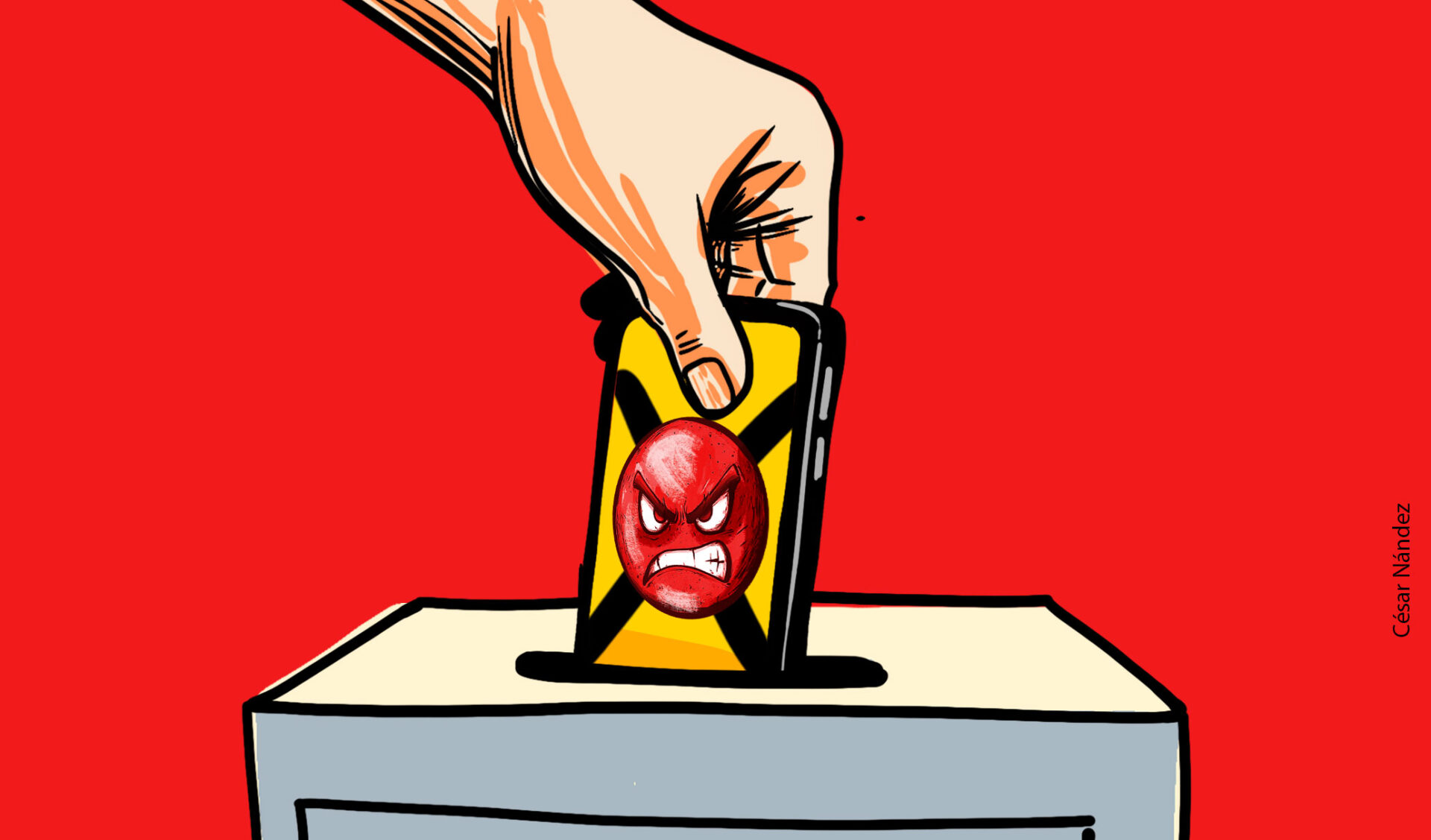

The year 2024 was marked by the large number of electoral contests. More than half of the world’s inhabitants were called upon to participate in some electoral process as many of the countries with the largest populations, such as Brazil, Mexico, the United States, Russia and India, held their elections. This evidenced the deterioration of the integrity of information in the electoral context. The fraud narrative is not a new phenomenon, what is new are the tools used for this purpose.

The actors interested in affecting the elections have a range of options that are now much more accessible, economic and massive, so that the authorities are faced with a sort of hydra with a thousand heads; as legislation to combat disinformation is discussed, new forms emerge that make the issue unmanageable.

Although notable progress has been made in mechanisms to confront disinformation, whether at the level of preventive measures or judicial mechanisms to identify and punish those responsible, these efforts are still insufficient. And beyond the penalties imposed after lengthy judicial processes, the truth is that trust in institutions and actors that have been discredited is unlikely to recover.

The Paraguayan elections of April 2024, for example, were marked by allegations of fraud by a significant sector of the electorate, led by Paraguayo Cubas, (Cruzada Nacional) who obtained 22% of the votes. Through social networks, Cubas claimed that due to the implementation of an electronic voting mechanism (Single Electronic Ballot), fraud had been committed in favor of the ruling Colorado Party. Hundreds of people took to the streets and caused damage to public infrastructure.

In India, almost one billion people were eligible to vote in the parliamentary elections, which began on April 19 and ended on June 1. These elections were marked by the use of sophisticated deepfake technologies, with which, for example, messages from celebrities supporting certain parties or candidates were falsified. Real videos were also manipulated, including those of the Prime Minister, attributing to him false statements for the purpose of damaging his image.

The European Parliament elections, in the context of the Russian aggression against Ukraine, were of particular importance. According to the European Digital Media Observatory, May was the month in which the record amount of disinformation against the European Union was recorded on online platforms. As early as February 2024, the Parliament passed a resolution condemning Russia’s continued efforts to erode democracy. The document notes that the Kremlin recruited some parliamentarians and funded European parties to influence the parliamentary agenda and exacerbate polarization. Finally, the European Parliament demanded the deepening of sanctions on Russian media that spread disinformation (RT and Sputnik).

Another case of disinformation through Russian interference has been registered in the Georgian elections. The ruling party “Georgian Dream”, which has affinity with Putin, promotes a conspiracy theory that the West is controlled by the “party of war”, an elite that controls the institutions and seeks to open a new war front on Georgian territory. The latter, for its part, has been accused of forging Georgian Dream posters with messages of submission to Russia. Atlantic Council reported that Meta had to remove a Russian-driven campaign that criticized the protests of pro-European groups and provided support to “Georgian Dream” through various “news” websites and other platforms.

The US elections, perhaps the most important in the world in terms of relevance and impact, did not disappoint either. The candidate who was elected, Donald Trump, had already made unjustified allegations of electoral fraud in 2020, and subjected the electoral and justice system to an institutional stress never seen before in the country.

The contest would be defined in a few states, among which Pennsylvania had a special importance. It is no coincidence that precisely in Philadelphia, its most populated city, rumors spread about failures in the voting machines. Trump posted on Election Day on his TruthSocial account, “There is a lot of talk about massive TRAPS in Philadelphia. Law enforcement is on the way.” After the polls closed and results were released in the swing states confirming the Republican victory these rumors dwindled to almost nothing.

The Washington Post analyzed the behavior of the publications of an X community called “electoral integrity” which was created by Elon Musk, a fervent promoter of Trump’s candidacy. The analysis shows that as Trump’s victory was confirmed, allegations of electoral fraud decreased.

Although this time the situation did not reach the gravity of the previous election, the judicial processes against media outlets that defamed some companies that developed electoral technology in 2020 continued to advance.

Last year, and after the unfounded allegations by the Trump team in 2020 that they had suffered a massive fraud through the manipulation of voting machines, it was known that Fox News reached an agreement with the company Voting Dominion System for US $800 million to avoid going to trial for defamation.

In the case of the United States, some of the actors who have spread electoral disinformation have been brought to justice and have been forced to reach agreements with the victims of their hoaxes and publicly accept their wrongdoing.

Finally, we close 2024 with the case of Romania. Just as in Georgia, Russian interference was denounced, in this case by circumventing electoral campaign controls through the use of TikTok. Candidate Georgescu, who in the polls was not among the favorites, ended up winning the November 24 election. Openly pro-Russian and presenting himself as a guarantor of peace (for not confronting Putin’s pretensions), he assured that he did not have the funds to campaign. However, after the surprising result the Romanian authorities detected an articulated support to his campaign from more than 25 thousand TikTok accounts whose publications were coordinated through a Telegram channel that indicated how to evade the content verification system.

In a controversial decision, the Supreme Court annulled the results of these elections and an investigation was launched into Georgescu’s closest circle, which would end in arrests of people linked to organized crime. Some of the influencers who supported his candidacy fled the country, and the pro-Russian links of some of them could be proved.

It is clear that the scenario is not encouraging. The tools to attack the integrity of information in the electoral context are increasingly accessible, inexpensive, harmful and often leave no traces, which makes it difficult to identify and punish those responsible.

Although for years different academic and governmental institutions, think tanks and specialists have been working to design measures to combat disinformation, the mechanisms to influence elections are increasingly sophisticated and rely on a natural predisposition of people to confirm their convictions (confirmation bias), regardless of how true they are.

*Machine translation proofread by Janaína da Silva.