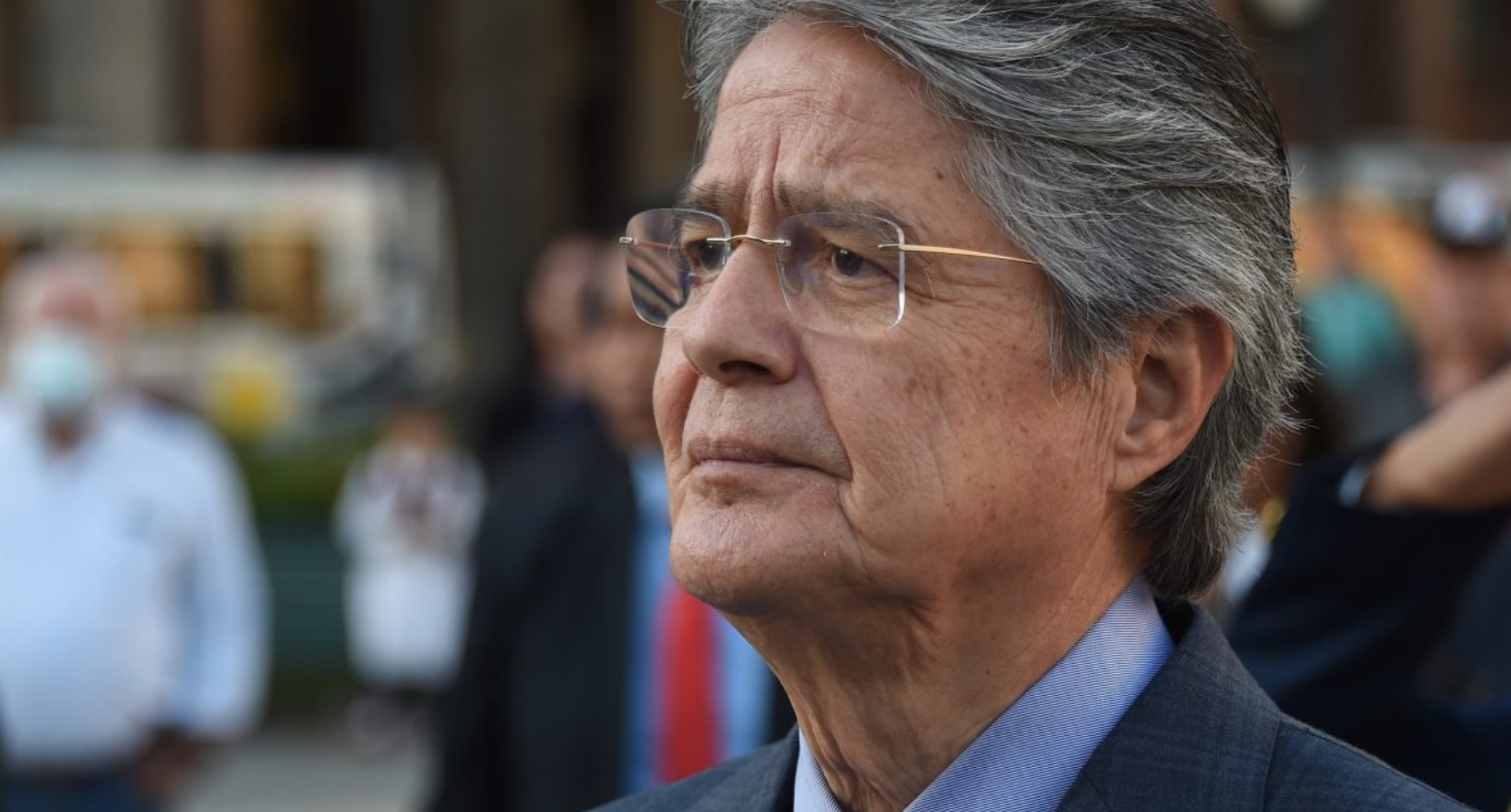

The President of Ecuador signed on Wednesday morning, May 17, the decree to dissolve the National Assembly, thus applying for the first time Article 148 of the Constitution that was approved in 2008. This instrument, known as “mutual death“, is created to unblock institutional conflicts between the functions of the state, particularly between the Executive and Legislative powers. The idea of the constituents when drafting the Constitution was to shield the president and prevent his possible arbitrary removal at the hands of unappealable legislative majorities.

The mutual death mechanism is the power of the President of the Republic in the event of a situation of “serious political crisis”. The characterization of this situation is left to the judgment of the president and does not require the qualification of any other government body. It is a feature of Ecuadorian hyperpresidentialism, which, however, applies principles of parliamentary democracy by forcing new elections when the conflict between the Executive and the Legislature hinders government action.

The application of mutual death closes a cycle of political conflict between the Executive and the Legislative and opens another with the renewal of the authorities in both functions of the state. The Constitution states that the National Electoral Council must immediately call for elections for president and assembly members to complete the remaining term of office. According to the terms between the call, the election, and the appointment of the new authorities, a period of no more than six months is foreseen, in which the current president will govern without a legislative body and will be able to approve, by decree, laws of economic urgency, but with the prior qualification of the Constitutional Court.

This will be a period in which the Government can do its work without any obstacles or restrictions from the National Assembly. During these months, the ruling party and its coalition have the possibility to reconfigure their lines of action and strengthen themselves with respect to the elections, in which the current president is expected to seek ratification of his mandate.

The consequences of this juncture for the other political forces are differentiated. What for some is an opportunity, for others is a serious affectation. This is the case of the traditional right-wing party, the Social Christian Party, an ally of Correism in the impeachment of President Lasso, which saw itself in a situation of strengthening if the president was removed from office. The rise of the vice president to the new magistracy could have meant a rapprochement with a government possibly closer to his political tendency.

The Social Christianity Party has come out badly from its alliance with Correism. In the last elections, it lost the Mayor’s Office of Guayaquil, its historical political stronghold, but its setback is notorious throughout the country, and it is no longer an option for the Presidency. It will surely face a reduction in the number of representatives in the next National Assembly.

The other parties of the center left, Pachakutik and Democratic Left, which seemed to have recomposed their ranks in the last elections, are also victims of their rapprochement to Correism. The splits of sectors attracted by the strength of the Correa’s majority in the Assembly disarticulated all their projections. The figures who were behind their electoral success (the presidential candidates Yaku Perez and Xavier Hervas) no longer militate in their ranks. The leadership of Pachakutik is in dispute and the movement is under siege by the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador (CONAIE), the historical organization of the indigenous peoples, which wants to take total control of it.

This is not the case for the Union for Hope (UNES), the party of Correism, which has led the impeachment strategy and which emerges from this situation relatively unscathed. On the one hand, it suffers the effect of the dismissal of the Assembly where it had consolidated its absolute dominance, but, on the other hand, it emerges as the best-positioned force for the next election. The fragmentation of the opposition may favor him in the presidential and legislative elections. His challenge to mutual death has been lukewarm, as he was preparing his forces for possible elections.

Although mutual death is a constitutional and legal procedure, its application is unprecedented in the constitutional history of the country, which generates profound uncertainty. Once again, the institutionality is put to the test and is forced to demonstrate its capacity for containment.

Two entities will be fundamental for the conduction of an enormously complex political process: the Electoral Council and the Constitutional Court. The Electoral Council has the task of organizing in a short time a transparent and efficient electoral process but in a tense political scenario. For its part, the Constitutional Court, which will have to monitor the actions of the Executive so that they do not exceed the constitutionally established parameters in the absence of a legislative body to supervise its performance, also will have to qualify the constitutionality of the economic emergency decrees to which the Executive may resort and which become its main instrument of management and legislation. The operation of setting clear limits without intervening as a political actor in the process could consolidate this institution as the most important guarantor of democracy and constitutional rights.

It is foreseeable that the Council for Citizen Participation and Social Control (CPCCS), a body that should be characterized by its non-partisanship and which recently renewed its composition, could introduce turbulence in the political process. The CPCCS is clearly aligned with Correa’s supporters and has declared that it intends to substitute the legislature in its oversight task. It is very likely that Correism will try to use this organization as a pivot to regain power.

The application of mutual death in Ecuador will demonstrate whether it is useful as an escape valve for political tensions between state functions, beyond being conceived as a pure shield against hyperpresidentialism. If it works, the countries of the region will have an important lesson to apply to their own institutional designs.

*Translated from Spanish by Janaína Ruviaro da Silva