In 2025, Argentina is holding midterm elections. In the provinces, elections are being renewed, and on October 26, part of the chambers of deputies and senators will be renewed at the national level. In these elections, some opposition governors tried to separate their local election from the national one. The provincial elections are monitored by them directly; the national election is controlled by the government. Many governors did not want to join the October 26 national election out of fear that consensus toward Milei’s government would interfere in their territories.

One of the governors who managed to separate his election was the governor of the province of Buenos Aires, Axel Kicillof, a politician once propelled by Cristina de Kirchner but who has long been trying to build his own power, thinking about the 2027 presidential election on the one hand, and about being the candidate of the fragmented Peronism on the other, now that Cristina’s aura, along with her judicial situation, has faded, and with it, that of the once hegemonic Kirchnerism. It should be noted that the electoral roll of the province of Buenos Aires covers almost 40% of the national register, which makes its result a predictor of a consecutive national election.

Two months ago, in the midst of a political honeymoon with much of society, Milei’s government was confident of a comfortable victory in this first electoral test. Two weeks before the date, it began to speak of a technical tie. And finally, on Sunday, the political force of the governor of Buenos Aires obtained 47.33% of the provincial vote, while the ruling party obtained 33.45% of the vote. According to general commentary and media analysis, it was a crushing defeat.

Political analyses at the time and the media do not hesitate to point out the main variables explaining the defeat: controlling inflation at the cost of a brutal adjustment that began to impoverish the middle classes (the lower socioeconomic sectors, that is, poverty, hovers around 35% of the population), the abandonment of public works and the slow but progressive deterioration of physical infrastructure, the offensive against pensions, public health, and the national university system, the closure of small businesses and shops, the increase in unemployment, and job insecurity.

But another factor can be considered, one that has received diffuse and unfocused attention: Milei’s status as an outsider and, consequently, the political functioning of his government.

The political and communication literature of recent years has been devoted to commenting on and analyzing the emergence of political leaders who win elections but do not come from traditional parties or the political system itself. As Max Weber pointed out when characterizing charismatic domination, these politicians arise in societies and historical moments framed by deep crises. The contemporary world sees crises of various kinds in many countries, and, consequently, the rise to power of leaders alien to traditional politics: the outsiders.

The issue is that the literature has so far focused on describing the origins of these leaderships in different countries, their personalities, their environments, the measures they take, but not, at least not as a central variable, the political performance of outsiders. That is, the relationship between their political origin, the crisis they face when assuming power and—here I believe lies the issue—the quality of their political action in relation to the problems to be solved and the relationship they establish with the rest of the political system. On this level, I believe we can now speak of “bad outsiders” and “good outsiders.” Not good and bad in themselves, but in terms of the political results they achieve.

The “good outsider” is that novel leadership that surprises, that concentrates the legitimacy of power in a moment of crisis, that analyzes the central causes of the crisis and outlines the first measures but at the same time takes into account the collateral consequences of those measures, that calls upon experts or knowledgeable professionals on those problems, that begins to announce measures, many of them shock measures, that considers the means to implement them (whether laws, decrees, executive policies), that begins to weave alliances with part of the much-denounced traditional political system, that gradually communicates the steps to follow, that rejects opposition complaints with political—not vulgar—language, that tries to persuade rather than threaten, that surrounds itself with new political staff but within that ethical framework, that recalculates when faced with obstacles but does not try to advance stubbornly.

Of course, the “bad outsider,” especially the “very bad” one if he constantly crashes against reality, becomes enraged, and persists with insults and threats, is the exact opposite of what was just mentioned.

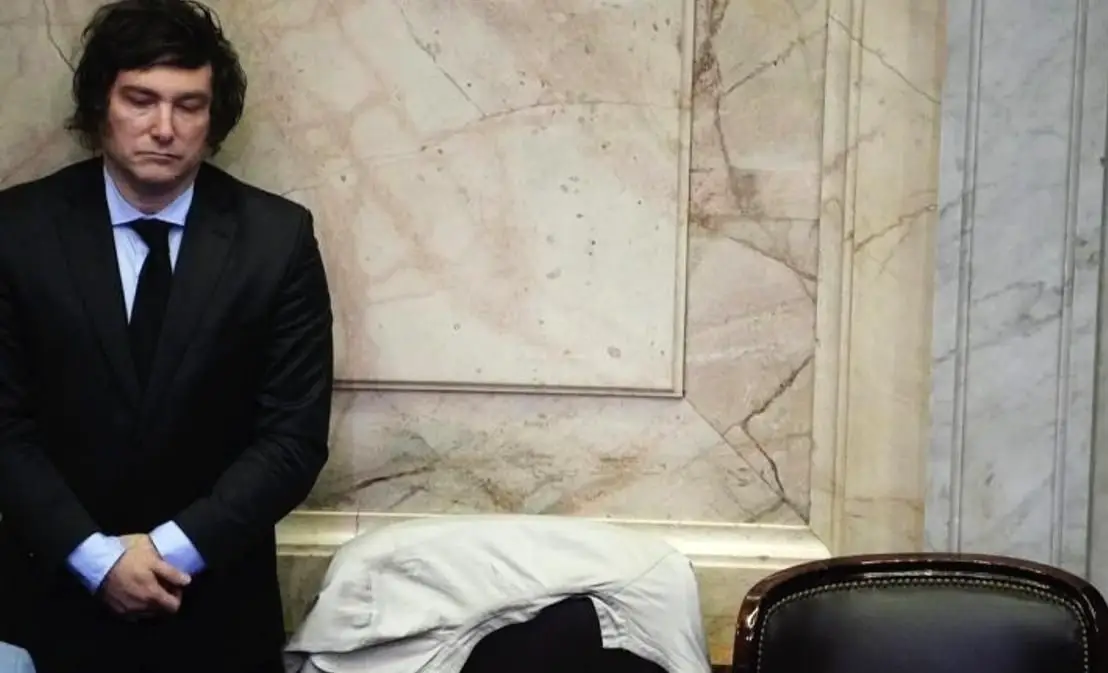

President Milei is a clear example of the “bad outsider.” Sunday’s heavy electoral defeat demonstrates this—provided he understands it and does not, as is his uncompromising style, attempt to double down by doing things the same way, with the same people, and the same political intolerance.

*Machine translation, proofread by Ricardo Aceves.