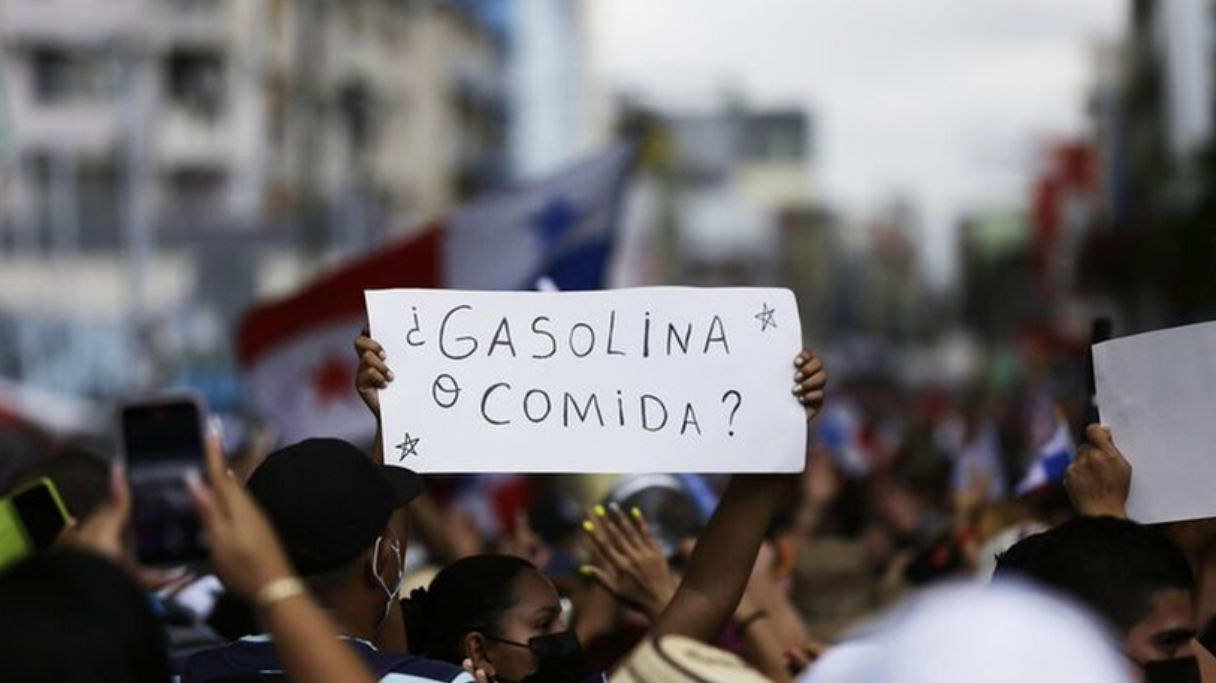

In July, in Panama, one of the places where protests were least expected due to its political stability, a powerful demonstration erupted as a result of the increase in fuel, food, and medicine prices (this also took place in the midst of a tense calm in the region). The mobilizations paralyzed traffic in different parts of the country for several days, preventing the transport of goods, which led to shortages of products.

Massive and heterogeneous support for the protests

Despite the economic impact, 3 out of 4 people support the mobilizations, according to an online survey conducted by the International Center for Political and Social Studies, AIP of Panama (CIEPS). This support contrasts with data from the latest Latinobarómetro report, which states that 9 out of 10 people would never participate in an unauthorized protest. This contradiction defines the protest as an unexpected and rare event in the country.

The protests have been led by a plurality of actors such as unions and social movements including doctors, teachers, construction workers, students, and indigenous groups. Although the demands are led by the National Alliance for the Rights of the Peoples (Anadepo), an organization that represents 20 groups of teachers, farm and fishing workers, transportation workers, and students, other groups such as the National Coordination of Indigenous Peoples (Coonapip) or the Single Union of Construction Industry and Similar Workers (Suntracs) also accompany the protests.

These actors constitute a heterogeneous network comprising different demands, in the manner of “the multitude” described by Antonio Negri and Michael Hard. Faced with this multitude, the Government decided to open several dialogue tables to address the different demands in different locations. However, the strategy failed and had to be abandoned.

After three weeks of protests, the parties were able to sit down (thanks to the mediation of the Church) in a single dialogue table, not free of ups and downs, conflicts, and controversies, but trying to recover political normality.

The causes of the protests

The trigger for the demonstrations was the increase in gasoline, food, and medicine prices, but, according to CIEPS survey data, corruption is the underlying problem that unleashed them. More than 6 out of 10 people think so, while the rest believe that the main reason is the cost of living. In fact, since mid-2020, CIEPS has been conducting different surveys, and in all cases, corruption has appeared as the main problem of Panamanian society.

Corruption is currently a huge dilemma in the country’s politics. It could be defined as a process that unifies a plurality of unsatisfied demands, product of clientelism, mismanagement of public funds, scarcity, inequity, inefficiency, “el juega vivo” (playing the game alive), etc. This diversity of factors comes together under the umbrella of corruption.

The data point to the fact that the rise in prices is “the tip of the iceberg”, but the insufficient attention to citizens’ demands, as well as the clientelistic management of public funds, constitute the underlying problems. But there is another major “liability” that has received less attention: the lack of policy.

Since 2017, the World Bank (WB) included Panama within the list of high-income countries, exceeding $12,055 gross national income per capita, data that brought it close to Eastern European countries. Between 2004 and 2018, Panama had an average growth of 7.0% compared to 3.3% in Latin America. This impressive growth has made possible qualitative and quantitative progress of the country, but it also leaves some “shadows”, according to ECLAC data, such as the inability to change the high degree of economic inequality, and the persistence of unequal treatment of different human groups is translated into 82.4% of people considering that there is discrimination in Panama.

The Panamanian development model has postponed these issues following “economic growth at the expense of politics”, as stated by experts Harry Brown and Clara Inés Luna. A model with successful macroeconomic performance, but which is currently in a very complicated economic juncture after the largest decrease in its history due to the measures to contain the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, for which it has had to face a historical social debt.

The moment of politics has arrived abruptly in the face of elites and power groups accustomed to political pacts and consensus that have been characterized as “transitional”. The current model no longer has the capacity to deal with dissent and antagonism. The irruption of politics and the imperative of turning it into an art of making possible what is necessary is one of the great tests that Panamanian society has ahead. And this will not be solved with new and creative technical solutions, but rather with political solutions that address the profound asymmetries suffered by the Panamanian citizenry.

Translated from Spanish by Janaína Ruviaro da Silva