The recent elections in Colombia ratified a trend that has been manifesting in Latin America since 2018: progressive governments’ return or coming to power. Despite this political change, the economic difficulties that Latin America has been facing since the middle of the last decade are far from being overcome. The trends toward income concentration and increased poverty, which had been reversed during the “pink wave”, have returned, reinforced by the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine. In this framework, regional integration and China’s role in the region are two key challenges.

A “second pink wave”, under the sign of moderation

Since 2018, with the victory of Andrés López Obrador in Mexico, a “new pink wave” has emerged, completed by the coming to power of progressive governments in Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Peru, Ecuador, Honduras, Colombia, and, possibly, Brazil in the near future.

So far, this second cycle shows a difference with respect to the previous experience: without the favorable external conditions of the beginning of the century and under the legacy of a disintegrated productive structure, governments do not seem to face major transforming projects.

Indeed, beyond the poverty reduction and distributive improvements of the 2002-2015 cycle, the modalities of surplus generation, especially the extraction of primary rents or the intensification of low value-added activities, weak in productive chains and technological innovation, remained practically unchanged. There was a partial change in the appropriation of this surplus through improvements in direct and indirect wage income and, to a lesser extent, its destination, since capital flight has increased as a result of the 2008 crisis.

In an external and unfavorable situation, the governments of this second progressive cycle face the double challenge of doing what they have already done — improving income distribution and expanding rights — and, at the same time, doing it differently, and not only having an impact on the appropriation of the surplus but also on its generation.

So far, given the circumstances, economic moderation has prevailed through prudent monetary and fiscal policies, after the spending shock during the pandemic. Changes in the tax system to make it more progressive are on the agenda. Meanwhile, aspirations to modify the productive matrix seem to have been shelved in the face of a commitment to intensify primary extractive activities.

The need for foreign exchange thus conspires against the redefinition of the mechanisms for obtaining these resources. Not only does the intensification of primary extractive activities have the disadvantage of entailing fewer local or regional productive networks than other tasks, but it has also been questioned for its environmental impact. In this trend, the presence of China, the rising power that invests most in them, is becoming more important.

The challenges of integration and China’s potentiality

In this perspective opened up by progressive governments, there is a renewed commitment to integration. The recreation of the coordination bodies that were set aside during the period of conservative governments appears as a first response—also, the novelty of Mexico as a potential centerpiece. However, the lack of coordination between countries still prevails, an aspect that was evident in the strategies to face the pandemic.

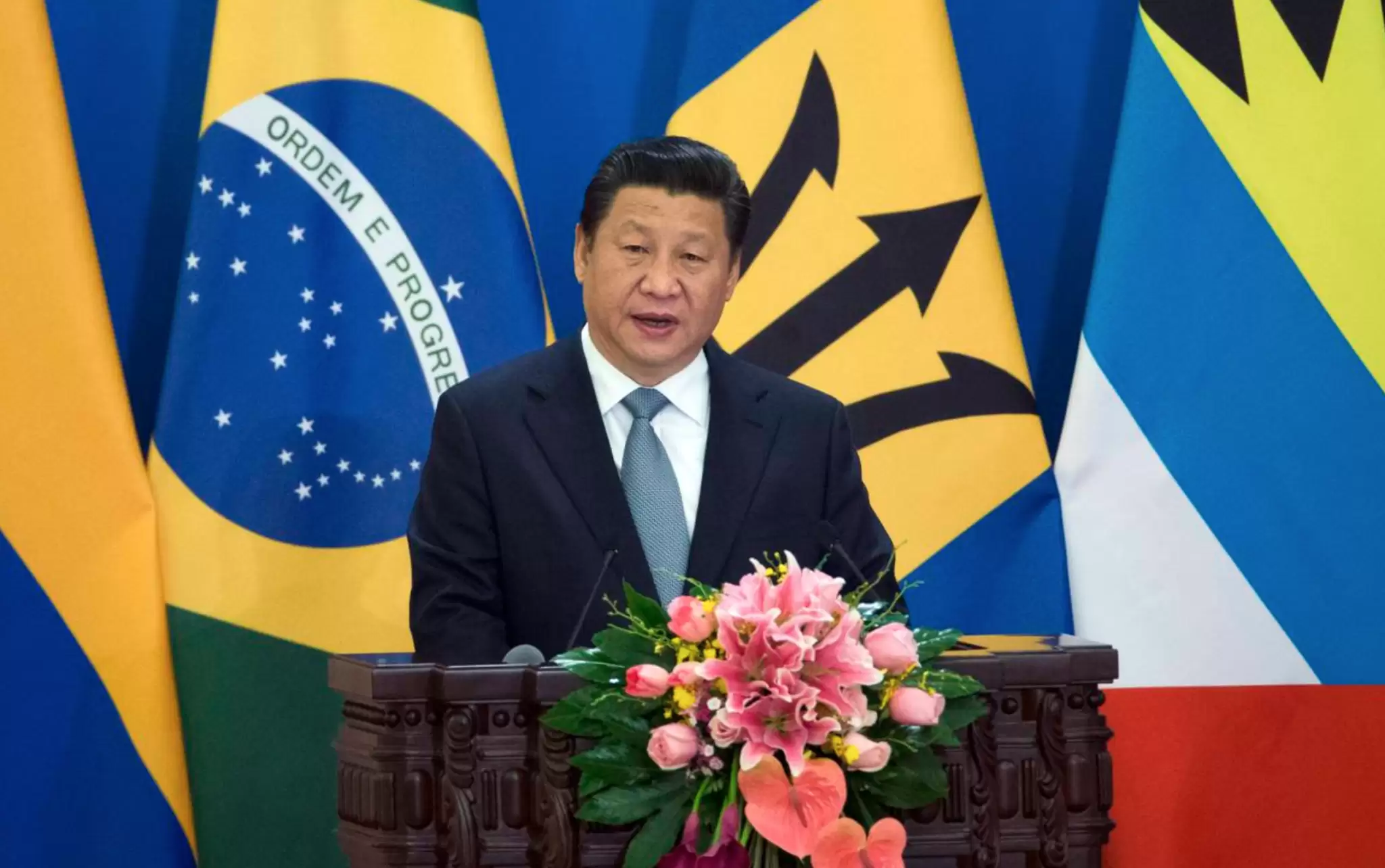

The challenge of integration is linked, geopolitically, in a context in which China and its capacity for investment, financing, and commercial deployment mark a new scenario. Beijing’s Belt and Road initiative has brought together 21 Latin American countries. However, this possibility arises at a time when China itself has decided not to grant loans to the region since 2020 in view of its own economic slowdown and the growing rivalry with the United States.

While the Belt and Road Initiative could open up opportunities for infrastructure development in the region, it requires a coordinated strategy in which regional complementarities are enhanced. Once again, the political scenario could be aligned. Will there be a common strategy this time?

* This text was originally published on the REDCAEM website.

Translated from Spanish by Janaína Ruviaro da Silva