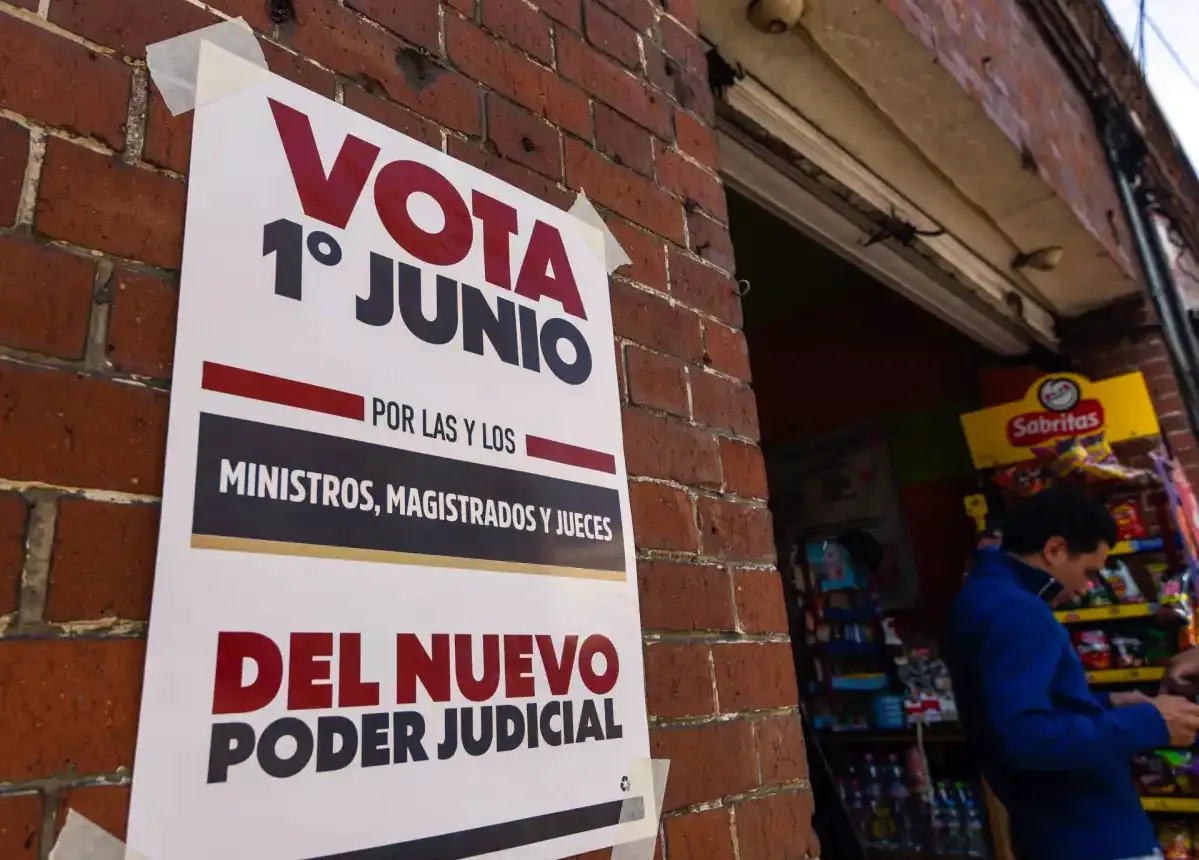

On June 1, Mexico will hold “unprecedented” elections: members of the judiciary will be elected, and each voter will receive at least six ballots. Depending on the state and the offices up for election, a voter could receive up to twelve ballots and cast at least 31 votes. To illustrate, for the selection of members of the Supreme Court of Justice (SCJN), each voter will choose 9 individuals from among 64 candidates on a single ballot. More than 99 million people are eligible to vote. Based solely on the SCJN election, there are hypothetically more than 27 billion possible result combinations. Due to its irrational origin, its rushed and unexamined implementation, and other aggravating factors, this election may mark the end of democracy in Mexico—or at least its most severe weakening, which will be difficult to recover from in the short term. Despite all this, there is no popular rejection of these elections, and they are not even perceived as concerning. What will be the effects on the administration of justice? How will it impact the balance of power? And above all, to what extent will it damage or not damage democracy?

The creation of trust in elections in Latin America was a very complicated and complex process. The democratic transitions at the end of the 20th century initially aimed to remove authoritarian elites from power—in many cases, the military, as in Argentina, Brazil, and Chile; in others, political parties, as in Mexico. But once that goal was achieved, it immediately became necessary to establish the political and legal foundations to legitimize the new democratic governments.

Elections obviously legitimize governments, but behind them lie technical procedures without which no election can be considered democratic. That is why many of the new democracies created electoral bodies with broad formal powers, endowed with political autonomy and technical independence, to protect the management of elections. As Ortega y Gasset noted in 1933, the health of democracies depends on the electoral process, that “miserable technical detail.” This is how the Electoral Tribunal in Brazil was created in 1988, the CNE in Bolivia, the IFE in Mexico in 1989, the TSJE in Paraguay in 1992, and other electoral bodies throughout the region. In other cases, existing institutions were reformed and given new powers, but especially independence, to ensure impartial technical performance.

Over 40 years since the region’s democratic transitions, electoral bodies have functioned “well” in most countries. In others, however, they have been co-opted and subjected to reforms that distort their objectives—as occurred with the CNE in Venezuela and the now Plurinational Electoral Body in Bolivia. In the latter case, in addition to organizing regular executive and legislative elections, under Evo Morales’ regime it was tasked with referendums, recalls, and eventually, as in Mexico, judicial elections beginning in 2011.

Bolivia’s experience has shown that subjecting those responsible for administering justice to elections undermines the integrity of the electoral process and distorts democratic design. Although it is true that until a few decades ago judges and magistrates were elected in various parts of the world, this was done to differentiate them from appointments once made by monarchs and their ministers. But as these functions became more complex and technical, and democracies became more robust, judicial appointments were replaced by merit-based career systems—with few and tightly controlled exceptions—to shield them from undue political interference.

In Mexico, trust in electoral processes has always been a sensitive issue—at least during the last two decades of the 20th century and the first of the 21st. Faced with a deeply distrustful society, the “solution” was an electoral management system differentiated in its functions and territorial reach. Two federal bodies were created: an electoral justice tribunal, the (now) TEPJF; and an electoral management body, the (now) INE. At the same time, a subnational system was consolidated, with 32 local electoral bodies likewise divided between justice and management. This system also reflected Mexican federalism and enabled the most important elections of the democratic transition: those of 1997 and 2000. It adapted to challenges from subsequent elections and functioned this way until the 2012 presidential election.

The 2013 and 2014 reforms created a hybrid system that duplicated functions and costs, generally complicating electoral management and justice. Although it adapted over time, it essentially dismantled electoral federalism. Today, electoral management and justice are centralized due to the powers granted to national institutions, reducing local institutions to mere executors of national directives.

This framework enabled the unprecedented 2021 “popular consultation” to try former presidents, in which only 7.11% of citizens participated. It also enabled the 2022 recall process, which was in reality a plebiscite to measure the president’s popularity and Morena’s mobilization capacity, with only 17.77% voter turnout.

Judicial elections will also be “unprecedented,” and electoral participation is likely to be very low. But the deeper problem is that trust in elections is already compromised. The integrity of electoral management is eroding due to the questionable performance of both the TEPJF and the INE Council, which no longer penalize the ruling party’s illegal interference in the elections.

Mexico’s electoral institutions are co-opted, subdued, and overloaded with new tasks—tasked with organizing electoral processes that, in effect, damage democracy. Formally, they cannot refuse, even though some members (not all) are aware that these activities strengthen the ruling party and erode democracy.

Their role resembles that of the robot in the 2016 installation Can’t Help Myself by artists Sun Yuan and Peng Yu at the Guggenheim Museum in New York. It was a robotic arm programmed to continuously scrape up a dark liquid leaking from its base—otherwise, it would cease to function. Over time, it began to move more slowly; its mechanical task became increasingly monotonous and rigid, its only objective “survival.”

Today, Mexico’s electoral bodies, which once fostered trust in elections, function in the same way. Of course, they still carry out their duties, but their integrity is damaged—the only question is how much.

*Machine translation proofread by Janaína da Silva.