In 2018 Mexicans voted for Andrés López Obrador, a disruptive candidate whose speech pledged to break with traditional politics and favor the most disadvantaged people. Since then, a series of constitutional reforms which have been driven, rather than encouraging the debate and the construction of agreements, deepened political polarization.

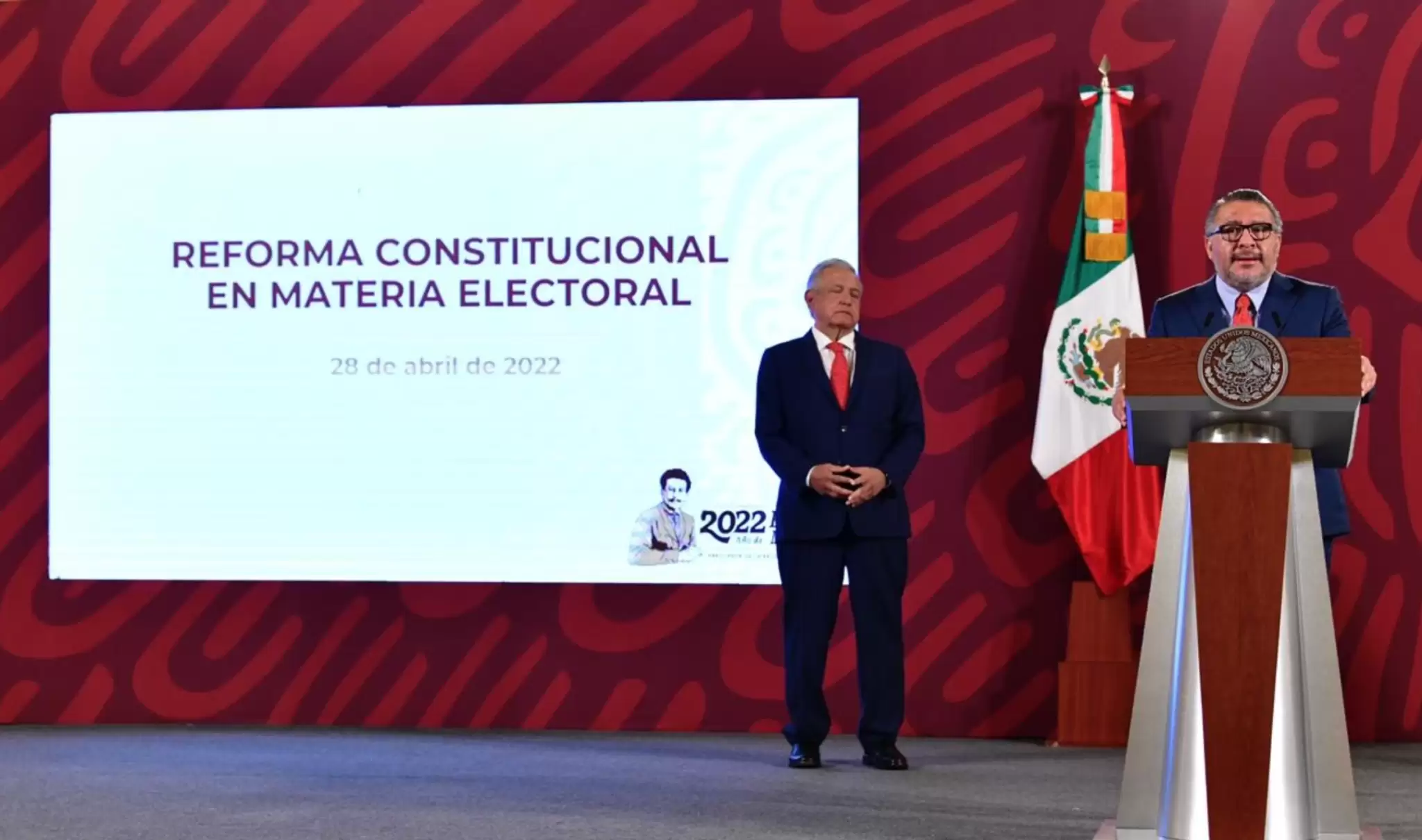

Recently, the ruling party “revived” an initiative for a fundamental political-electoral reform. One of its core points is to substitute the National Electoral Institute (INE) for the National Institute of Elections and Consultations (INEC), to reduce the number of electoral counselors from eleven to seven and that they are proposed by the powers of the Union and elected by popular vote. This reform includes the Electoral Tribunal of the Federal Judiciary (TEPJF).

The project also includes abolishing the “Organismos Públicos Locales Electorales (Oples)”, which are responsible for the organization of the elections in their federal entity, as well as the local courts, so that all electoral administration and justice will be congregated in both the INEC and the TEPJF.

On the other hand, the reform suggests a new configuration of the chambers of Deputies and Senators, reducing the number of deputies from 500 to 300 and senators from 128 to 96. In addition, these legislative figures would be elected by the pure representation system, in other words, based on the percentage of votes obtained. And, at the same time, it is intended to include the members of the town halls in the local councils.

The reform also proposes the elimination of regular financing to political parties, which would limit the flow of prerogatives exclusively to electoral periods. Likewise, it seeks the implementation of electronic voting and the reduction of radio and television broadcasting in electoral matters.

How do we understand this reform?

The reduction of the budget for political parties (not its elimination), the implementation of electronic voting, the reduction of the number of members of Congress, and making spending on electoral processes more efficient, without compromising their quality, are positive aspects of this initiative.

However, the reform should strengthen the quality of elections and guarantee the access of all people to elective positions through the crystallization (to reach constitutional rank) of affirmative actions that both the INE and the Oples have driven in favor of historically marginalized segments of the population. Violating rights by restricting the participation of candidates in the structure of the highest national deliberative body should be avoided with the continuity of open calls, however, the requirements and the evaluation process should be reviewed.

One aspect of the proposal that should be analyzed in detail is that of reducing the number of electoral offices. If the criterion is financial, the new workload that this new body will have to face should be weighed. But in case the proposal to create the INEC was to prosper, a matter that is not easily visualized within the Congress, it would be important to uphold the stepped renewal of its members and not to violate the right of anyone to participate, except in the cases established in the norm.

It is also essential to rethink the financing of political parties (from the minimum percentage to access the legal prerogatives), as well as to revise downward the formula for the allocation of resources. In addition, when entering into fundamental reforms, it would be necessary to regulate the distribution of these resources internally, that is to say, to prevent political parties from becoming white elephants loaded with heavy payrolls and losing the meaning of these groups: to make politics.

Regarding the disappearance of the Oples proposed in the official initiative, it is critical to review their operation. Starting from the local level, there have been numerous outstanding policies in favor of women, people with disabilities, indigenous people, youth, senior citizens and sexual diversity, among others, as well as the use of the electronic ballot box and, in specific cases, the organization of elections by indigenous normative systems.

In turn, the project does not tacitly state what will happen with the local elections governed by Indigenous Normative Systems, also known as “Usos y Costumbres”. Oaxaca, Chiapas, and Guerrero have municipalities governed by this system, and it is the OPLE that knows and validates their elections. In Oaxaca alone, 417 municipalities use this system.

However, the INE does not have a specialized area to review these cases and has opted to leave it in the hands of local authorities – therefore, its experience in the matter is limited. So, where are the rights of indigenous communities to elect their governors?

On the other hand, if the electoral reform is carried out, there will be important savings in the organization of local elections with the implementation of the electronic ballot box and the reduction of parties prerogatives. The Oples can assess the double financing received by the parties (national and local) and the return of citizen councils, or protect the number of members and recess times, always reviewing the particularities of each federal entity. Savings at the local level are in reviewing the double-party prerogative.

Another measure that may be worth analyzing is to create a formula for the allocation of resources to the Oples, taking into consideration factors such as the nominal list and the number of elections to be organized in the fiscal year.

Regarding the reduction and the way of electing deputies and senators, as well as the reduction of local congresspersons and city council members, a thorough analysis is needed to evaluate the benefits and disadvantages. The idea of homogenizing processes, assignments, and attributions is interesting, as long as the intention has no other purpose than to strengthen the electoral system. The autonomy of these State bodies must be safeguarded.

In conclusion, a political-electoral reform must adjust to the healthy competition of participants, take care of and strengthen institutions and evaluate what can be improved. Much can be saved if there are coordination synergies, if attributions are reviewed and processes are simplified. The key lies in the willingness of the political forces to compromise. If so, a constructive reform can see the light for the 2024 elections.

*Translated from Spanish by Camille Henry

Autor

National Coordinator of Electoral Transparency for Mexico and Central America. Master in Governance, Political Marketing and Strategic Communication from King Juan Carlos University (Spain). University professor.