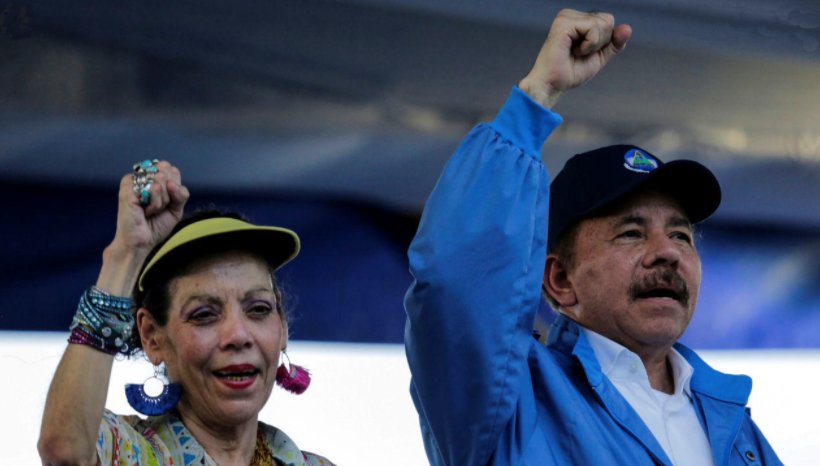

The Nicaraguan government – controlled by President Daniel Ortega, Vice President and First Lady Rosario Murillo, and their Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional (FSLN) party – is using new laws to arrest political rivals and harass independent media ahead of November’s scheduled elections. In the past month, the government has arrested five leading opposition presidential contenders, the leaders of the dissident Sandinista party Unamos, and several civil society and business leaders.

While cracking down domestically, the government is seeking international negotiations, likely over removing targeted sanctions on government officials and Ortega-Murillo family members. Crushing domestic dissent has been easy, but winning international concessions is unlikely to succeed.

Repression and detention of opposition members

Without real evidence for their charges of treason and cybercrimes, the government is engaging in stunts, releasing faked documents to supposedly implicate media outlets, civil society groups, and the presidential candidates in a coup conspiracy. The government claimed 2018’s protests were a foreign-sponsored coup attempt. Now Ortega and Murillo, despite firmly controlling state institutions and the security forces, are trying to convince followers that the “golpistas” are conspiring again, aided by the US and “other imperialist powers.”

Domestically, Ortega and Murillo are clearing away major potential opposition candidates ahead of the elections and reasserting their control of the country. They are also demonstrating their impunity and ability to threaten anyone, even people from famous families, like presidential candidate Cristiana Chamorro and former first lady María Fernanda Flores, or Sandinista icons like Dora María Téllez and Hugo Torres.

Tension and fear have increased again among the opposition and their path forward is unclear. Any candidate on the ballot in November will likely be suspected of cooptation or considered the government’s ‘chosen’ opposition. Many business leaders are keeping quiet, afraid of losing profits or assets. Banpro bank responded timidly to the arrest of Luis Rivas, its executive director.

Political strategies and United States responses

Politics, though, is always a two-level game: national governments act with both domestic and international audiences in mind. In Nicaragua, government propagandist and journalist William Grigsby has revealed the Ortega-Murillo game plan over the past month, first threatening more arrests after the initial detentions of presidential candidates. Then, after the Unamos arrests, Grigsby stated that the government was seeking negotiations with the US.

Government news platform El 19 Digital also republished a pro-Ortega Italian column claiming that “if there were a need to find a solution to the crisis, it must be between Nicaragua and the United States” since the government views the detainees as US agents. Like the FSLN revolutionary regime during the early 1980s, Ortega and Murillo cannot acknowledge legitimate domestic discontent; rather, everything must be an imperialist plot.

From this internationally-oriented perspective, Ortega and Murillo are engaging in hostage-taking as a diplomatic strategy. It is difficult to see it working.

First, despite the allegations, the detainees are not US agents. Second, the US has less at stake in Nicaragua than elsewhere in Central America, where migration remains the US focus. Nicaraguan migration to the US has increased since April 2018, but remains low compared to northbound migration from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras.

Third, the new Biden administration is trying (if inconsistently) to reemphasize human rights and democracy, so why would it reward hostage-taking? Instead, the US has expanded sanctions to Ortega and Murillo’s daughter Camila and to additional government officials. US legislators are working to tighten targeted sanctions and to investigate government and Ortega-Murillo family corruption. There is even discussion of suspending Nicaragua’s participation in the Dominican Republic-Central America Free Trade Agreement, though this or generalized sanctions could have deep negative economic consequences and hurt, not help, Nicaragua’s people.

Other international reactions and future scenarios

International institutions have matched the US stance. Costa Rica led 59 countries from the UN Human Rights Council in demanding an end to repression and respect for human rights, echoing UN Secretary General António Guterres’s position. The Organization of American States voted overwhelmingly to “unequivocally condemn the arrest, harassment, and arbitrary restrictions placed on presidential candidates, political parties, and independent media,” calling for “the immediate release of presidential candidates and all political prisoners.” The European Parliament is considering suspending cooperation agreements.

International civil society groups have widely condemned the repression, with organizations like Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch quick to speak out. Over 750 academics and researchers (including myself) signed a statement calling for the Ortega-Murillo government to release political prisoners, end restrictions on civil liberties, and hold free and fair elections; the Central American members of the Consejo Latinoamericano de Ciencias Sociales issued their own declaration. Central American business associations condemned the arrests and threats to regional stability.

Some of Central America’s international institutions, however, have been conspicuously silent, most notably the Sistema de la Integración Centroamericana. Dante Mossi, president of the Banco Centroamericano de Integración Económica, talked past the Nicaraguan crisis, tweeting that the bank “does not condition its assistance on assessments other than economic ones.” The governments of El Salvador and Honduras have kept quiet, too, amid their own deepening authoritarianism and corruption.

Argentina and Mexico’s governments tried to maintain the potential to be mediators, condemning the mounting arrests in Nicaragua and then abstaining from the OAS resolution vote, but they recalled their ambassadors to Nicaragua for consultation amid outcry over the abstentions. Yet what would international negotiations actually entail? If the Nicaraguan government wants sanctions lifted, then relaxing domestic restrictions and moving towards free elections would have been credible positive signals, versus the current crackdown.

Either Ortega and Murillo are deeply misguided about what will shift international actors’ stances, or the call for negotiations is a smokescreen, and the domestic audience has always been their focus. After all, what better way to ‘prove’ again to supporters that they are defending Nicaragua from imperialist intervention than by provoking an international outcry?

The problem with this strategy is that it confirms the biases of the approximately 20% of the population who still support the government without winning new support. The opposition may be more fearful, but it is also more deeply convinced that the government cannot be trusted in any negotiations. The opposition learned this before in 2018, when Ortega and Murillo abandoned the negotiating table to violently ‘cleanse’ the streets of protesters.

Debates about participating in the electoral process are likely to continue, but opposition planning must now be about what happens after November, since Ortega and Murillo are not giving up power. Any future plans for protest and civil disobedience need broad support and clear, domestically-focused objectives. Global attention is now on Nicaragua, but it is fleeting. While international actors can and should play a limited supporting role, solutions to the crisis and positive visions for a more democratic future must come from Nicaraguans themselves.