While the long-term ramifications of the war in Eurasia are still uncertain, there is some consensus among analysts that a new international configuration will emerge precisely because of this problem.

If the war does not become widespread, diplomacy and peace negotiations will prevail over brute force. More likely, the new international scenario will be characterized by greater multilateralism through the strengthening of alternative geopolitical blocs, in addition to those traditionally predominant in the West.

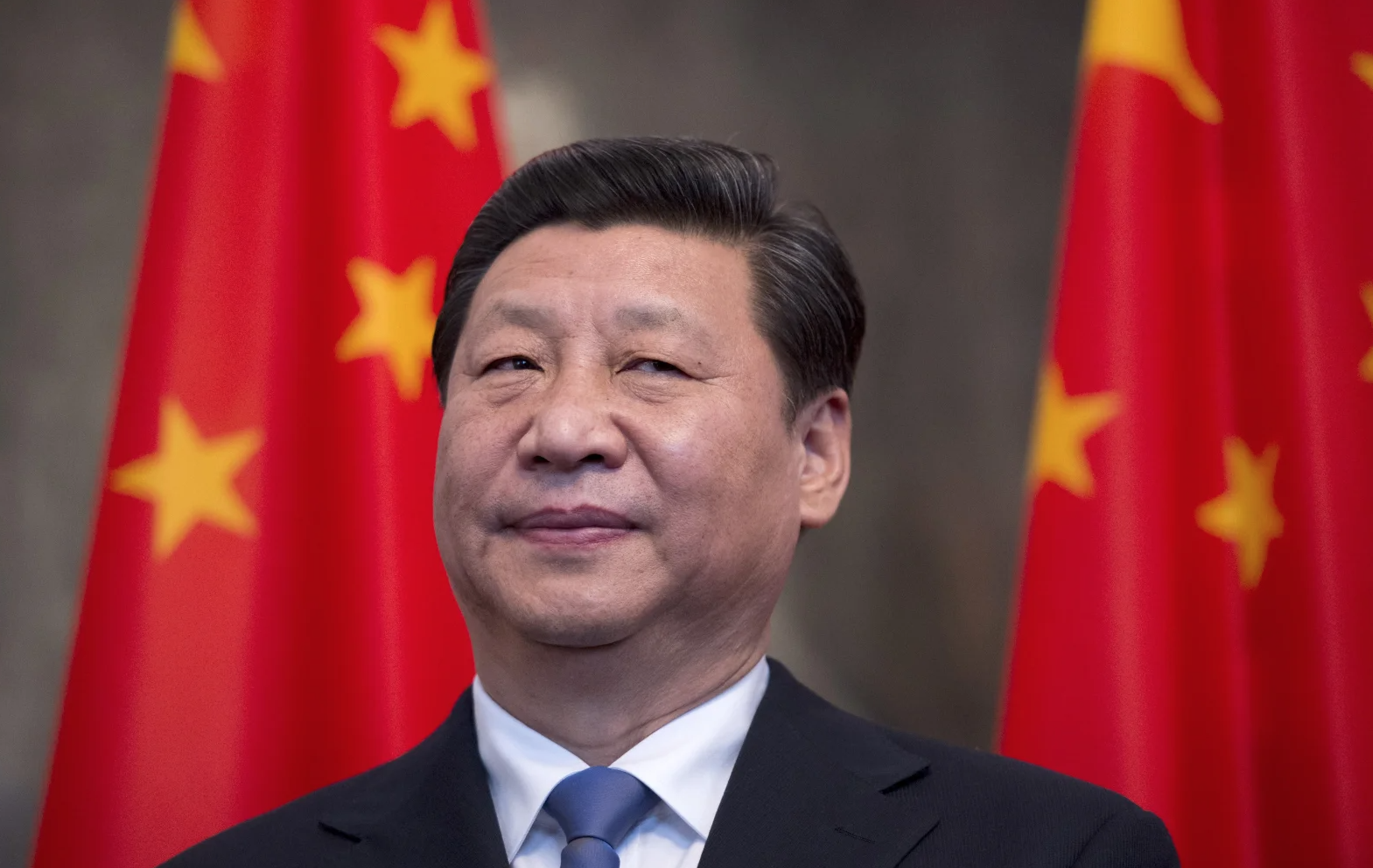

If this situation occurs, it will be compatible with the age-old guidelines of China’s foreign policy when its pillars were set by Premier Zhou Enlai, which have proved particularly relevant since the events of the late 1960s that culminated in Richard Nixon’s historic visit to China in February 1972. This was one of the most important diplomatic events of the last century, which celebrated its 50th anniversary in February of this year.

It is true that the world has changed a lot since that event, but China continues to follow (as part of its foreign policy) the fundamentals of those guidelines. Among them are respect for the economic sovereignty of peoples and their right to decide autonomously on their destinies and their political system, without imposing political regimes by force against the will and cultural characteristics of these peoples.

There is also the predominance of peaceful and diplomatic negotiations over the use of military force for the solution of international conflicts. In terms of trade relations between countries, Chinese foreign policy typically supports the consistent defense of multilateralism through the construction of diverse and sovereign economic blocs, including in the Global South through the deepening of “win-win relations” when it comes to foreign trade.

The possibility of realizing this future scenario through the continued growth of the Chinese economy and the implementation of its guidelines of mutual economic gains and respect for the sovereignty of peoples represents a series of challenges for Latin American countries.

These challenges come from the need to optimize the opportunities that the emergence of new economic blocs and the growth of multilateralism represent, without implying exclusive and unilateral adhesion to any of them but maintaining good relations with several countries that bring economic stimuli to the region.

Thus, the recent trade agreements between Argentina and China are very promising, with the former joining the Belt and Road initiative, which opens the way for BRICS growth, especially if these agreements generate a new cycle of continuous economic progress and greater inclusion in the continent.

The case of Uruguay and the formal start of negotiations for a Free Trade Agreement (FTA) between this country and China is another example of progress in Sino-Latin American relations.

Although Brazil has not yet advanced as far as Argentina or Uruguay (in terms of trade and political agreements) with China (although China is already its largest trading partner), there are several important initiatives underway in the country that point to a promising future for political and cultural development and trade between the two countries (despite some recent minor incidents, which could be overcome in the near future).

The current construction of the bridge between Salvador and Itaparica, two of the main economic and tourist centers in northeastern Brazil, is of particular note, as it is currently its largest infrastructure project. This case is an excellent example of the realization of “win-win relationships” in that both partners in the relationship benefit from the investments and works scheduled to begin soon.

On the one hand, Brazilians win, since the historical demands of the population to improve the quality of travel services between the two locations, a long-standing bottleneck in trade and tourism flows in the region, are being met. On the other hand, the Chinese win, as they get visibility for their infrastructure-building business in Latin America and expand its presence in the region. They also win by spreading a more advanced model of economic management around the world that is based on mutual gains between countries, sustainable development, and respect for the environment. In doing so, it also adds Brazil to other countries already benefiting from infrastructure investments that will create positive externalities in their respective economies, as well as benefits for Chinese companies and entrepreneurs.

It is evident that an undertaking of this magnitude may go against well-established interests, especially those that were favored by the previous political situation of chronic deficit in infrastructure investment with which, however, they obtained extraordinary and disproportionate profits. All the while they left population with means of transportation that were archaic. Hence the need for a constant and daily effort on the part of the partners involved in this project to clarify the positive impacts of the work in the region to the public. This will greatly help the local population as a whole.

Finally, it is possible to affirm that the intensification of diplomatic and commercial ties between Brazil and China in the near future, based on the principles of mutual respect for both sovereignty and cultural specificities of the peoples and on “win-win relations”, can serve as a promising counterexample to the future prospects offered by those who, in the 21st century, wish to restore the archaic mentality of “cold war” and “clash of civilizations.” These mentalities, without a doubt, are bringing the world to the close of a war between superpowers.

This situation only favors the big companies of the military-technological complex and their sympathizers, the politicians financed by these companies, but they exclude from their list of priorities the demands of the working population and local entrepreneurs.

* This text was originally published on the REDCAEM website.

Translated from Spanish by Alek Langford