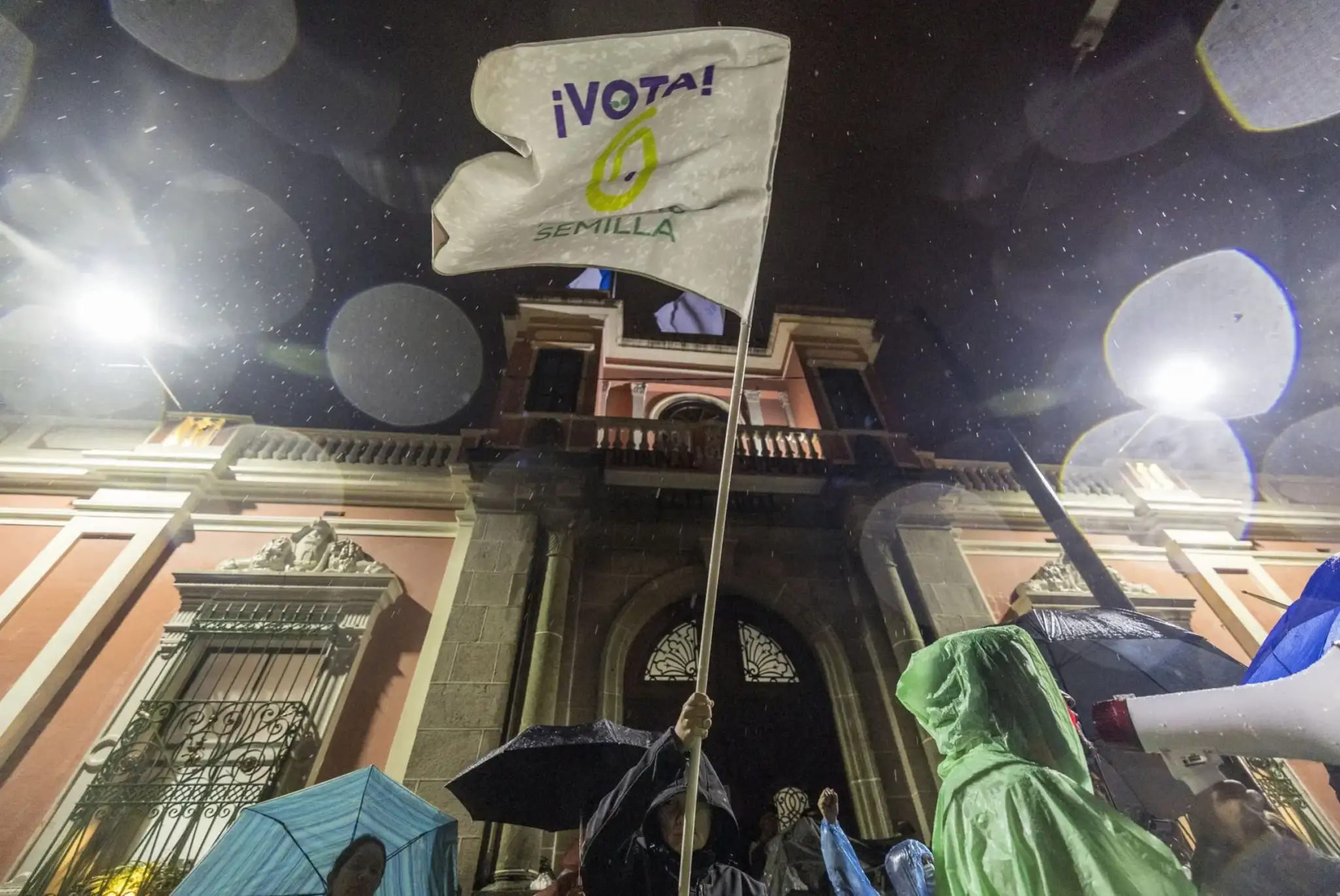

Three weeks after the first electoral round that positioned Sandra Torres and Bernardo Arévalo in the second electoral round unofficially, due to the lack of confirmation from the Supreme Electoral Tribunal (TSE), on July 12, a judge suspended the Semillha Party (PS). This happened after a criminal case promoted by the prosecutor Rafael Curruchiche, for alleged acts of corruption committed by presenting “false signatures”. This has been condemned by several political actors and the international community as it leaves Arevalo’s candidacy up in the air, since without a political party, he could not participate in the race.

These elections were an important challenge for Guatemala. It was expected that the country would overcome the democratic crisis suffered in the 2019 elections, from the organizational disaster of the electoral process, where even the Organization of American States (OAS), issued a severe report of findings regarding the electoral vulnerability of this Central American country.

For this, with a new conformation of the Supreme Electoral Tribunal (TSE), the hope was renewed of having an electoral process where certainty would be the constant in the feeling of political actors, their parties, powers, and candidacies. However, several events undermined confidence in the electoral organization.

In the first place, out of 23 presidential candidacies, some that apparently had high competitiveness indexes were eliminated, as is the case of Carlos Pineda, candidate of Prosperidad Ciudadana, who was “removed” from the race by the Constitutional Court, due to an injunction filed by Cambio Party, which challenged the internal election of the presidential candidate.

A poll published by the newspaper Prensa Libre at the beginning of May and carried out between April 14 and 23, gave Pineda more than 23% of voting intentions, ahead of Sandra Torres of Unidad Nacional de la Esperanza (UNE). Another case is that of former pre-candidate Roberto Arzú, who was disqualified for alleged acts of campaign anticipation.

In addition, months prior to the beginning of the electoral process, some conducts contrary to freedom of expression were informed, such as the imprisonment of José Rubén Zamora, a journalist who had pointed out acts of corruption by several political actors.

In the face of this climate of political instability and polarization, the elections were held on June 25, with the participation of just over 60% of those accredited to vote, in an atmosphere of calm and good electoral organization. Contrary to what happened in 2019, the electoral data and results transmission system worked and provided certainty and tranquility to the population in general. The Electoral Results Transmission Program (TREP) showed that the candidacies of Sandra Torres and Bernardo Arévalo would face each other in a second round to be held on August 20.

Acts after the election

In spite of the correct development of the election, certain subsequent acts began to cloud the process. The acceptance of a provisional injunction before the Constitutional Court to extend the contestation process and review the results, prevented the TSE from declaring the winning candidates, and therefore, from officially determining the celebration of the second round.

This intensified the climate of polarization and awakened the suspicion that the powers that be might have found the candidacy of Bernardo Arévalo, candidate of the Semilla Party, who has shown himself distant from the traditional politics of the country, uncomfortable. The candidacy of the social democrat has maintained a progressive discursive line. However, he had been inconsequential in the electoral polls.

However, in view of his rise and the crisis generated, Arevalo himself had manifested the attempt to subtract votes to favor the official candidate Manuel Conde or to delay the legal process so that he would be the one to choose the presidential binomial on January 14, 2024.

In fact, the international missions of Electoral Observation had insistently pointed out the weaknesses of the Supreme Electoral Tribunal (TSE) and the interference of the government in its decisions. To this was added the evident discomfort of some forces within the TSE for the electoral observation, specifically from the Department of strengthening cooperation, from where the work of several independent missions was blocked.

The question then is: What should be hidden from the international community?

*Translated from Spanish by Janaína Ruviaro da Silva