It took just over ten years for the World Wide Web, invented by Tim Berners-Lee in 1989 and opened to the world in 1991, to reach a third of the planet’s population and almost 2.5 billion interconnected users in 2012. On January 18 of that year, however, the Internet stopped working.

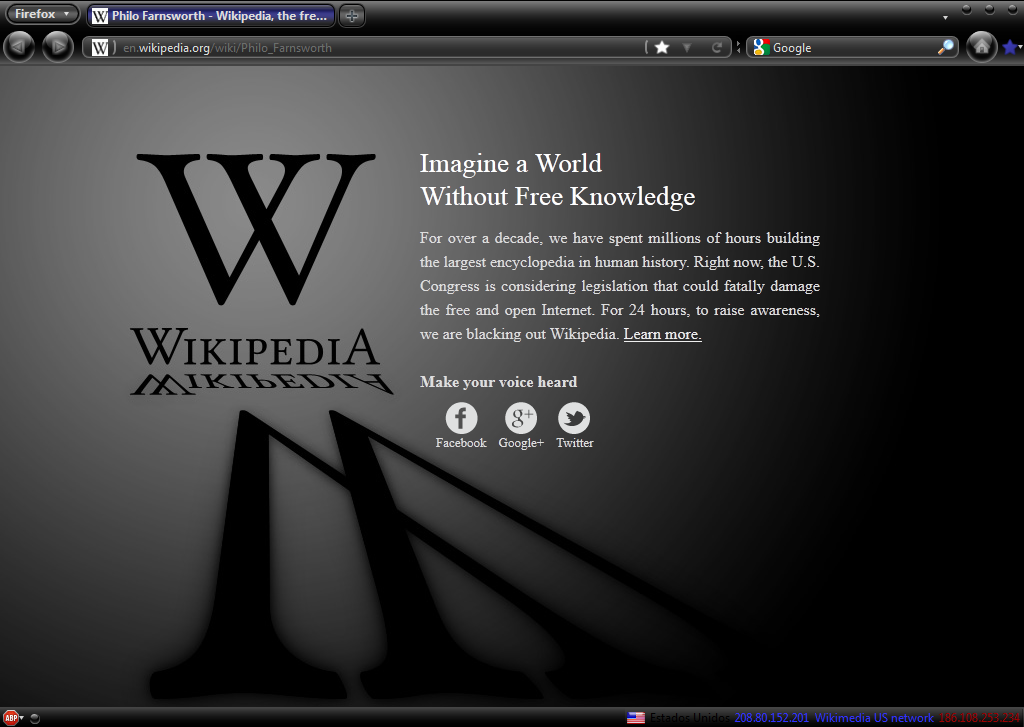

The global network outage was not due to any technical problem; it was, in fact, a political act, prompted by thousands of digital platforms temporarily deleting or interrupting their online content to protest against two bills being considered by the U.S. Congress. Those who tried to visit some of the most popular websites at the time on January 18 were met with messages opposing the Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA) and the Protect Intellectual Property Act (PIPA).

These legislative proposals represented the U.S. cultural industry’s silver bullet against what they called “digital piracy,” a category that included unpaid access to cultural goods on the Internet, even if for one’s own consumption. Backed with an iron fist by the film and phonographic industry associations, these bills, if passed, would expand the enforceability of U.S. copyright law to include downloading and streaming of copyrighted content.

The tide, however, was blowing in favor of the pirate ships, with the flag of the free flow of information and culture flown by Berners-Lee himself, the movement’s sea captain and war captain. Alongside the inventor of the World Wide Web were the British Wikipedia and non-profit digital rights organizations such as Fight for the Future and the Electronic Frontier Foundation.

Riding the wave of free culture pirates was a group of commercial companies, most of them recently founded by young white people from prestigious U.S. universities. The new Internet privateers would soon be known by the nickname of big tech: promising technology corporations whose financial resources were already, in 2012, facing the doubloons invested by the old cultural industries in the legalized market of the U.S. Congress’s lobbies.

More evident than the economic dispute in the corridors of Washington, however, was the battle fought in the field of ethics. Faced with the maximization of intellectual property rights, which was demanded by old corporations such as Warner, Disney, Universal, and Sony, the new Internet companies resorted to the tarot of universal human values to pull the cards of freedom of expression and the right of access to information, but personifying the figure of guardian paladins of art, culture, and diversity. Before the arrival of the digital outsiders, such a character was embodied precisely by the film and phonographic industries, which enjoyed enormous prestige and prominence since the conquest of the American Wild West, enrapturing hearts, minds, and pockets with their films and records.

This idyll, though, is beginning to suffer turbulence with the development of digital technology, which makes it possible to enhance what Walter Benjamin called the technical reproducibility of the work of art. The new possibilities of copying, reproducing, and sharing cultural and information content through the Internet have become, in the 21st century, a threat to the business models built around the exploitation of copyright.

For the defenders of the free flow of information on the network, such models represent immobilism, petrification, the strangulation of circulation; at the limit, the death of culture. The cultural industry discourse, on the other hand, emphasizes the harm allegedly suffered by millions of people employed directly or indirectly in the sector’s production chains, and gives the nickname of pirate (a category with great moral weight) to all those who copy, share or make available digital copies of content protected by intellectual property and copyright laws.

In addition to the moral offensive, associations of the phonographic and film industries began to take legal action against consumers of downloadable music and movies, suing thousands of people in the 2000s. This process contributed to eroding the public image of record labels and Hollywood studios and undermining popular support for the 2012 anti-piracy bills.

Defeated, albeit temporarily (as history would show in later deals between the cultural industry and streaming platforms such as Netflix, Spotify, and the pioneering YouTube), the music and film industry associations accused Internet companies of using their platforms to incite American public opinion against the bills.

On the day the Internet came to a standstill, Google’s homepage, for example, displayed a large censorship bar covering its well-known logo; clicking on it took visitors to another website containing information and the petition against SOPA and PIPA. At the time, the movements for the free flow of information and culture saw no problem with this, because the cause was noble: it was about defending freedom on the Internet.

The ideological mask of the big tech companies falls when, after 11 years of the resurgence of hate speech, disinformation, and environmental and scientific denialism on digital networks, the Brazilian Law of Freedom, Responsibility and Transparency on the Internet (PL 2630) is finally scheduled to be voted on.

On the eve of the vote, in May 2023, the modus operandi of 2012 was repeated: Google’s homepage displayed the phrase “PL 2630 may increase confusion about what is true or false in Brazil”; Spotify issued an ad with the same phrase, but in audio; YouTube spread misinformation about PL to content creators on the platform, even promoting a hashtag against the bill; and Telegram sent its millions of Brazilian users a message saying that “Brazil is about to test a law that will end freedom of expression.”

History shows that, whether in the past or in the present, the motivation of the big tech companies remains the same: it has never been freedom, but liberalism. It has never been the defense of accessible communication and the exchange of information between individuals, but the defense of business models free from any kind of regulation or oversight. In 2012, this was still not clear to many people; in 2023, it can no longer be hidden.

*Translated from Spanish by Janaína Ruviaro da Silva