The results of the elections of February 5 in Ecuador generated a political earthquake that altered the balance of power and reconfigured the scenarios for the second half of President Guillermo Lasso’s term. Two major political agendas came into play in this consultation: on the one hand, the elections of sectional authorities, mayors, and provincial prefects, as well as members of the Citizen Participation Council; on the other hand, the eight questions of the consultation or referendum on security, institutionalism, and environmental protection issues. Two lines, which, combined, were going to produce more than confusion not only because of the technical-legal complexity of the questions but also because of the possible use or political instrumentalization that they could suffer as they were inserted in an electoral process in which forces were fragmented and with a tendency to polarization.

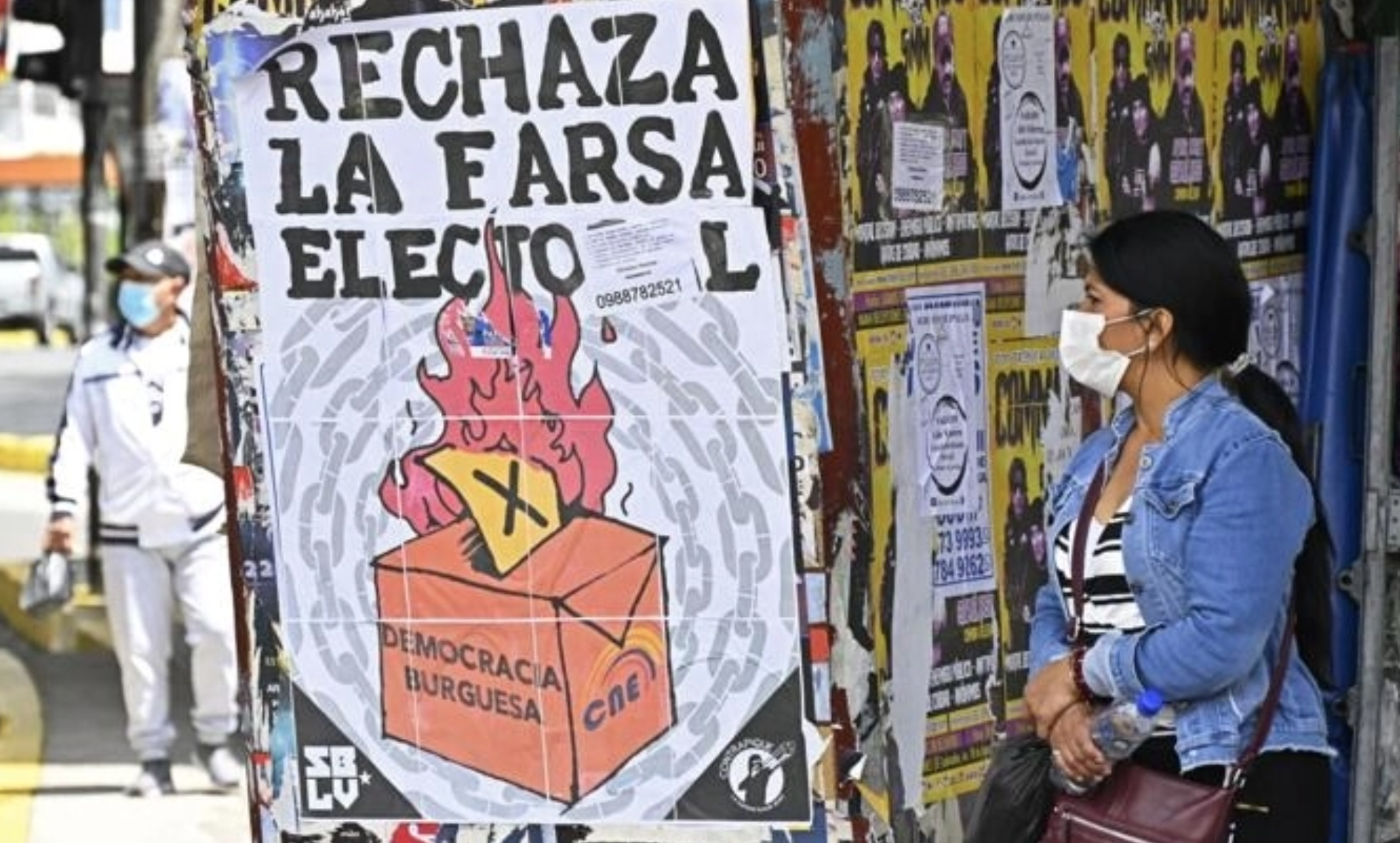

Every popular consultation has a plebiscitary component on the government’s management, particularly when it is the one who calls for it. The inclusion of the consultation on highly sensitive issues for citizenship, which was expected to be easily approved, led to think that the hidden objective of the Government was its own legitimization. The issues were of enormous relevance and for many sectors, they opened the possibility of discussing necessary aspects of political reform. The challenge then was to prevent the plebiscite line on the government’s management from placing the debate on the consultation questions in the background, but the vortex and the vertigo of the elections would be responsible for phagocytizing them.

In the eight questions of the consultation, the results are negative for the Government, although the margin of difference is not substantially high. In question, referring to extradition in cases of transnational crimes, the “no” is higher, but with a small margin of 2%. Questions 5 and 6 aimed at recovering the Assembly’s capacity to appoint control bodies, as well as the reduction of the size of the Assembly itself and the regularization of local political organizations. Here, the margin of difference does not exceed 10 points on average.

The same happened with the electoral result. The triumph of the opposition is generalized and broad throughout the country. The movement linked with former President Rafael Correa won prefectures in the four most populated provinces (Guayas, Pichincha, Manabí and Azuay), as well as the mayoralties of Quito and Guayaquil. The participation of the governing party was completely marginal, which confirmed the lack of organizational support for the regime. It is also probable, and perhaps for this very reason, that the Government put all its energies into the consultation, but neglected the presence of its political support.

The result, however, is still surprising. Several opinion polls registered a few days before the electoral event a high approval of the consultation issues. It seemed that the situation showed the growth of a genuine debate among the different options presented, but the tendency to polarization, typical of the electoral confrontation, tended to superimpose itself on the deliberative dynamics. The inevitable contamination between the object of the consultation and the temptation, both on the part of the regime to use it to re-legitimize itself and on the part of the opposition to weaken the Government, ended up taking away any sense from the institutional reform proposal.

Triumphalism is not a good advisor: it generates the impression that power has no limits. As soon as the electoral count was completed, former President Rafael Correa proposed the possible removal of President Lasso before the end of his term, a proposal that is echoed by the maximalist positions of the Citizen Revolution installed in the National Assembly, which could set in motion the impeachment proceedings and the removal of the President. On its part, the Government was led to a virtual dead end and could opt for the cross-death expedient: which consists of the Assembly’s dismissal and call for early elections of the President and Assembly members within six months.

The outlook is not yet very clear. On the one hand, it remains to be seen whether the appetite of Correa’s maximalism to seize power, without respecting the margins imposed by the Constitution, will prevail or, on the contrary, whether it will opt for maintaining the stability of the regime and postulate the replacement for the presidential elections of 2025. For the elected authorities of the same Correism movement, a serious crossroads is presented: to present management results in short terms to placate the citizen demand or to work according to the interest and hunger for power of their charismatic leader.

The lessons learned from the results of both the consultation and the elections are very significant: the need to be clear about the scope and limits of the consultation as a means of direct democracy. Surely, the plebiscite option is not very advisable to deal with transcendental issues of institutional redesign, which require smaller doses of politicization and political passion, even worse when it is done in the context of an electoral process in which the considerations and immediate calculations of the conjuncture are dominant.

The result of the consultation indicates that the institutional reform remains valid and is an important leitmotiv for broad sectors that voted “yes”. Surely, in the medium term, this demand will come up again. What is difficult to predict is the outcome of the current situation: it remains to be seen whether the Government still has the strength and sufficient political intelligence to make a 180-degree turn and modify its policy lines that have exacerbated social and economic asymmetries and, on the other hand, whether Correism can demonstrate its commitment (or not) to strengthening democracy and its institutions.

In 2007, the Movimiento de la Revolución Ciudadana swept away all democratic institutions in the name of the need to refund the state. Now, with their own Constitution in force and almost unchanged, what would be the justification for violating the order they themselves created?

*Translated from Spanish by Janaína Ruviaro da Silva