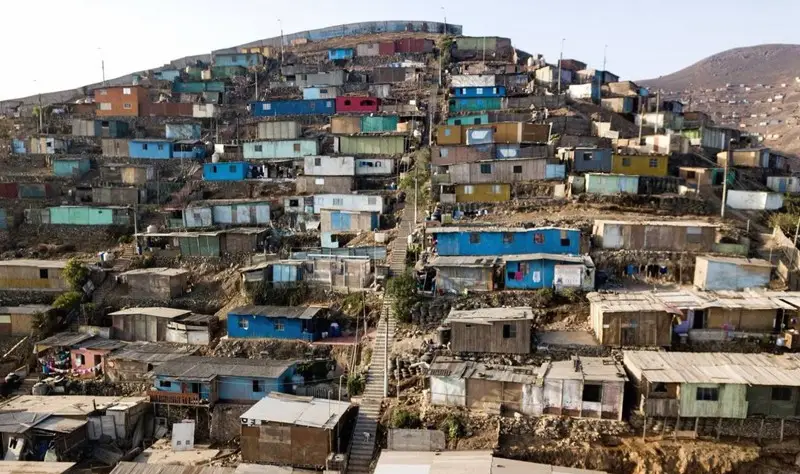

In recent decades, the world has seen rising inequality, with 2023 being labeled by the World Bank as “the year of inequality.” An increasing share of income and wealth is concentrated in the hands of a few, leaving a shrinking portion for the majority, which includes a massive pocket of poverty. According to the United Nations, “More than two thirds of the world’s population today live in countries where inequality has grown.” Yet, beyond the data, how do those affected actually experience this inequality? A recent survey by the Instituto de Estudios Peruanos and OXFAM sought answers from Peruvians, collecting responses from a nationwide sample of 1,508 interviews.

Peru ranks as the fourth most unequal country globally, according to available analyses. The IEP-OXFAM survey found that half of respondents (51%) perceived the country as highly economically unequal. Meanwhile, a quarter (27%) believed it was “not very unequal,” and 7% astonishingly claimed it was “not unequal at all”—with this latter view most common among the poorest respondents.

When asked to qualify economic disparities, slightly more than half (56%) said that “the income differences between the rich and the poor are too large.” Contrarily, one in four (27%) did not see these differences as excessive. By examining the responses across social strata, the survey revealed that perceptions of these disparities as excessive were higher among the upper strata (69%) than the lower strata (48%). In other words, those who thought the differences between rich and poor were not too large were more prevalent among the lower strata (33%) than the upper strata (15%).

An accepted poverty

Peru is a country where, according to the World Bank, “seven out of ten people are poor or vulnerable to falling into poverty.” Correspondingly, the survey showed that more than half of respondents (54%) said their income was insufficient, while 14% claimed to have enough income to save. Despite this, half of those surveyed believed that “In Peru, a poor person who works hard can become rich,” 38% said that “Everyone in Peru has equal opportunities to escape poverty,” and a nearly identical proportion (37%) thought that “Poor people are poor because they miss opportunities.” None of these three statements were rejected by a majority.

Responses to the assertion “In Peru, a poor person who works hard can become rich” showed approximately equal support (50%) across all social strata. Higher agreement rates were noted among respondents aged 18-24 (58%), self-identified “white” individuals (57%), and those politically aligned with the right (59%).

Several findings point to a degree of acceptance of various forms of inequality. This is evident in how respondents rated the severity of different inequalities. In lower strata, economic inequality was viewed as less severe. Meanwhile, gender inequality was deemed “serious” by one in four (24%), but 30% called it “not very serious,” and 17% said it was “not serious at all.” Overall, almost half (47%) saw no significant issue with gender inequality. Similarly, in a country frequently labeled as racist, the inequality between white and non-white people was considered “serious” by only 23%, while 22% found it “not very serious,” and 31% viewed it as “not serious at all.” Thus, more than half (53%) did not perceive a major issue with racial inequality.

Inequality in access to work and services

The survey also revealed significant disparities in access to work and services. Over half (52.4%) considered job access to be “highly unequal.” Justice access had the highest inequality perception, at 75.5%, while education access stood at 52.7%. Surprisingly, in a country that recorded the world’s highest per capita COVID-19 death rate, only 66.3% of respondents said healthcare access was very unequal.

When asked about the most crucial factor for achieving a good position in Peru, 67% cited “having a good education,” reflecting the old adage “those who study succeed.” This belief persists despite the well-known reality of high unemployment, even among those with professional training.

Looking to the future, the survey asked: “How do you think the economic situation of your children will be when they are adults?” Optimism prevailed, with 81% believing it would be “better,” although 13% in the lower strata anticipated a “worse” future.

A mix of awareness and resignation

The data reflect the dominance of an ideologically skewed view over a reality marked by stark inequalities. Resignation appears to hold sway among the poor, who seem to blame themselves for their circumstances, believing they remain in poverty due to a lack of effort. This perspective stands far from creating an environment ripe for revolution or even social upheaval. The focus on “entrepreneurship” seems to have defused the threat to social order that poverty once posed.

This apparent acceptance of inequality, labeled in the survey as “tolerance of inequality,” became evident when respondents were asked, “To what extent is inequality acceptable in Peru?” Half (51%) found it “unacceptable,” while 30% considered it “acceptable,” with the rest choosing neither option. Inequality rejection was higher among the upper strata (61%) and lower among the poor (48%).

Interestingly, this “tolerance” does not overlook power disparities. Two-thirds (67%) agreed that “The rich have too much influence over decisions affecting the country,” and 90% believed that “The country is governed by a few powerful groups for their own benefit.” As for potential solutions, 31% said that to achieve “a more equal country,” Peru needs “a fairer State.” Other answers garnered lower support. Additionally, respondents suggested that increased tax revenue should primarily fund education (32%) and healthcare (28%).

Despite Peru’s stark poverty, evident in credible measures, there seems to be little sign of the rebellion anticipated by subversive movements four decades ago. On the contrary, among the poorest, hope appears to rest on individual effort and, to some extent, support from a State that remains more ineffective and corruption-ridden today than ever.