The most unusual and singular presidential election in the world will take place in April next year. Not in some remote, underdeveloped country in Africa or Southeast Asia, nor on an oceanic island with an unpronounceable name. It will happen right here, in the heart of the ever-unequal and colorful Latin America—Peru.

In mid-April, Peru’s National Jury of Elections (JNE), the country’s highest electoral authority, confirmed that 43 political parties have been authorized to participate in the 2026 general elections, having met the necessary validation requirements. By law, all of them are obligated to compete; otherwise, they will lose their registration, which, in plain terms, means their extinction.

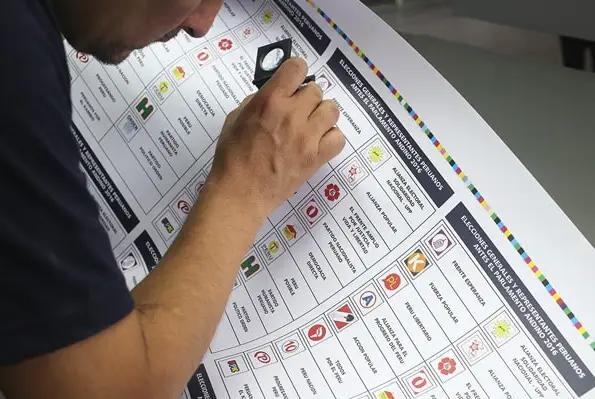

This means that next year, more than 27 million adult Peruvian citizens will head to the polls to choose a presidential candidate among 43 options. They will also vote for candidates for the Andean Parliament and for the bicameral Congress, from the same number of political groups. A logistical nightmare that will only deepen voters’ confusion.

Initial projections indicate that voters will receive a ballot approximately 65 centimeters long—the size of a 50-inch television. The list will even include the political party of Nicanor Boluarte, the brother of Peru’s own president, Dina Boluarte. Demanding neutrality seems difficult.

This record level of political fragmentation has a clear origin: in December 2023, the Peruvian Congress eliminated the PASO (open, simultaneous, and mandatory primaries), which had required parties to hold internal elections open to the general public—supporters or not. Previously, a candidate could only represent a party nationally if they had surpassed 1.5% internal support.

Now, parties will once again be free to choose how to elect their representatives in internal elections. It’s almost certain that they will grant this power to a group of delegates handpicked by the party leadership. An internal democracy in name only.

In 2026, Peru will also set a regional precedent by fielding 43 presidential candidates. For comparison, in 2023, Argentina held elections that resulted in Javier Milei winning the presidency, with just five candidates on the ballot—filtered by the PASO system implemented in 2009.

In Ecuador’s last presidential campaign, which ended with Daniel Noboa re-elected to serve four more years in the Carondelet Palace, 25 political parties participated in the first round. A high number, but nowhere near Peru’s.

Mexico elected Claudia Sheinbaum in 2024 among three candidates; Chile opted for Gabriel Boric in 2021 among seven contenders; and Colombia did the same in 2022, choosing Gustavo Petro among four presidential hopefuls.

Beyond the chaos of scrutinizing candidates’ resumes and proposals, the sheer number of parties in Peru’s race will likely push candidates into the runoff with minuscule shares of the valid vote—around 8% or 10%—jeopardizing both the representativeness and governability of the next head of state.

But as in all darkness, there’s a light at the end of the tunnel: electoral alliances. Emergency measures promoted by the Peruvian Congress now encourage coalition-building to reduce the number of parties. While alliances used to be penalized—requiring an additional 1% threshold for every party involved—now two-party coalitions need just 5% to pass the electoral threshold and keep their registration. If three or more parties join forces, the requirement rises only to a 6% cap.

Once the electoral process is officially underway, negotiations will begin. How many alliances will form? Can the scandalous number of eligible parties be significantly reduced? That remains to be seen… but one thing is certain: shell parties and political “rental wombs,” available to the highest bidder, will once again fish in troubled waters—while Peru continues to make history.

*Machine translation proofread by Janaína da Silva.