Currently, the powerful multinational companies that produce Ultra-Processed Foods (UPFs) have found a completely fertile field to continue advertising their products on digital-social networks, even outside the laws in countries where there is legislation, such as Mexico. Recently, the Mexican consumer protection organization Tec-Check A.C. has shown that the main producers of UPFs operate freely on the web, in the absence of a clear legal framework for their digital advertising.

UNICEF, the World Bank, and the World Health Organization (WHO) estimate that one out of every three children and adolescents between 5 and 19 years in the Americas, the region with the highest incidence among those covered by this organization, is overweight or obese. Considering adults, the problem is more serious: it reaches 62.5% of them.

These products identified by WHO and PAHO as the main causes of the global pandemic of overweight and obesity or “globesity”, have strong restrictions in traditional media. These products cannot be advertised to minors, cannot use mascots or personalities on their packaging, must contain warning labels for excesses of harmful ingredients such as fat, caffeine, sweeteners, sugar, and sodium, and cannot be recommended or used by children or adolescents in their communication, among other restrictions.

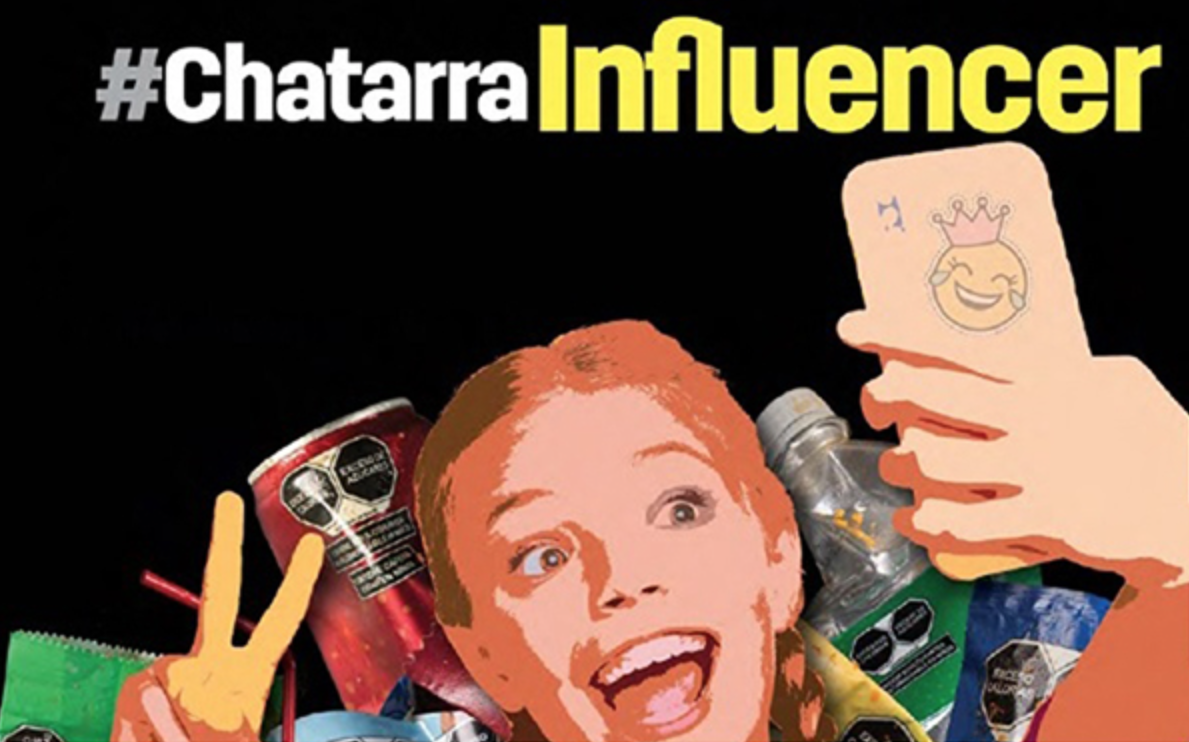

However, in their digital advertising on networks such as YouTube, Instagram, or TikTok there seems to be a legal loophole since none of those restrictions are observed in their commercial communication openly aimed at children and teenagers. In addition, the figure of the “influencer” has emerged as the most credible, especially among their peers. In fact, due to their anthropological characteristics, they tend to be perceived as one more, among the most unprotected audiences; children and teenagers.

This figure has proven to be very efficient for UPF brands but especially dangerous for children and adolescents. With integrated product strategies that can hardly be identified as advertising, peer influencers of children and adolescents openly use and recommend sugary drinks, and sweet and salty snacks with sales arguments that would have no place in any traditional media without being subject to a powerful sanction.

In addition, in an environment of the attention economy, as Yves Citton has called it, UPF brands compete for attention with increasingly attractive proposals distributed across a multiplicity of screens. This is where the junk influencer or influencer of junk food has its ideal environment.

Peer influencers have a special charm among audiences, as they do not present themselves as an authority, tutor, or preceptor, but as a trusted figure who has the same characteristics (in appearance) as the user who receives their messages. For example, the Ultra-Processed Cereal (UPC) campaign for the most recognized chocolate-flavored puffed rice in Mexico was developed through a popular teenage influencer on TikTok. She composed a song dedicated to this product, resulting in more than 5.5 million interactions and shared by at least a dozen peer influencers.

This is how children and teenagers get hooked and get involved in increasingly commercial content in a context of content and narrative where UPFs are not stars, but reliable companions recommended by very attractive characters who act as role models and peers.

To deceitfully motivate children and teenagers to satisfy adult needs is, by definition, predatory.

What is the responsibility of political decision-makers, who despite the existence of legislation do not put it into practice? When will the organizations producing UPFs put the health of their consumers before their profits? What role do the adults and guardians of these minors play in minimizing or ignoring front labeling?

All this is happening in Mexico, despite being a country that has laws that have served as an example for other countries, such as NOM-051 on front labeling for food and beverages, the prohibition in the State of Oaxaca to selling UPFs to minors or the restrictions on advertising of these products in media at times considered to be for children.

Now we only need to apply these laws to digital platforms. It is not a minor issue.

*Translated from Spanish by Janaína Ruviaro da Silva