X (former Twitter) is useful to make friends and enemies without even knowing them. It serves to assemble and disassemble affinity groups. To communicate and to insult. To inform and to entertain. To solve problems and to waste time. To unite us and to divide us.

Leaders and influential people use this platform to spread their phrases, convey their impressions, and communicate with their audiences and followers. Presidents use it to announce their decisions. What has not happened so far is that two countries have seen their relations deteriorate and put their governments on the verge of rupture due to an escalation of insults and verbal aggressions between presidents that are channeled through X, going beyond their usual diplomatic relations.

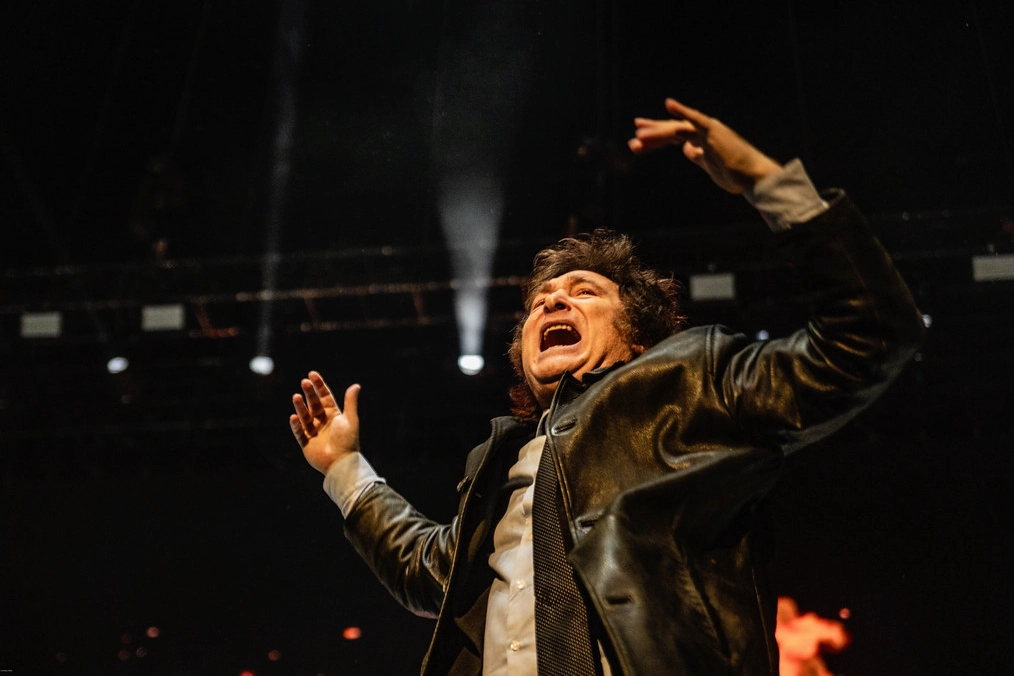

This is what is happening with the saga of insults and outbursts that Argentine President Javier Milei has been lavishing on each other, describing Mexican President Andrés López Obrador as “ignorant” and Colombian President Gustavo Petro as a “terrorist and communist murderer”. The latter, on his part, had already referred to the Argentinean president with harsh adjectives in a fight that have been going on for several months.

The ideological enmity moves to the level of personal enmity, and a president ceases to represent his country before the world to become the representative of those who voted for him and sympathize with his ideas, at home and abroad.

Thus, relations between states disappear to become a combat arena or virtual Roman circus in which gladiators fight their battles as a representation of a war between nations, while the digital audience — massive multinational fans — acclaim some and revile the others by posting, commenting, and reposted their barbarities. The expletives that are uttered attract attention, generate trends, and have a real impact that forces the chancelleries to activate their crisis protocols, while one and the other blame each other for who started it.

Xóchitl Gálvez, a presidential candidate of the Mexican opposition, put it in its proper terms when commenting on the last crosses: “We wash the dirty laundry at home”, she wrote in her X account, “I do not allow Javier Milei to speak ill of Andrés Manuel López Obrador. I’ll take care of that one.” Meanwhile, Milei, far from apologizing to his Colombian counterpart, reposted messages in his support such as this one: “The former guerrilla and narcomarxist @petrogustavo did us a favor: one less Embassy to maintain in a country that, as long as it is governed by this criminal, becomes unviable”.

Indeed, it is not the fault of social networks that politicians are behaving like hotheads or troublemakers, a novelty that we owe to Donald Trump and in which presidents like Nicolás Maduro or Daniel Ortega move like fish in water. Although the characteristics of social networks are reformatting the heads of those who surf for hours and hours reading, writing, and posting short messages, light judgments, vulgar comments, and unverified data.

They are new ways of communicating and participating, say the gurus of their favorable impact, which streamline and make horizontal public life, eliminating intermediaries in the great global Agora. Now we are entering a new dimension: diplomatic conflicts can be settled, processed, or generated through social networks and even break relations through X.

In the case of a figure of Javier Milei’s eccentric characteristics, it is difficult to know why he does it, whether to win friends or enemies, whether to communicate or to insult; whether he is acting seriously in this way in response to his ideology or whether he is simply having fun and seeking to entertain the audiences that follow him. Whether to show himself as an “enfant terrible”, a born provocateur or because he believes it is the best way to convey his libertarian ideas.

After all, as Argentine Foreign Minister Diana Mondino pointed out, “Presidents are one issue, and relations between their countries are another”. Thus, presidents can give free rein to whatever they feel like saying and can behave like arsonists while their foreign ministries run after them like firemen to put out the fires they start, without damaging bilateral relations. For a culture as strongly presidentialism as Latin America’s, it sounds like a somewhat naive or puerile argument.

*The original version of this text was published in Clarín.