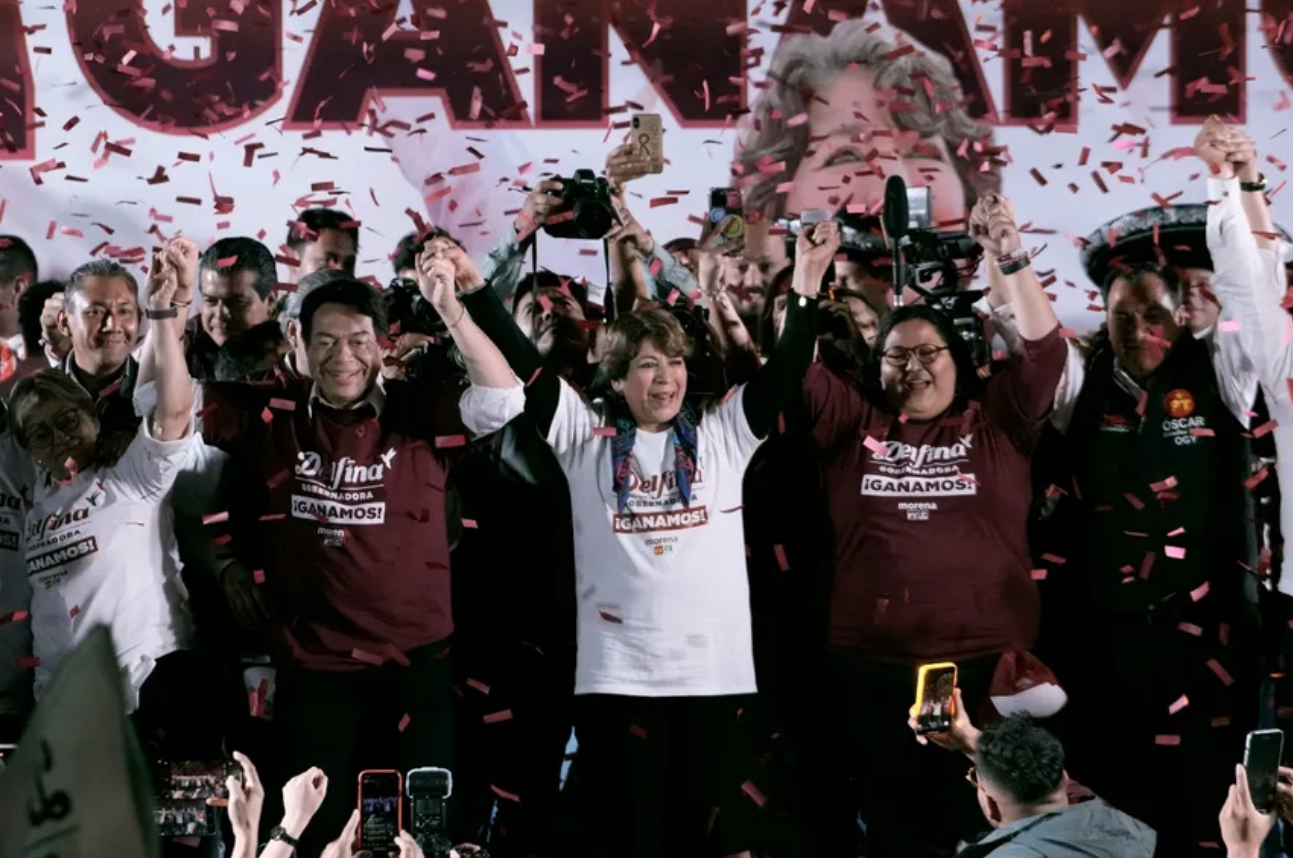

According to preliminary data from the state elections of Sunday, June 4, the common candidacy, led by the Morena Party, won the governorship of the State of Mexico and defeated the PRI-PAN-PRD-NA electoral alliance by more than eight points. The triumph in the State of Mexico, the entity with the largest number of voters (12.7 million) and where the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) has governed for more than 90 years, reinforces the successes of Morena, which already has 23 federative entities. This positions it as a favorite for next year’s elections, when the Executive power, the federal Legislative, different governorships, local Congresses and municipal presidencies will be renewed.

The election in the State of Mexico was a demonstration of how political parties skip the rules and compete for power within and outside legal deadlines. The competition for the candidacy of the State of Mexico began openly more than a year ago, outside any legal deadline. The candidates aspiring to the governorship, professionals in politics, promoted themselves with graffiti, advertisements with their images and interviews in the media, among other resources.

Since the electoral authorities did not call for votes or discuss their real aspirations, there was no sanction from the electoral authorities. Neither is it known where the resources came from nor is there an estimate of the amount of money used for such promotions. The paradoxical thing is that the legislation defines the limits for the pre-campaigns, in which the aspirants to the candidacy can participate, the limit of the money that can be spent and the access to the media.

For the election, only two single pre-candidatures had been registered, the one led by Morena, together with the PT and PVEM, and the option of the PRI and its allies. The parties left the pre-campaign stage without internal competition; instead, they tolerated the promotions of some of their militants outside the legal deadlines.

From the beginning of the campaigns, the different measurements of voting intentions showed an advantage for Morena’s candidate, Delfina Gómez, over the PRI’s candidate, Alejandra del Moral. The margin among pollsters varied from a supposed technical tie with a 3% difference to a Morena advantage of 30 points.

The poll results were part of the campaign narrative. However, there are three pieces of information that were consistent in the measurements. The desire for change (alternation), the refusal to vote for the PRI, the approval of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador and the low approval of Governor Alfredo del Mazo Maza.

Given this information, the campaigns were not very disruptive, even when negative campaigns were presented on social networks. The leading candidate, Delfina Gómez, dedicated herself to managing her advantage, while the candidate in second place, Alejandra del Moral, tried unsuccessfully to present herself as a change to the government and the party to which she belongs. During the only two debates held, there were no major confrontations, neither of their proposals nor of their political trajectories. The political parties and the electoral authority had decided that the debates would be in rigid formats, in which the candidates dedicated themselves to reading most of their messages.

The election results leave important challenges for the political parties. The PRI has not carried out, for now, a self-criticism that would allow it to diagnose its recent defeats. Nor can it visualize a path that would allow it to be competitive in the short and medium term. Leaders prefer to fill auditoriums and blame each other rather than re-found themselves as a political party.

The alliance with its former political adversaries, the PAN, and the PRD, does not cease to be circumstantial and electoral. For Morena, the immediate challenge is to reconcile the beginning of a government different from the PRI, at the same time as the political effervescence for the candidacies for next year’s elections. Morena has an inheritance from the Mexican political left, factionalism, which translates into an intense internal struggle among the different groups that many times prefer to lose the election rather than appeal to the union with opposing factions.

In politics, it is complicated to win elections, especially if you have adversaries within your own party.

*Translated from Spanish by Micaela Machado Rodrigues