Roberto Mangabeira Unger, a Brazilian philosopher and thinker, has been insisting, from his position at the University of Harvard, without having many repercussions in Brazil, that “the fundamental problem in our country is not inequality — although this is a big problem — but mediocrity”. “We have the tools to get out of mediocrity, but we do not have the project,” says the eminent thinker. Looking more closely at the evolution of our presidentialism, we see that mediocrity is its ethos, as well as its modus operandi.

Ever since the Workers’ Party (PT) came to power, trying to reconcile its historic class strategy with the welfare strategy — where the revolution was restricted to three meals on the worker’s table — it discovered the formula for political consensus in the Bolsa Família Program, where social transformation no longer needed any effective change in the dominant order, as was previously supposed in the Zero Hunger Program. All that was needed was to “put the poor on the budget”, maintaining historical privileges in the name of governability, so that the miracle of multiplying votes would occur; naturally preserving the engaged and radical rhetoric.

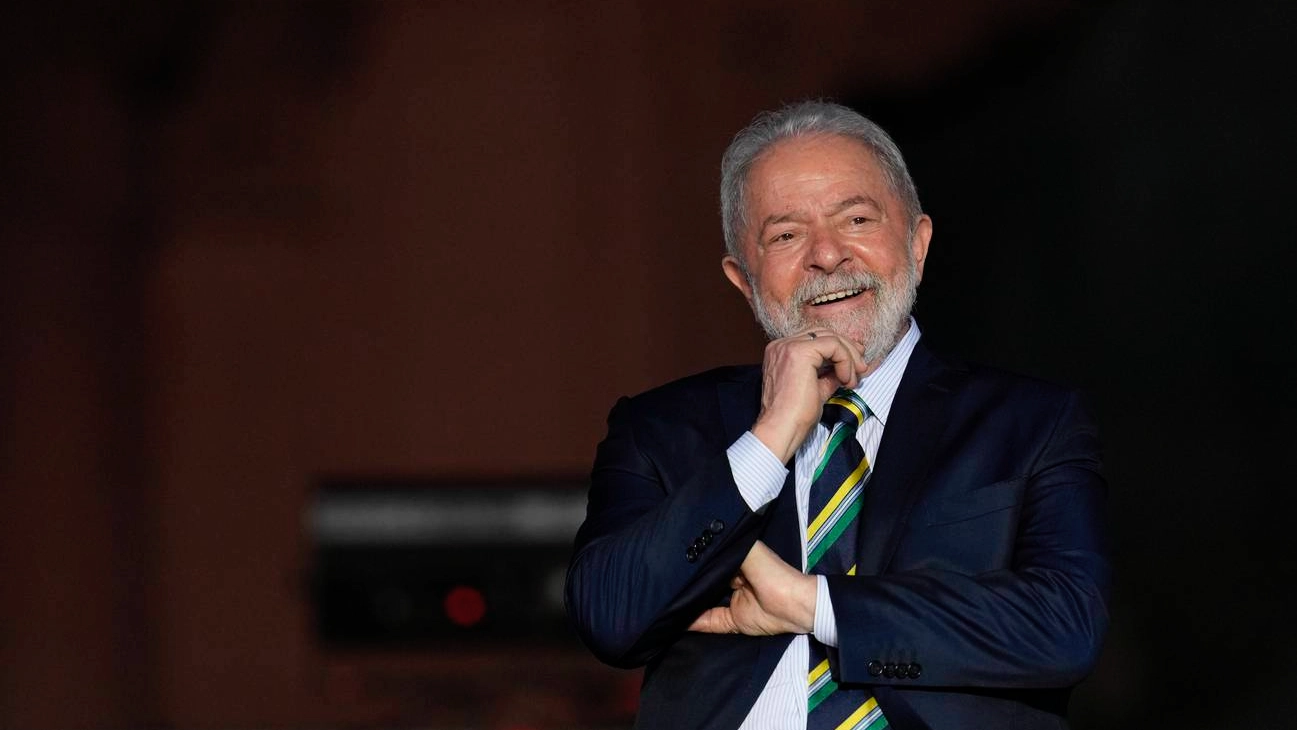

The stupendous political-electoral success of the formula made it “the maximum program” of Lulopetismo, without the left-wing parties ceasing to consider it “the minimum program”. While Lula shouted from the podiums to international applause, that the great task of his terms would be to bring three meals to the table of the poor, the PT left used political alchemy to leverage political polarization (“us and them”) searching for the “popular government.”

Everything seemed to be going well until a popular uprising in 2013 and a misrule (Dilma) paved the way for another impeachment (2016) and a power vacuum that the democratic center couldn’t occupy for many reasons that do not fit in this text. Temer’s interim government was unable to prevent society’s turning to the right, which Bolsonaro resolutely challenged.

The Worker’s Party’s return to power under the guise of a “broad front”, taking advantage of the usual impotence of the democratic center in its political-intellectual entropy, was inevitable. But such a front only paved the way for yet another Lulopetista government and its historic unpreparedness to face up to the great national challenges, despite its strong popular appeal. A paradox that reinforces and renews the pact of mediocrity.

The problem with the once unbeatable formula is that the welfare strategy has been losing social traction among the working classes, who are increasingly searching for a better place in the job market and are heavily influenced by evangelical churches that advocate the individualism of “prosperity theology”. The idea of people being dependent on the “Lord State” remained prevalent only in the Northeast of Brazil — not by chance a bastion of the old patrimonial traditions. The PT put down its new roots there, hoping to revive the old “worker-peasant” alliance. However, this formula has lost appeal among the urban proletariat, which seems to have lost faith in any progress along the path of “equality in poverty”.

The Centrão (big political center), in turn, following the failure of Bolsonaro and the programmatic flexibility of the political parties, has consolidated its leading role. Under the leadership of the president of the Chamber of Deputies, Arthur Lira, the Centrão has ceased to be a mere business counter and has become a true “moderating party”, willing to support the government on duty through positions, but now without giving up its liberal-patrimonial worldview, which is therefore mediocre.

This has not prevented rationalizing structural reforms from being implemented under the leadership of Economy Minister Fernando Haddad. The problem is that on this path he is constantly being harassed by the most left-wing sectors of the PT itself, making the government’s life even more difficult and at the whim of the Centrão.

The possibility of Brazil’s democratic development has so far come up against political nullities, capable of producing strong social mobilization, but incapable of assuming a leading role. That is to say, not able to lead the country toward economic and social emancipation. It was hoped that the Lula III government, after the Bolsonaro misrule, would function as a buffer government on the way to this emancipation. Nonetheless, its demagogic tendencies amid the absence of alternative leaders could jeopardize the task, as has also happened with Michel Temer’s interim government.

The PT has no positive leadership role within or outside the current government. On the contrary, it feeds the tearing apart of the broad front that supports it, hoping to exercise a hegemony restricted to its members.

The Brazilian left, marked by mediocrity and obsessed with the past, which it has never understood, balances itself on the vain expectation of a utopian transformation. The democratic reconstruction of the country, however, requires clarity, critical capability, and courage from political and social leaders. These qualities are rarely seen among many of Brazil’s current leaders.

We can only hope that the difficult times ahead will awaken well-equipped spirits, in the situation and opposition, capable of rediscovering the path of development amid the new possibilities and challenges of international reconfiguration, whose horizon is ominous.

*Translated by Janaína Ruviaro da Silva from the original in Portuguese.