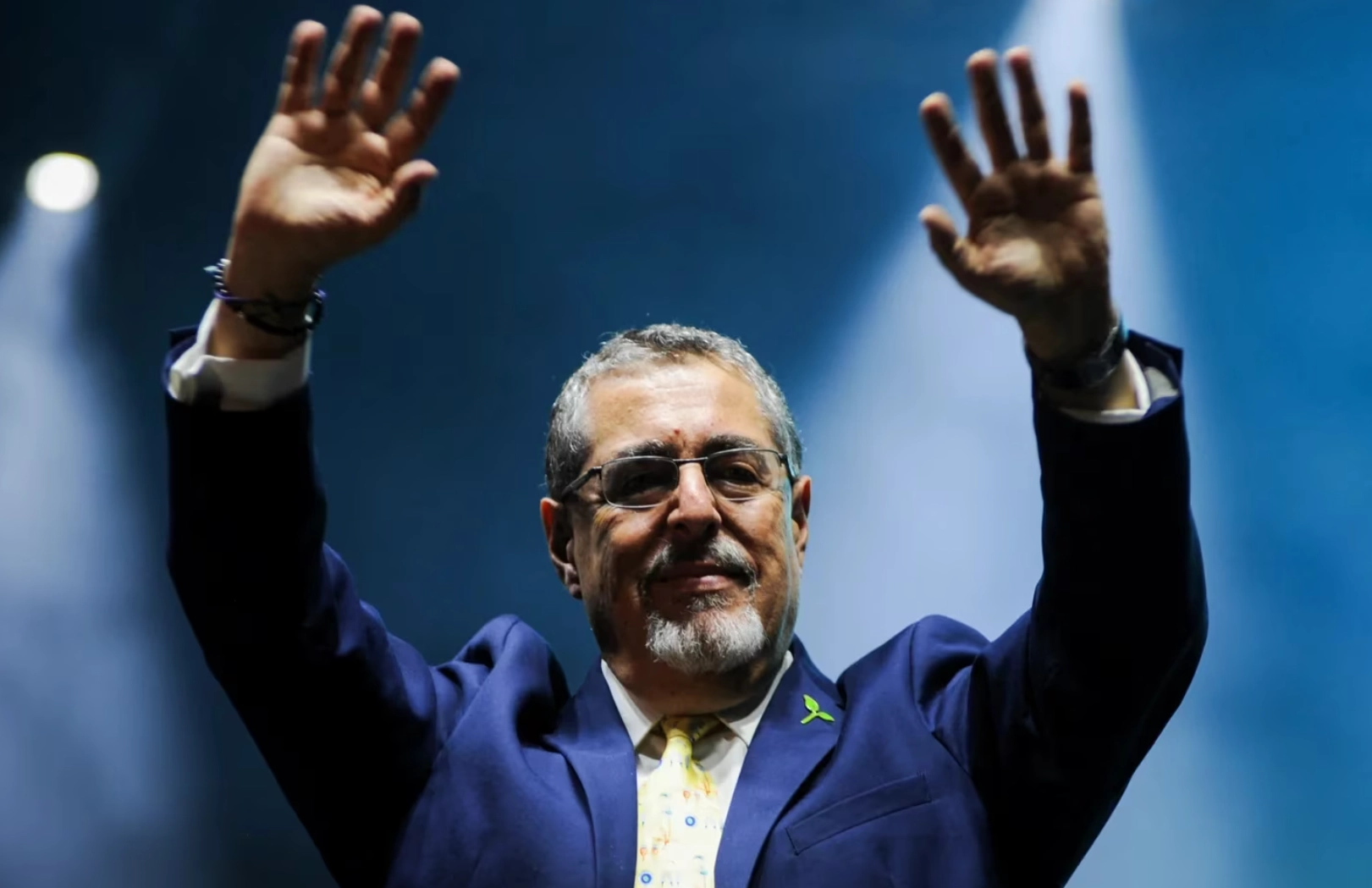

Bernardo Arévalo from the Semilla Movement secured victory with 58% of the votes in Guatemala’s presidential elections held on August 20. However, this isn’t just a defeat for his electoral adversary Sandra Torres from the National Unity of Hope Party (UNE), but also for the system that had held power in the Central American country for decades.

An apparently anecdotal incident sheds light on the tectonic shift underlying this outcome. Arévalo, who lacked significant campaign contributions, received a $100,000 donation from a young entrepreneur and technology advocate, Luis von Ahn. Luis von Ahn is the Guatemalan founder of the language learning app Duolingo. In contrast, during the runoff, Torres received support from, among others, the Foundation Against Terrorism, whose ideological framework remains rooted in the internal conflict (1962-1996) and the “threat of communism.”

Arévalo successfully connected the present (new generations) with the future (technology) of the country. In contrast, Torres embodied the vestiges of a past built on clientelism and patrimonialism, with little legitimacy among both new and old generations.

Bernardo Arévalo’s victory holds historical significance as a vindication of the legacy of Juan José Arévalo—father of the president-elect—who governed from 1945 to 1951. Juan José Arévalo is considered one of the country’s best presidents in the Guatemalan collective imagination due to his role in creating the social security system. His term was cut short by a coup d’état in 1963. The Arévalo name, laden with meaning and connotations, has influenced this victory. In the eyes of the weak Guatemalan collective identity, it’s associated with an era of social reforms and integrity. Bernardo Arévalo’s main electoral banner has been the fight against corruption.

Furthermore, since 2015, Guatemala’s perpetually frustrated society has been seeking a leadership capable of channeling its desires for change, transformation, greater democratization, and transparency. Mobilizations against the government of Otto Pérez Molina (2012-2015) removed a corrupt administration, but failed to generate an alternative leadership or a model change, as anticipated in the outsider Jimmy Morales’ presidency (2016-2020).

Following the disappointment with this comedian-turned-politician, the clientelist system blocked change by obstructing Thelma Aldana’s candidacy in 2019, who was presented under the Semilla umbrella, an organization born from the events of 2015. This allowed Alejandro Giammattei (2020-24) to assume the presidency. He formed a broad informal alliance of parties and interests to co-opt the system, preserving the hegemonic model.

Now, in 2023, a young electorate connected through social media sought to dismantle this system by supporting anti-elite figures: first Roberto Arzú, then Carlos Pineda. The system known as the “pact of the corrupt”, excluded prominent individuals from the electoral race who posed a risk to its survival. Yet, the emergence of Bernardo Arévalo, polling at barely 3% before the first round and proceeding to the runoff with just over 11% due to widespread fragmentation, went unnoticed.

After prevailing decisively in the runoff, Arévalo, with center-left stances, embodies radical change from a moderate standpoint. He ushers in a reformist project that doesn’t seek vengeance. He has assured that there will be no tax increase (instead focusing on improving revenue collection by combating corruption and smuggling), and no alignment with China, but rather good relations with both Beijing and Taiwan within an independent foreign policy.

Furthermore, he presents himself as a reformist (linking his leftist position to the model of Uruguay’s José Mujica), respectful of “all types of private property,” supportive of abortion, but only for therapeutic purposes, and aims to improve health access by strengthening Social Security and breaking the pharmaceutical monopoly through stimulating competition among private entities.

Arévalo has allayed concerns about his leftist origins (center-left, to be precise) by emphasizing that his government won’t initiate land expropriations, increase or create taxes, implement a radical gender agenda, or attack the business sector and armed forces, with which he has built bridges.

Arévalo’s transversal proposal, while moderate, clearly challenges vested interests through his campaign against privilege and corruption. Above all, he aims to sever “the oil that lubricates corruption—the state’s budget for public works—around which the corrupt wills of the Executive, legislators, and corrupt builders revolve.”

Thus, his major challenge will be achieving governability. The institutional framework (parties, Congress, and particularly judicial bodies) has suffered a legitimacy blow due to corporate interests. The new leader arrives with high expectations but limited room for action. Not only does he possess a minority caucus with little capacity to form alliances granting a majority, but also it appears that the bloc of parties more aligned with the system—predominant ones—will attempt to block reformist initiatives.

Moreover, Arévalo, who will face a serious deficit in personnel to complete his administration, is under the shadow of a Damocles sword the system wields to obstruct him: the dissolution of Semilla’s legal status, pushed by the current public prosecutor’s office. This move could result in the disappearance of the parliamentary group, preventing deputies from participating in legislative committees, weakening Arévalo’s support and margin of action.

A complex future undoubtedly unfolds. Nevertheless, one achievement has already been made: Guatemala has voted for the return of a “spring.” Juan José Arévalo governed during the period known as the “democratic spring” between 1944 and 1954. This is something the winning candidate has repeatedly alluded to, hinting at the “autumn of the patriarch (of the system).” Bernardo Arévalo’s challenge is to transform this spring into an eternal one—Guatemala is known as the “land of eternal spring”—and prevent a “winter is coming,” which would be the return of authoritarianism and corruption.

*Translated by Ricardo Aceves from the original in Spanish.