Latin America is experiencing a decisive fiscal moment. After the pandemic, governments face stagnant tax revenues, persistent inflation in several countries, debt servicing that consumes a large share of national budgets, and an exhausted citizenry that watches with growing distrust the State’s ability to provide basic services. In this context, the notion of a so-called new fiscal pact has begun to occupy the center of public debate, but in reality it conceals a dilemma that has dominated regional discussions for decades: should the region move toward greater tax progressivity or toward spending adjustment?

The way this question is framed is decisive. Recent history shows that reforms focused exclusively on raising taxes on higher-income sectors, as well as those based solely on cutting public spending, have failed to stabilize fiscal accounts or generate sustained growth. Neither path, taken in isolation, offers a lasting solution. The real debate—much more complex, but also more honest—lies in defining what kind of State is to be financed, what tax structure can sustain it, and how to ensure that public resources are managed with transparency, efficiency, and legitimacy.

To understand the scale of the problem, it is useful to look at some official figures. According to OECD data, average tax revenue in member countries is around 34% of GDP. By contrast, in Latin America, according to ECLAC, tax revenues amount to roughly 21% of GDP. The gap is evident, as the region attempts to finance welfare-state expectations with a fiscal structure typical of economies that collect far less. At the same time, the pandemic left behind higher levels of debt. ECLAC itself estimates that regional gross public debt stands at around 50% of GDP, with several countries above 70%. Although these figures are far from those observed in developed countries, the difference lies in the cost of credit: while they can access cheap financing, Latin America must do so in riskier markets and at much higher rates. As a result, debt service represents, in many cases, the largest spending item within national budgets.

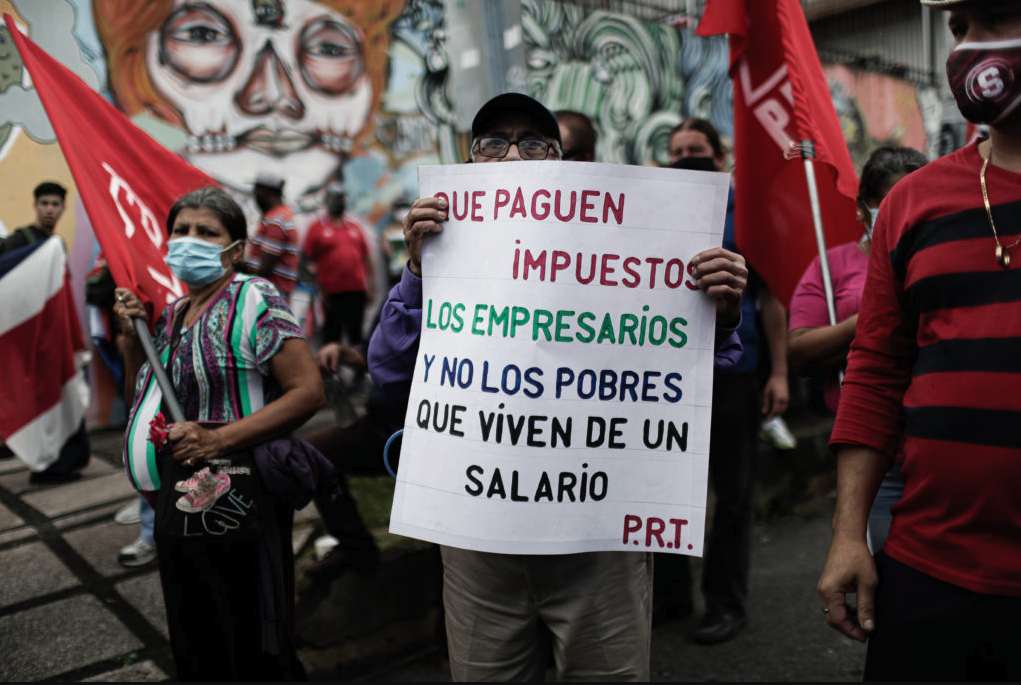

The outcome is a narrow fiscal margin, pressured from two fronts: an insufficient tax structure and a financial cost that continues to rise. This situation fuels the idea that there is no choice but to adjust, yet adjustment has already been a recurring practice in the region without generating a path of lasting stability. Permanent austerity yields diminishing returns, because after successive cuts, what remains to be adjusted is usually infrastructure, science and technology, education, or health policies—precisely the sectors with the greatest potential to drive future economic growth. Moreover, experience shows that cuts tend to fall disproportionately on those who depend most on public services, exacerbating social tensions and weakening government legitimacy.

On the other hand, tax progressivity on its own does not offer a complete solution. While it is evident that the region needs more equitable systems—Latin America remains one of the most unequal regions on the planet—institutional realities limit the scope of such reforms. According to ECLAC, tax evasion and avoidance account for between 6.3% and 6.7% of regional GDP, a figure that far exceeds the average of comparable economies. This level of noncompliance undermines any attempt to build a fairer system, because potential revenues fail to materialize and because it feeds the perception that the fiscal effort is not distributed equitably. Added to this are so-called tax expenditures, embedded in special regimes, deductions, and exemptions that amount to significant shares of GDP and often benefit sectors with strong political influence. Reducing or eliminating these benefits could generate more resources than several combined tax reforms, without directly affecting the most vulnerable groups.

The challenge, then, is not to choose between progressivity or adjustment, but to understand why the region has failed to articulate a balanced and sustainable fiscal strategy. Part of the problem is political, since fiscal pacts require broad and lasting social agreements. In a region marked by polarization, party fragmentation, and low interpersonal trust, building consensus is extremely difficult. Citizens distrust the State because they perceive corruption, inefficiency, and inequality in the use of resources. And governments distrust citizens because they face resistance to any attempt at reform, whether revenue-raising or aimed at rationalizing spending.

Despite this tension, a new fiscal pact is not only necessary but inevitable. For it to be viable, however, it must be based on some minimum principles, such as expanding the tax base before raising rates. Economic informality—which in several countries exceeds 50% of the labor force—prevents a significant share of the population from contributing to state financing. Reducing informality through simplified regimes, real incentives for formalization, and process digitalization could generate more sustainable revenues than successive tax reforms. Tax exemptions and benefits must also be thoroughly reviewed. These mechanisms, often introduced as temporary stimuli, end up becoming permanent privileges sustained more by pressure than by evidence of results. Tax administration must likewise be strengthened and evasion gaps closed. To achieve a significant reduction in noncompliance, countries need to invest in technological capabilities, database interoperability, regional cooperation against illicit financial flows, and the professionalization of revenue-collecting institutions. Even modest reductions in evasion could generate resources equivalent to several points of GDP, surpassing the revenue impact of many tax increases.

Complementarily, it must be ensured that public spending is directed toward goods and services with high social returns. This is not about avoiding all adjustment, but about applying it selectively—eliminating duplications, modernizing administrative structures, and combating the capture of public resources by privileged groups. The key is to protect investment in education, health, infrastructure, citizen security, and the energy transition—areas where economic and social benefits are greatest and most enduring. Finally, a credible fiscal pact must link revenues to results. Citizens are more willing to accept additional contributions when they perceive that the state uses resources transparently and efficiently. Mechanisms such as earmarked budgets, periodic impact reports, or visible audits can strengthen the legitimacy of reforms and reduce social resistance.

In Latin America, where trust in institutions is low, this agreement will not be easy. It will require economic elites to give up privileges, governments to demonstrate a real commitment to efficiency and transparency, and citizens to understand that without a stronger fiscal base it is impossible to sustain a state capable of providing security, well-being, and development. Leaving behind the false dichotomy between progressivity and adjustment means recognizing that both elements are part of the same social contract. Progressivity is necessary to build a fair system, but it requires a credible state. Adjustment is inevitable at certain moments, but it must be intelligent, selective, and aimed at improving the quality of spending—not at weakening essential services. The real task is not to choose between one or the other, but to articulate a strategy that coherently combines both dimensions. The region does not simply need more taxes or less spending. It needs a different state—more efficient, more transparent, more capable, and more legitimate. That is the pending fiscal pact; everything else is merely accounting that, without deep reforms, only postpones the next crisis.