Naturally, the search for explanations in Panamanian society is taking place in the political sphere, where subjectivity reigns and narratives are the product of the interests and repertoires of the different political actors. There have been two dominant explanations in dispute, but which sometimes overlap: one based on the country’s historical-institutional trajectory and the other emphasizing structural inequality.

The historical-institutional trajectory argument

The starting point of this explanation would be the weakness of the Panamanian rule of law, which would be expressed in the clientelist nature of an obese public administration, hopelessly inefficient and with an unstoppable propensity for influence peddling and corruption. This would also explain why decision-makers are generally recruited from among the most incompetent people in the country.

This diagnosis has been articulated or promoted mainly by currents of opinion with militant libertarian thinking or by adhesion, which, although they are in the minority, have an increasingly developed hegemonic vocation.

. Their proposal for managing the pandemic has been to move from a collective management model to one based on individual responsibility, promoted with the use of slogans such as “you stop the virus”. His proposal for financing the country’s response to the pandemic has been austerity, mainly through the reduction of civil servants’ salaries, also justified as a gesture of solidarity with those who lost their jobs in the private sector.

An important piece of his political logic has been to divide Panamanian society explanatorily into two parts: a working, defenseless and abused citizenry, facing a government representing a corrupt political elite that tends to be authoritarian. This authoritarian characterization is important because it takes the Panamanian citizenry back to one of its archetypal conflicts and, therefore, with great mobilizing capacity: that of the crisis of the late 1980s, when the Civilist Crusade – a national movement composed of civic, business and professional organizations, among others – confronted the authoritarian regime of which the current governing party, the PRD, was a part.

Institutionally, those inclined to this explanation have been very concerned about the legislative activity during the pandemic, not only because of its evident errors, but also because ideologically they consider it to be the worst expression of interventionist statism. In this sense, a fraction of the actors who promote this current of opinion have recently launched an initiative that would lead to install a parallel constituent assembly, still without explicit proposals, but with a clear destituteness and symbolically redemptive objective.

The structural inequality argument

Those who defend this idea base their explanation on the country’s social, political and economic inequality. The central argument is that, although Panama has had high – and sometimes very high – rates of economic growth in the last fifteen years, the great wealth generated by Panamanian society has not been directed to strengthening the public provision of basic services such as health, education and housing.

To the socioeconomic inequality, they add the unequal access to power that would be achieved through the financing of electoral campaigns, which tilts decisions in favor of private commercial interests or those linked to the provision of these services that should be public. According to this explanation, it is in this way that commercial openings, which proved to be inopportune, are justified and the majority of people are abandoned to their fate, or to an irregular and insufficient provision of government aid.

It is argued that this context generated conditions that worsened the epidemiological situation. First, the impossibility of informal workers -about 50% of economically active people- to confine themselves to their homes because they are obliged to work. Second, the poor housing conditions of many families made confinement unbearable. And third, the deep digital divide made it impossible for thousands of children to continue the virtual educational process with the minimum acceptable standards.

This explanation has been articulated mainly by unions, university professors, statist intellectuals and leftist youth. However, so far they have not convincingly articulated an economic proposal for the financing of the response to the pandemic, except for timid ideas about an emergency tax on large fortunes or the recurrent denunciation of the non-existence of an economic reactivation plan.

The absence of a plan has been part of the characterization of the government as neoliberal and co-opted by particular interests. Although they try, they have had difficulty convincing the population that the economic and political elites are united by common interests.

Quite possibly, the “objective” diagnosis -if such a thing were possible- would share aspects of both explanations. Politically, it is important to verify the plausibility that the population gives to these general versions of the situation, since the positioning achieved by the actors through their ideas will be fundamental to foresee the characteristics of post-pandemic Panama.

Translation from Spanish by Destiny Harrison-Griffin

Photo by Red Cross Esp on Foter.com