electorate’s emotional obedience than on institutional balance. The political map did not merely change color; it changed logic. America is turning once again, but it does so on increasingly fragile ground, eroded by civic disenchantment, structural insecurity, and the inability of political systems to produce certainties.

South America in tension

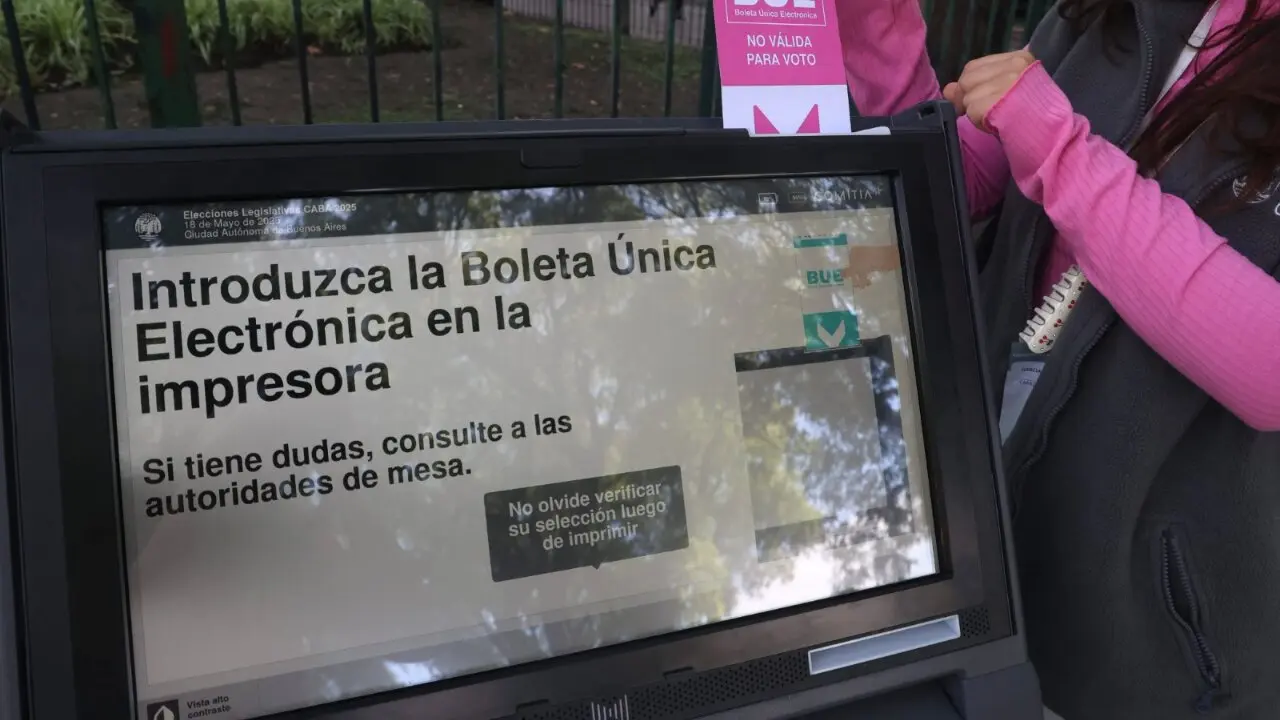

South America was the most visible stage of this transformation. In Argentina, Javier Milei moved through the second year of his singular liberal-libertarian experiment with a deep economic adjustment that, while beginning to contain inflation, failed to ease the daily burden on the most vulnerable sectors. The country remains trapped between a government that sees itself as the bearer of a “refoundational” mission—willing to break with decades of statist practices—and a weary society demanding tangible results beyond speeches about cultural revolution or economic freedom. This is not merely about the success or failure of an economic program; what is at stake is the very possibility that an anti-system project can become a democratically sustainable alternative.

Chile confirmed this regional trend. The electoral victory of José Antonio Kast symbolized the return of a hard right to power, backed by a decisive territorial vote. However, that triumph did not translate into unrestrained governing capacity: the new president arrived with limited parliamentary strength, forcing him to operate within an adverse and highly fragmented Congress. The Chilean case once again shows that electoral legitimacy does not always guarantee governability, and that the continent is moving toward a model in which presidential popularity clashes with legislative counterweights that weaken it from day one. Bolivia offered the most symbolic rupture: after two decades of MAS hegemony, a center-right government came to power and attempted to dismantle the distributive pillars that had defined the country since the beginning of the century. The social reaction was immediate—strikes, protests, and a political conflict that returned the country to instability. Brazil, for its part, opted for continuity. Lula da Silva announced his intention to run again, feeding a regional paradox: the continent demands renewal, yet many of its central figures continue to rely on leaderships from the recent past.

Security as a new social contract

Central America experienced a different process: there, the dispute was not ideological but institutional. El Salvador deepened its plebiscitary model of total security, with a state that expands from prisons into all areas of public administration. In Nicaragua, political repression continued with the same intensity, and democracy ceased to be a horizon and became a memory. Guatemala attempted to advance an anti-corruption agenda under the constant threat of political and judicial networks seeking to block any structural reform. Central America appears to have resigned liberal democracy in exchange for strong leaderships, and what is troubling is that this shift enjoys significant popular approval.

Meanwhile, Mexico and Ecuador represented the Latin American conflict between structural violence and democratic legitimacy. In Mexico, the first phase of Claudia Sheinbaum’s government was marked by a strategic adjustment in security policy: the participation of the armed forces as a central element of territorial control was maintained, but the civilian component in prevention, intelligence, and institutional coordination was strengthened. This approach, together with a stable economic environment and the strength of the dollar, helped sustain high levels of presidential approval toward the end of the year. In parallel, the new Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation began its work amid high expectations and intense public scrutiny. Nevertheless, between September and December the Court led by Hugo Aguilar Ortiz managed to consolidate an image of institutional autonomy: it operated with its own criteria, kept distance from political pressures, and reaffirmed its ability to guide the judicial agenda independently. Its functioning reduced initial fears about judicial redesign and strengthened the perception of balance among branches of government.

Ecuador followed an opposite yet similar path: Daniel Noboa consolidated his mandate on the promise of confronting organized crime head-on. His reelection confirmed that citizens no longer vote solely for economic or ideological projects, but for personal protection. Security ceased to be a sectoral policy and became the very essence of the social contract.

In North America, Donald Trump’s return altered the hemispheric balance. The United States reinstated an agenda marked by migration pressure, hardened borders, and a more confrontational stance toward authoritarian regimes. The Caribbean, for its part, continued to drag along its most severe humanitarian crisis: Haiti remained mired in institutional collapse, becoming a stark reminder that the failed state is no longer an academic category but a lived experience.

Exhausted democracies: competitive elections and punitive drift

Viewed as a whole, the continent in 2025 presents three unsettling conclusions. The first is that electoral democracy continues to operate, but liberal democracy is eroding. There are competitive elections, but decreasing acceptance of the limits that sustain the system. The second is that discontent no longer fuels progressive projects of social reform, but punitive leaderships that promise order before a future. The third is that the growing obsession with security has displaced historic discussions about inequality, integration, or development; today the continent does not debate how to grow, but how to survive.

American democracies remain alive, but they are exhausted. Governments change, ideologies rotate, borders are redrawn, yet uncertainty does not clear. America, in 2025, reconfigured its political map without managing to answer the essential question: are we moving toward a stronger democracy, or traveling toward an order in which fear replaces citizenship? The year closed without a clear answer, though it left a precise warning: fatigued societies do not always choose what is best; they choose what is immediate. And what is immediate today is called security.