In Argentina’s presidential elections, there is a confrontation between classic populism and the new populism of the far right, whose most famous icons are former presidents Donald Trump and Jair Bolsonaro. The question is whether Argentines (or at least most of them), often criticized for not looking beyond their own problems and virtues, can learn from the global lessons of the new populism and the misery and hatred it engenders. A Milei triumph represents hope for the enemies of democracy.

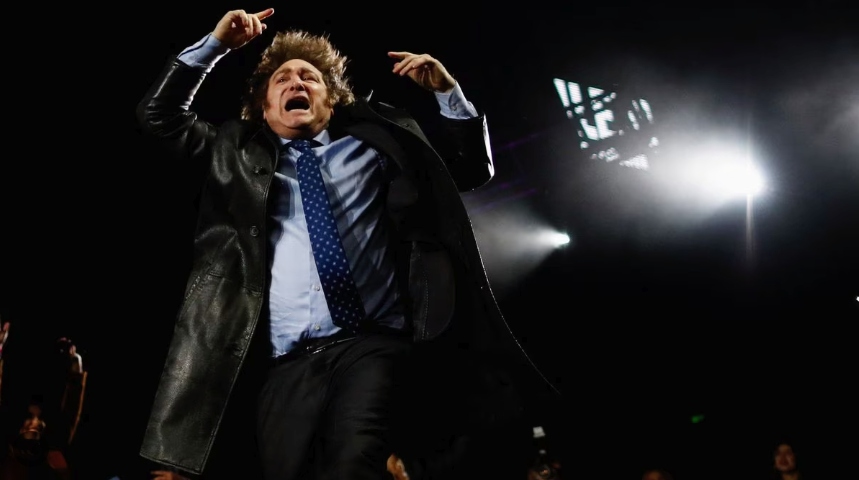

Like so many representatives of the new far-right populism, Milei is characterized by his vulgarity, his intolerance, his attacks on the press, and on the values and rights of democracy. He presents a true cult of the leader that denies science, takes advice from a dead dog, and revolves around his narcissism and emotional instability. It must be understood that Milei is not liberal, center-right, or libertarian as he wants to present himself, but rather a far right-wing populist with a fascist vocation.

Although he is not a serious character in many ways, he cannot be underestimated, since he presents a anti-democratic ideology. The fact is that, like Trump and Bolsonaro (or Víktor Orbán in Hungary, Vox in Spain, or Giorgia Meloni in Italy), politicians like him are against pluralism in democracy. To a greater or lesser extent, they are messianic leaders, violent and erratic individuals who promise magical solutions and symbolic or practical violence.

Milei is a demagogue who uses props like hammers to display fantasies about a state without state, a state without institutions. He promises violence against state institutions and perhaps against those he does not like. Milei’s campaign symbol is a chainsaw and in 2020 he announced his entry into politics by promising violence against his enemies: “I’m going to get into the system to kick them out on their asses”.

Fascism is formulated based on a modern idea of popular sovereignty, but in which political representation is eliminated and power is fully delegated to the dictator, who acts on behalf of the people. The new populists, enlightened by their fascination with themselves, also understand power as delegation and even return to the violence, lies, and hatred more typical of fascism than of classical populism.

In the country where populism first came to power in 1946 with General Juan Domingo Perón, Sergio Massa, the candidate of Peronism and current minister of an economy in crisis and a failed government, presents himself as the moderate option as the candidate of a cordon sanitaire against the anti-democracy of the mini-Trump Milei. Massa has to convince many anti-Peronists and anti-Kirchnerists that voting for him does not mean supporting him or his party, but voting against the anti-democratic option that would endanger the country’s institutions. At the same time, he has to convince Peronists and Kirchnerists that he also represents them. And perhaps also convince many potential anti-Peronist voters of Milei not to vote for the extremist and vote blank.

The challenge for Massa is to convince Argentines who did not vote for him in the first round that he represents a lesser evil since the remedy embodied by Milei is worse than the disease. It is not much, yet it is not little either. As the great Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges said in a poem, “We are not united by love but by fear”.

The question is: What will those who did not vote for Massa or Milei in the first round do? Will they vote to punish a classic populist government whose flaws and problems are evident or to defend democracy and its institutions? On a rational level: no one who believes in the value of democracy should vote today for an anti-democratic candidate. However, unfortunately, this election is not so much about reason but about Milei’s lies, propaganda, and demagogy.

In Argentina, Milei is often discussed as if he had a rational logic. It is a mistake to think that such an extreme and unstable populist, who makes hatred the axis of his “program”, could go into moderation in the second round, as he did when he affirmed that there would be room for the left in his cabinet. This call responds to his desperation to attract votes at any cost.

To the right, Milei has allied himself with former President Mauricio Macri and his failed candidate Patricia Bullrich, whom in the past he called fascists. And as if that were not enough, he recently labeled his new ally as a murderer and terrorist. His alliance with unionists of the old regime and his praise to those who yesterday represented the old system, confirm that at this point Milei will say anything to gather votes.

Milei’s most significant support is among those under thirty years old. Many of them raised the need for a generational change and branded the center-right voters as “old piss-takers”. But now they need their votes. In fact, some had already announced that they would support him in the second round before their party was defeated. Among them, former President Macri represents the center-right sector that wants to play Von Papen, that is, the conservatives who in the Weimar Republic supported fascist extremism.

Let us remember that Milei is the macho-populist and anti-science candidate who believes he is a “professor” of tantric sex and who assured that he could “stay three months without ejaculating”, who considers it necessary to enable the free sale of organs and deregulate the sale of arms or who assures that climate change is a communist invent. Milei is still the same as always, and he will not stop being so. His change is a break with the known and the approach to the abyss. Something unknown locally but already experienced by Brazil and the United States: paraphrasing Max Weber, is the politics of irresponsibility.

Will Argentina be left in the hands of people incapable of governing? Those who see behind his shouts an unstable and vulgar personality will vote against the mini-Trump candidate Milei, while others will abstain. But unfortunately, many buy the anti-political message without seeing what is behind it: a risk to our democracy.

*Translated by Janaína Ruviaro da Silva from the original in Spanish.