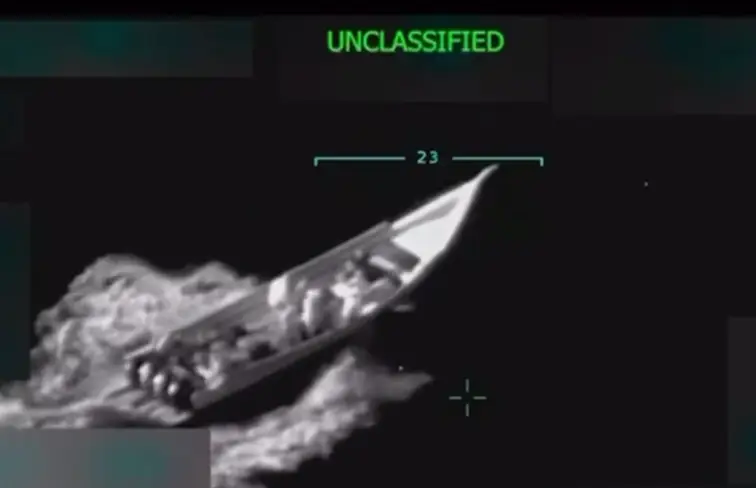

On September 1, 2025, a Venezuelan boat was destroyed by military forces of a United Nations member state in international waters of the Caribbean Sea. The attack, confirmed by President Donald Trump, left eleven people dead. The vessel was allegedly linked to the Tren de Aragua criminal group and drug trafficking. However, the operation was carried out without multilateral authorization or a formal claim of self-defense. The incident has reignited a debate that goes beyond technicalities: can a state exercise lethal force outside its jurisdiction without violating international law?

This episode occurred in a space that belongs to no country, raising growing tension between security and legality. In a world where threats move across borders, how should states act without undermining the international legal order?

What does international law say?

International waters (also known as the high seas) are governed by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). It establishes that no state has sovereignty over them, and that all enjoy freedom of navigation, fishing, and overflight. But this freedom is conditional: Article 88 reserves the high seas for peaceful purposes. The use of military force, therefore, is only permitted in exceptional circumstances.

Vessels sailing on the high seas are under the jurisdiction of the state whose flag they fly. They may only be inspected if there are well-founded suspicions of piracy, slave trafficking, or if they are stateless. In addition, the use of force is limited by the UN Charter, which allows it solely in self-defense against an armed attack, provided it is immediate, necessary, and proportionate.

In the recent case, no claim of self-defense was made, there was no Security Council resolution, and it was not demonstrated that the boat was pirate or stateless. Therefore, the legality of the action is questionable. The high seas cannot become a lawless zone where each state acts at its own discretion.

What is national security?

In parallel, the notion of national security has evolved in recent decades. It now includes threats such as drug trafficking, terrorism, and organized crime. This expansion has led some governments to justify extraterritorial actions in the name of security. But such logic can erode fundamental principles of international law, such as the prohibition on the use of force and respect for state sovereignty.

The international responsibility of a state is triggered when it violates legal obligations, such as the unauthorized use of force, the infringement of another state’s sovereignty, or the violation of human rights. In this case, the fundamental rights of the boat’s occupants, especially the right to life, may have been violated. Moreover, there is no evidence that mechanisms of regional cooperation or mutual legal assistance, such as those provided for in the Convention against Transnational Organized Crime, were exhausted.

The fight against drug trafficking cannot become an excuse for unrestricted use of force. State actions must be guided by the principle of proportionality and the duty of due diligence. Acting outside one’s own territory, without multilateral mandate and without legal safeguards, weakens the international order and opens the door to abuse.

From a legal perspective, the destruction of vessels on the high seas without multilateral authorization is not permitted. Customary international law and existing treaties recognize only three exceptions: self-defense, authorization by the UN Security Council, and previously agreed multilateral operations. Even in extreme contexts, such as the fight against piracy in Somalia, specific resolutions were required to allow military action.

Without these conditions, any intervention is considered unilateral and may violate principles such as non-intervention and respect for life. In the recent case, the absence of legal justification makes the act a controversial measure with significant legal implications.

Revisiting international law

This incident forces a reconsideration of the role of international law in transnational security contexts. Can the law adapt to new threats without losing its protective essence? Are we witnessing a functional reinterpretation of the principle of non-use of force or its gradual erosion?

International legality is not an obstacle but a guarantee. Security must be exercised with responsibility, transparency, and respect for human rights. The question is not whether a boat can be destroyed on the high seas, but how to construct a legitimate, effective, and law-abiding response.

The ocean has historically symbolized freedom, trade, and encounters. But it can also become a stage for tension, fire, and silence. When a vessel is destroyed on the high seas and eleven people lose their lives without trial or verification, international law faces its greatest challenge: to remain relevant.

This text does not seek to issue verdicts. It seeks to raise questions. Questions that unsettle, that hurt, that demand serious legal answers. Because if the law cannot protect those navigating unflagged waters, then the sea ceases to be a shared space. And that, beyond any border, concerns us all.

At sea, the law must be the only anchor. Without it, what floats is not justice but uncertainty.

*Machine translation, proofread by Ricardo Aceves.