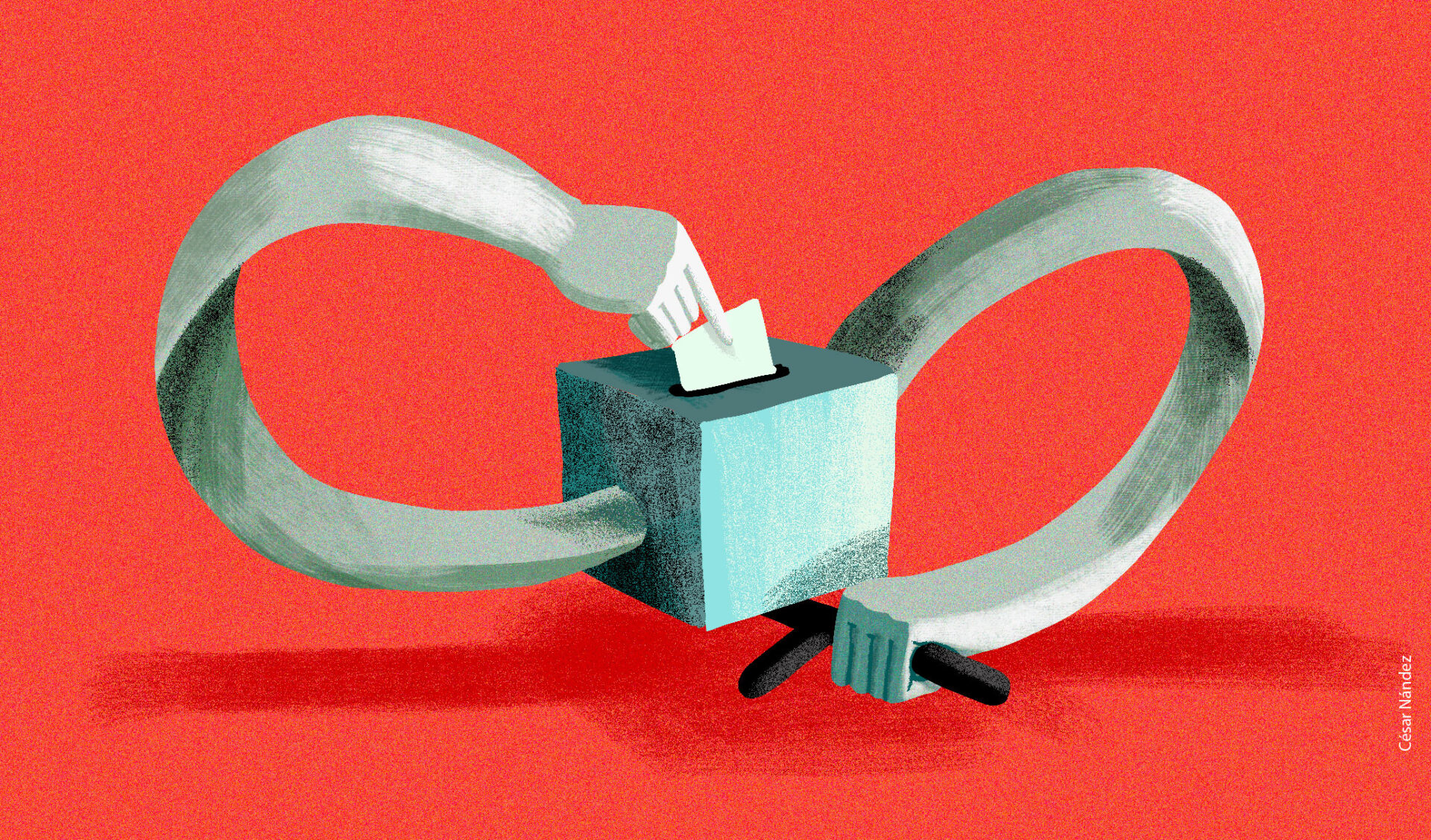

Reelection is a taboo subject for many countries. Some have eliminated it from their legislation and others have it because presidential terms are short. In other cases, it is argued that having no term limits on the presidency allows continuity to be given to a government that has given results.

Nevertheless, in the 21st century, several Latin American countries have seen how presidential reelection has been a door to tarnish democracy and, with it, build autocracies. It should be noted that reelection within the constitutional framework and with a finite term is not dangerous by itself; political scientists such as Aníbal Pérez-Liñán argue that the fact that an executive remains in power for a second term is a way of rewarding him.

The American, Argentinian, and Brazilian presidential models allow immediate reelection for only one term. In this way, a lock is established on presidents to avoid the concentration of power and the entrenchment in office. Political scientists such as Andrew Ellis or Jesús Orozco Henríquez consider that the model of a second continuous term or staggered reelection constitutes a barrier to the accumulation of power.

In cases such as Chile or Uruguay, which prohibit immediate reelection, it is necessary to wait for a legislature to run again for the office of the Executive Power. This model allows for a period of transition and pluralism to prevent an institute or character from consolidating more power.

The seduction for power is a latent desire in politicians from different latitudes. However, constitutional and time limits are a barrier for them, as Adam Przeworski mentions in his book La democracia en crisis. Even so, in the first decades of the 21st century, some presidents have accumulated enough power to pressure the constitutional courts and thereby endorse their reelection by eliminating legal barriers.

In recent times it has been through court rulings that have argued that reelection is a way to reward an administration of results, but lately it has been added to the argument that it is a human right; therefore, to limit it would be to prohibit the rights of political actors.

The literature and the major legal treaties such as the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen (1789) or the Universal Charter of Human Rights (1948) only establish freedom of association for men and women, but do not mention that reelection is part of these guarantees. In fact, classical theorists such as Rousseau, Locke and Bentham mention the importance of limiting political power.

Although the most well-known legal theorists such as Kelsen, Heller, Jellinek or Rawls establish the limits, the respect for the maximum laws and the legal framework of the State. What has been seen in these times is a malleability of the law to favor a character, as has happened with the rulers of Venezuela, Nicaragua, Honduras, Ecuador, Bolivia and recently El Salvador, which joined this list of countries that maintain that reelection is a human right.

The first country to implement it was Venezuela in 2009 during the third mandate of Hugo Chávez, who reformed the Magna Carta under the argument that indefinite reelection is a human right. Upon review of the case by the Supreme Court of Justice, it was mentioned that eliminating the control of temporality did not imply a change of regime or form of the State, but rather a broadening of the rights of the citizenry. The decision opened the door for Chavismo to gain a foothold in power and democracy began to erode.

In the same year, but in Nicaragua, during Daniel Ortega’s first term of office in the 21st century, the Constitutional Chamber of the Supreme Court opened the way for indefinite reelection with the same argument of being a human right. Nonetheless, in contrast to Venezuela, Ortega had already subdued the Judicial Power: thanks to a reform, he increased the number of magistrates of the highest court, who, being close to him, declared the constitutionality of the project.

As a result, Orteguismo has remained in power uninterruptedly since 2006. Counterweights have been eliminated and Nicaragua is moving towards an autocratic model. During the second decade of this century, three more countries would join the indefinite reelection. In 2015 it was neighboring Honduras, when the Constitutional Chamber approved that the then president, Juan Orlando Hernández, could run for another term. Let’s remember that he came to power through a lawfare or soft coup d’état against the leftist president Juan Manuel Zelaya.

Also in 2015 in Ecuador, under the third term of President Rafael Correa, Alianza-País legislators approved a constitutional amendment to introduce indefinite reelection. Despite the fact that the ruling ended up in the Constitutional Court, the latter validated it arguing that it was a decision that expanded the political-electoral rights of the citizenry, since if a president made a good government the voters would reward him. It was in 2018 when the temporality lock was reintroduced in the Constitution.

A year later, in 2016, in Bolivia, the Movimiento Al Socialismo (MAS) party sought to hold a referendum to modify the Magna Carta and include indefinite reelection. Between 2017 and 2018, the Supreme Court of Justice took up Article 23 of the American Charter of Human Rights to endorse it. With this precedent, Evo Morales sought a fourth term in 2019, which resulted in protests that culminated in his resignation and departure from the country.

Finally, in 2021 El Salvador joined this list. On February 5, 2024 the world witnessed the first reelection of Nayib Bukele, despite the fact that the Salvadoran Constitution prohibits immediate reelection in at least 9 articles. The Salvadoran path was similar to the Nicaraguan one. The Nuevas Ideas party promoted a bill in the National Assembly to allow the reelection of the president. After its approval, 5 magistrates of the Supreme Court resigned and Bukele appointed profiles close to him, so the project of immediate reelection was approved arguing that it was a human right. The only thing that was established was that the executive had to leave office 6 months in advance.

As shown, several countries have used the argument of human rights to open the door to indefinite reelection. These cases are mainly characterized by the fact that personalistic and authoritarian leaders govern them; therefore, the checks and balances in the democratic system are captured or eroded.

*Translated by Micaela Machado Rodrigues from the original in Spanish.