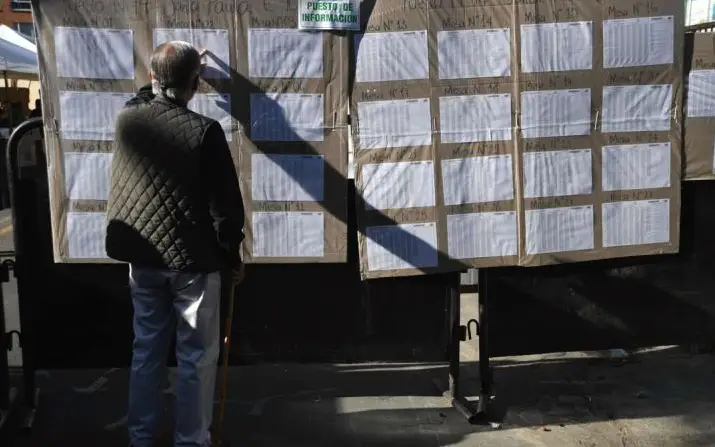

Despite fears of elections seriously affected by the wave of violence in Colombia, except for the tragic fire at the offices of the National Registry of Civil Status in Gamarra (Cesar) that cost the life of an official, Duperly Arevalo, and a few riots in some municipalities, in general, the regional elections of last October 29 passed peacefully and there were no serious allegations of electoral fraud. However, the profound disruption that our party system is undergoing is a source of great concern.

Suffice it to mention that in the recent elections, there were not only 36 political parties or movements with legal status, but more than 1,500. Let’s be clear: more than 1,500 “significant groups of citizens” (GSC) registered before the National Electoral Council (CNE) endorsed candidates for governorships, mayorships, departmental assemblies and municipal councils.

According to the highly respected Electoral Observation Mission (MOE), the number of GSCs has been increasing election after election. Between 2011 and 2019 alone there was a 488% increase (we went from 213 to 1,253 GSCs), which were formed mainly for the election of municipal mayors. And in the last elections the number of GSCs rose to the considerable sum of 1,500 created for the occasion, because, unlike parties, these groups have no vocation of permanence. They are a one-day flower.

If the minimum requirements to create a party or a political movement are laughable today (50,000 signatures or 50,000 votes, an elected parliamentarian), those required to launch a GSC are even more derisory. According to the current rules, the initial team of the virtual group – read well, a group – must be composed of at least three people, who must submit a form to the electoral authorities indicating the position (governor, mayor) or the public corporation (departmental assembly or municipal council) to which they aspire and the name of the candidates they will support, which must appear on the form for the collection of signatures. The signatures collected must be at least 20% of the result of dividing the number of citizens eligible to vote by the number of seats to be filled, up to a maximum of 50,000 signatures.

If the existence of 36 parties offering endorsements left and right is simply alarming, the hundreds of GSCs are already the last straw. According to the CNE, “the significant groups of citizens do not imply a permanent organization but the simple conjuncture of postulating lists and candidates in a given electoral contest” (CNE, 2019). In other words, one of the main functions that political parties should fulfill, the rigorous selection of candidates for elected office (for their experience, knowledge, and morality), has completely evaporated.

The figure of the GSC, which was created in not a good time by the 1991 Constitution, is, according to the CNE itself, an alternative to the political parties, since, according to a communiqué of the CNE, “the same Constitution enables the possibility that citizens who do not find affinity with the existing parties may exercise their passive electoral right, by nominating their names as candidates through this figure”. In short, instead of strengthening political parties — which today are going through a “bad time”— as the axis of representative democracy, Colombia has taken the path of accelerating their destruction.

And the mayor, who is around him?

In this context of an unlimited implosion of parties, ethnic and political movements, and CSGs, Colombia is experiencing not only an uncontrolled “endorsement market”, but a dark fair of hidden political financing. Indeed, several days after the October 29 elections, only a few parties, political movements and CSGs have submitted their campaign accounts to the CNE. It is likely that they still need to report their expenses. And, on the other hand, if they do, the weak CNE cannot oversee neither the transparency of the resources nor the authorized ceilings, or their use. Who can examine the accounts of 1,500 CSGs? Who can determine if behind the CSGs there are only obscure regional family clans dedicated to the plundering of public resources?

Plain and simple, the political party life is fading away at an accelerated pace. Its origin is to be found in the terrible institutional design in this field of the 1991 Constitution and in Law 130 of 1994, “whereby the basic statute of political parties and movements is dictated, norms on their financing and that of electoral campaigns are dictated and other provisions are issued”, in which two new and strange figures were created: the social movements with political aspirations and the GSCs.

Undoubtedly, the 1991 Constitution had a laudable objective: to overcome the perfect bipartisanship — that is, a system in which two parties obtain more than 90% of the votes and of the popularly elected positions to be filled — and to open the system for new political forces, in particular, those of the guerrilla groups that accepted between 1990 and 1991 to make the transition “from arms to politics”: April 19 Movement (M-19), the Popular Liberation Army (EPL), the Quintín Lama Armed Movement (MAQL) and the Revolutionary Workers’ Party (PRT).

However, this objective was tarnished by the lousy institutional design that led not only to weakening the existing parties — today the Liberal and Conservative parties are a mere shadow of the past — but also to fracturing the entire field of political representation into a thousand pieces. Today, the functioning of the collegiate bodies at all levels is very deficient and the laws, ordinances, or agreements they approve are mere “patchwork quilts”, that is, poor quality norms.

The increase in the number of political actors and the minimum requirements to form them has not served to strengthen adherence to democracy, since, according to surveys, the number of citizens who claim to belong to a political party is decreasing day by day. But we are also observing two additional worrying phenomena: on the one hand, the multiplication of personalist parties and, on the other hand, the expansion of regional family clans. In other words, a growing absence of political projects and collective programs.

The hypotheses to try to explain this increase of the GSCs by the MOE are mainly three: first, they have more time than the political parties or movements to campaign, since from the delivery of the forms for the collection of signatures (eight months before the elections) they start, in fact, their electoral agitation. Secondly, due to the distrust and bad image of political parties — which, according to the last Invamer survey published in February 2023 have 77% unfavorable and 11% favorable —, many politicians or aspiring politicians prefer to present themselves as independents. Finally, the high number of political parties and movements has led to a profound blurring of party programs and symbols, that is, of their ideological identity.

What to do?

The recent regional elections have once again set off alarm bells about the deep disorder of our electoral and party system, which I would not hesitate to qualify as one of the most deficient in the world. The serious issue is that substandard politics is followed by deficient public administration.

Especially in a country where a true administrative career has not been consolidated and where the political groups that come to power at all levels seek to fill public positions with their followers and sympathizers with total autonomy of their experience and administrative capacity, in addition to paying political favors. According to renowned researchers such as Miguel Ángel Centeno and Agustín Ferrado, the only Latin American countries with autonomous public administration and career civil service are Chile and Costa Rica. In Colombia, nepotism and political protégés prevail, that is to say, loyalty or family ties are privileged over capacity.

Therefore, it is time-critical to reach a great national agreement on the reorganization of the electoral and political party system, as well as the need for a true administrative career at all levels in the country.

*Translated by Janaína Ruviaro da Silva from the original in Spanish.