In Latin America, democratic demands depend on who is in government. Carl Schmitt warned us more than half a century ago of this way of understanding politics. Creating an antithesis, whether material or imaginary, to justify the fierce struggle for power and prevent “the other” from winning and overcoming the “unique and sacrosanct intentions” of one of the sides. The good guy versus the bad guy, the empire versus the rebel alliance, the avengers versus Thanos. From time to time, the sides present us with their chosen one, an anointed one by the “stars” -or a political rally- who with an iron hand, trumpet voice and great eloquence envelops the citizens offering them “the definitive victory” over the enemies, the anti-patriots or oligarchs.

The friend-enemy dichotomy

If “the good guys” must bypass the institutions, it doesn’t matter! It doesn’t matter if it involves coups d’état, eliminating the rule of law, changing state institutions by force, attacking basic principles, turning a blind eye to attacks on the separation of powers, ignoring the legislative branch as a counterweight, or calling democratic discussion a “blockade” when “the good guys” cannot impose their agenda.

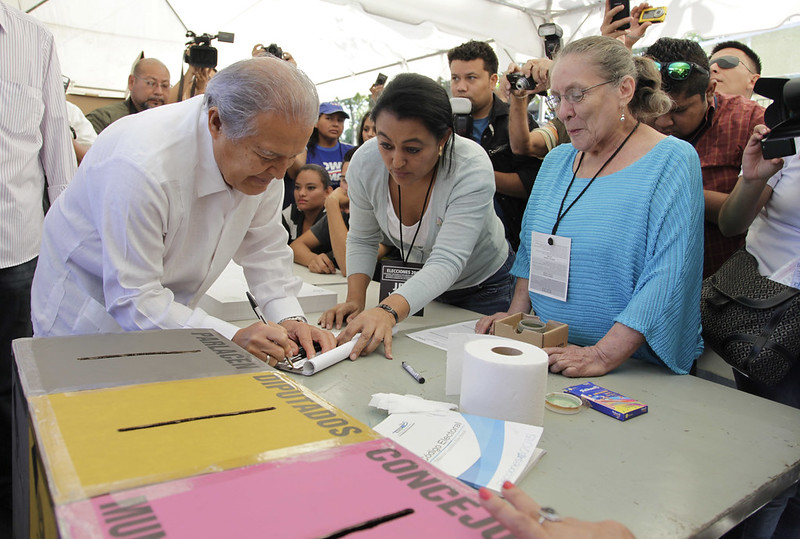

Examples abound in Latin America, both on the left as well as on the right. In El Salvador, the legislative majority of Nayib Bukele, the most popular president in the region, illegally dismissed the members of the Supreme Court of Justice, taking control of the constitutional chamber. Months later, the Supreme Court authorized the president to seek reelection despite its unconstitutionality.

In Ecuador, former president Correa used popular consultations to give legitimacy to his pretensions, claiming that his political project would save Ecuador from the “claws of the pelucones” and would allow “the great fatherland” to reach its “second and definitive independence”. Paradoxically, current president Lasso, an opponent of the former president, announced the possibility of calling for a popular consultation to unblock an alleged “blockage” of the National Assembly to his labor and tax reform bills. But for his followers this does not matter, their leader can pass over the institutions -as Correa did without being a tyrant like Correa- since he belongs to the “side of the good guys”.

Institutionality? It is the first thing that should be demanded from the opponent. But we must not abuse it either, least to become a brake “to the country’s project”. And if it becomes an obstacle, it should to be ignored, modified and if necessary eliminated. It happened with Fujimori in the 1992 coup d’état, with Correa in 2011, with Uribe in 2010 and Evo Morales in 2019, these last trying to go for reelection bypassing all the rules.

What about democratic values?

The political culture in this part of the world lacks democratic values. Dialogue is confused with weakness, respect for the law is synonymous with candor, and tolerance is practically intolerable. Unfortunately, we have a political culture that melts in the face of demagogy and we incessantly seek messiahs to “save the people” -even if they are authoritarian- as long as they are part of “the good guys”. Democracy cannot be possible as long as “the other” is in charge.

I do not intend to make an analysis and even less to refute the studies on populism carried out by great social scientists such as Carlos de la Torre, Loris Zanatta, Margaret Canovan, María Antonia Muñoz or Ernesto Laclau. But it is worthwhile to analyze and criticize not only the political actors, but there must also be a strong criticism from and towards the citizens.

We often blame politicians for the stagnation of the country and we blame them for the shortcomings of democracy, but when have we citizens ever stood in front of the mirror to examine our own miseries, the same miseries that weaken democracy and institutions? To what extent is the “government of the people”, which neither cares nor understands democracy, not a chimera? Until when will we respect democracy, as long as it suits us? Could it be that we Latin Americans are the worst threat to our own democracy? To change this, it is imperative to change the political culture of our countries. But who knows, nobody cares too much.

Autor

student at the University of Salamanca (Spain). Master in Interantional Relations from the Instituto de Altos Estudios Nacionales (Ecuador) and in Political Science by the Univ. of Salamanca.