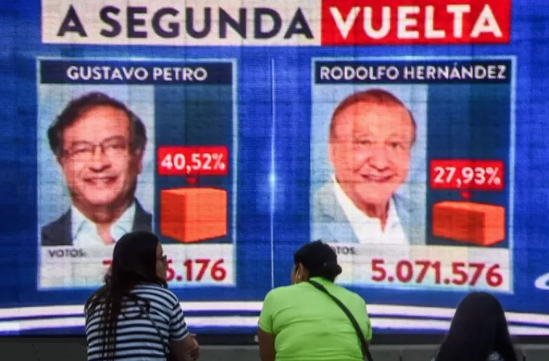

One: The Colombian left, led by Gustavo Petro, has obtained the best result in its history in the first electoral round. So much so, that in a context of high turnout for what Colombia represents (55%), the Historical Pact, which brings together all the progressive forces of the country, has obtained more than eight and a half million votes. A figure that even surpasses the result of the second electoral round of the 2018 presidential elections and consolidates the maxim that the former mayor of Bogotá is the candidate to beat.

Two: Uribism consummates its particular process of decadence. Since 2010, after two consecutive presidencies of Álvaro Uribe, the candidate he nominated was guaranteed to be present in the second electoral round. However, for years, the image of the maximum defender of the Democratic Security Policy has been losing ground. The messianic image of the past has given way to a figure blurred by excess, dogmatism, and manipulation. To this must be added the discredit of Iván Duque, with no government agenda in these four years and with favorability indexes that only a few months ago barely reached 25%.

Three: Sergio Fajardo is the great defeated. Only four years ago he was on the verge of going to the second electoral round, being finally beaten, by a slim margin, by Gustavo Petro. Had he succeeded, given the electoral volatility in his favor, by occupying the space of ideological moderatism, he would have possibly reached the presidency of Colombia. However, his candidacy emerged from a deeply fractured coalition of names, with confronting personalities, and which has developed a gray campaign, without great proposals, with lukewarm participation in the debates, as if at no time Fajardo had believed himself capable of getting into the second round.

Four: Rodolfo Hernández is a great surprise. His voting intention in the last months has been more or less stable, between 10% and 12%. His condition of outsider and defender of anti-politics against elitist traditionalism enjoys a remarkable audience. A better than expected breeding ground for a candidate who is a sort of Donald Trump à la bumanguesa (related to the Bucaramanga city), who lacks government programming, who maintains a simplistic discourse at the service of demagogy, and whose presence is in social networks – especially Twitter and TikTok.

Fifth: The liberation that the Peace Agreement has meant for the left is evident. For decades, the survival of the armed conflict meant that a large part of the political-partisan scaffolding gravitated around the cleavage that fed the violence. Thus, with the demobilization of the FARC-EP, the visibility and politicization of other aspects of the public agenda, such as education, health, housing, or employment, have gained in importance. This has stirred up Colombian society, motivating broad scenarios of mobilization and protest, and building the viability, as an alternative, of a democratic left to lead the country.

Sixth: Colombian political culture is a sum of ingredients that, in one way or another, just as they allow us to understand the rise and popularity of Gustavo Petro, can help us to understand that someone like Hernandez sneaks into the second round. Even in many places in Colombia, a parochial and conservative political culture prevails, which the traditionalist elitism has not known nor wanted to understand. Its excesses in the appropriation of the State assets, and the image of continuous plundering, resulting in corruption as endemic as clientelist, provide an ideal scenario for the anti-establishment and anti-corruption discourse that Hernández demagogically raises.

Seventh: The situation of the second round plays in favor of Hernández. Uribism and Federico Gutiérrez himself have already expressed their support for the candidacy of the former mayor of Bucaramanga. All this, without negotiations or previous requests, knowing that any possibility better than Petro is the only desirable one for their interests. Uribism, the party machinery of the Liberal Party, the Conservative Party, or Radical Change Party, with great territorial anchorage, will go in favor of Hernández, as will the majority of a media spectrum that continues to consider Petro the personification of Bolivarism in Colombia.

Eighth: Although for Gustavo Petro the candidate that best suited his interests was Federico Gutiérrez, all is not lost. Of course, he has to avoid the discourse that figures such as Hernández motivate, since his interventions arouse impulsion, improvisation, scarce viability, and easy insult. In the face of anti-democratic demagogy, the weapons must be others, as evidenced by the campaigns in the continent, from the United States to Brazil, passing through El Salvador. It will be important to attract the center vote, the vote not mobilized in the first round, and to prioritize the geographical enclaves, mostly peripheral, which together with Bogotá have supported the progressive and peace agenda, since 2016.

Nine: In the coming days it is to be expected that former presidents César Gaviria, Andrés Pastrana and Álvaro Uribe will position themselves with Rodolfo Hernández. Seeing the remaining sum embodied by Iván Duque, his presence in the campaign, possibly, will be more crafty than in the first round, where he clearly positioned himself on Gutiérrez’s side. Among the former presidents, Petro has the assured support of Ernesto Samper, but it remains to be seen what Juan Manuel Santos does. It is possible that an eventual endorsement on his part, added to that of other figures, such as Sergio Fajardo, may qualify Petro’s projection on part of the collective imagination and attract the moderate voter who, initially, in other circumstances, would never vote for Petro.

Ten: Of course, Colombia has a lot at stake in these elections, and it is not a recurring maxim. After four years of inaction, misgovernment, and involution in most of the social and security indicators, the arrival of Hernandez to the presidency must be understood as a threat to institutionality. Petro is the only one who proposes a programmatic agenda coherent with the challenges of a Colombia that demands, among many other issues, more public spending, better redistribution of resources and opportunities, greater institutional capacities in the territory, and the return to a path of peace, completely blurred after the disastrous outgoing presidency of Iván Duque.

Translated from Spanish by Janaína Ruviaro da Silva